Jihadist attacks have sent sporadic tremors through European societies for over 25 years. The ferocity of terrorist acts has also stunned Muslim communities. Now social networking provides a platform for dissenting Islamic voices critical of cultural and religious norms that fail to counter violent radicalisation or serve to indulge it.

Since 2015, attacks by militant jihadists have repeatedly plunged European cities into mourning while sending shockwaves through Muslim minority communities. The full impact and consequences of the ‘ISIS tragedy’ have yet to be revealed. In French-speaking countries, the most significant reactions include the emergence and affirmation of Islamic voices deemed ‘reformist’ or ‘progressive’,1 a recent shift towards practical forms of community organization extending beyond social networks2, and an increasingly liberalized approach giving legitimacy to ‘talking Islam’. All these are challenging more traditional forms of community leadership.3

In parallel, conservative discourses have faced growing criticism from within Muslim communities for their inability to produce an effective counter-discourse to ISIS. This is true of the Salafist4 movement in Sunni Islam for example, the Muslim Brotherhood,5 or of groups with ties to the institutionalised Islams of countries where they originated.

Traditionalist colloquies are accused of indulging Islamist theological and normative foundations and failing to distance themselves from, let alone criticize, the theological and legal frame of reference they implicitly share.6

However, the increasingly radical and uninhibited questioning of religious authority remains mostly invisible, and the discursive hegemony of these conservative currents is far from being relegated to a footnote in the history of ideologies. Yet despite this, since 2015, critical voices have been making themselves heard in ever greater numbers. They feature particularly on social media platforms like Facebook which amplify personal reflections and mobilize a range of discursive techniques that openly interrogate conservative thinking and sometimes lead to radical existential questioning.

Photo by European Parliament from Flickr

A paradigm shift

Today, it is important to look beyond media figureheads, like Ghaleb Bencheikh, Tareq Oubrou or Mohamed Bajrafil, to find voices under the media radar actively encouraging Muslims to reappropriate their agency and critical awareness. This has become possible thanks to the confidence these authors gain from the interpersonal relationships and the sense of kinship that characterize virtual micro-communities that are founded on shared intentions and interests.

Social networks enable close and direct connection with dissenting voices. Furthermore, online conversations – whether public or private – seem to have much greater impact on digital ‘friends’ and contacts than traditional spaces for intellectual discourse such as books, conferences, or predominantly non-interactive media. Beyond the concept of connective intelligence developed by philosopher Vincent Cespédès,7 which describes it as circulating, co-creative and open source, these voices represent – for their ‘friends’ – discourses that are disruptive, yet embodied by individuals and their behavioural practices.

For networking participants, this personal link strengthens emotional bonds and the desire to draw inspiration from the connection, for themselves and their own practice. These voices are more powerful and potentially influential than more conventional intellectual figures.

Clearly, I am not attempting to defend a naively optimistic view of the potential of social media. Nor would I wish to pit social media against more traditional channels for sharing knowledge and encouraging public discourse. I prefer rather to emphasize the compatibility between the two. My focus here is on the role of actors who appropriate and draw inspiration from the ideas of prominent figures, and who then go on to present their own thoughts, comments, conclusions and practices to their digital ‘friends’. This is equally important in the context of a fundamental paradigm shift in how individuals and groups relate to Islamic norms.

Recovering agency

John Dewey’s theory of the ‘public’8 seems relevant in this context. It provides interesting insight into how these voices enable a specific group (in this case, French-speaking Muslims) to:

- Become aware of the impact conservative discourse has on their private and public lives;

- Constitute an audience – individually or as a group – through self-reflection initiated by such voices;

- Reshape their lifestyles and beliefs while protecting themselves from practices and discourses that may deprive them of their capacity to think and act, or damage their private, professional, social and civic lives;

- ‘Restore the possibility of a private life directed towards goals that are motivated by individuality being constructed and so independent of any harm suffered’. 9

Although we are not talking here about constituting a ‘citizen’ public as Dewey understood it, these voices nevertheless bring very disconnected ‘publics’ together sufficiently to contribute to the emergence of a quasi-political life in ‘communities’ based on shared orientation, practice and increasingly interlinked knowledge.

For online dissenters, fracturing hegemonic Islamic discourse is about taking back control over their lives and destinies, and reconnecting with the wider social fabric or indeed society itself. They can then become active agents working towards the common good. By emerging from the ‘Islamic bubble’, they may help eliminate an almost permanent sense of dissonance with the social environment.

Photo by ittmust from Flickr

Defying orthodoxy

The ways in which these voices mobilize different discursive regimes deserve to be analysed separately. They include irony, religious studies, Islamic studies, eroticism, traditional Islamic scholarship, spirituality, sociology, the history of social imaginaries and so on.

Each voice has its own method of challenging totalizing, if not totalitarian, Islamic discourse, and eroding the consent10 of Muslims. In the absence of coercive mechanisms, these are the forms of defiance on which dissent relies. Meanwhile, the only forces ensuring consent to conservative Islamic norms are fear of hell or peer pressure, and the individual, fragmented nature of any challenge to authority.

In highly secularized, liberal societies, numerous philosophies compete in markets peddling discourse on happiness and the hereafter. The forces that uphold consent are significantly weaker here than in societies where views on such subjects are broadly homogeneous, and where the authorities maintain a range of institutionalized coercive tools at their disposal. These may include religious or moral policing, as well as other systems of social control.

The following four examples offer an illustration of the innovative discourse described above.

Tradition against itself

Sâlik al-Hani is reportedly a student of Islamic studies, with just under four hundred ‘friends’ [at the time of this writing in 2020 – upon this publishing in English in 2021 it’s above a thousand contacts – ed.]. His modest reach does not diminish the technical quality of his posts, however. Using Arabic texts by traditional ulemas to support his arguments, he has given himself the mission of contesting what he calls ‘sahihology’: the study of the authenticity of hadiths (sayings of Muhammad) or the doctrine of abrogating and abrogated verses in the Quran.11

He does so by pointing out contradictions, incoherencies, and the absurd corollaries of the ulemas’ positions. He brings up key points often neglected in the discourse of Islamic clerics, possibly because they have a poor knowledge of their tradition or because they prefer to avoid drawing attention to inconsistencies and unintelligibility in the sacred teaching to which they have dedicated their lives.

Sufism as a reconnection with a scholarly tradition

Anne-Sophie Monsinay12 is a teacher with more than two thousand ‘friends’, who openly adheres to Sufism. She regularly cites passages from the great Sufi masters, including the Persian medieval poet Rūmī13, the mystic-philosopher Ibn al-‘Arabī 14 and the Persian poet, mystic and teacher Rūzbihān Baqlī .15 She also encourages forms of theological and metaphysical reflection largely absent in the discourse of Islamic clerics.

Overstepping questions about identity, victimhood or the politics of Islam, Monsinay appeals to an Islam of the heart, with a focus on introspection and mystical elevation, and challenges the superficial application of orthopraxy or ‘correct conduct’. She is a founder and imam of the inclusive Simorgh mosque.

Weapons of mass deconstruction: irony and humour

Saïd Derouiche is a psychological sciences graduate and practitioner of Ericksonian hypnosis.16 He uses examples that are as implausible as they are true to highlight the profound psychological impact of some rigorist Islamic practices or alienating beliefs, particularly those related to female sexuality.17 He also employs parody18 to reveal the ethical incoherencies of a celebrated Islamic preacher and his disciples, showing how they justify their claims by interpreting theological texts in a specific way.

Romanticism of the body as the subversion of the Islamic patriarchy

Sarah Hatimi, a student from Toulouse whose relationship with Islam is implicit, describes her encounters and love affairs to an audience of almost a thousand ‘friends’. Her body, with its desires and emotions is the chief protagonist of her adventures.

Her texts, photos and stylized selfies explode religious taboos and conservative representations of sexual desire, particularly a woman’s desire, offering a frank but never vulgar portrayal of a fully assumed feminine subjectivity. Her readers appear to be unaccustomed to seeing such outspokenness in the prudish world of standard Islamic discourse.19

These four are just some of many voices contributing to the emergence of a distanced, even subversive approach to conventional Islamic discourses. They attract audiences that are increasingly wider, more attentive and more structured.

In challenging the mainstream discourse, they participate in the creation of spaces where people can develop new relationships with Islam as a religion, a spiritual discipline, a normative system, or a source of meaning for Muslims seeking to restore enchantment to their daily lives, while acknowledging or wholly accepting their full assimilation into secularized European societies.

Translated and edited by Cadenza Academic Translations. Translator: Isabelle Chaize, Editor: Faye Winsor, Senior editor: Mark Mellor.

This article was originally published in La Revue Nouvelle (1/2020) as part of a special issue on Islam in Belgium.

For example: Ghaleb Bencheikh (president of the Foundation for Islam in France [Fondation de l’Islam de France]), Mohamed Bajrajil (essayist and imam), Kahina Bahloul (Islamic studies expert and imam), Razika Adnani (Islamic studies expert), Omero Marongiu-Perria (sociologist and essayist), Seydi Diamil Niane (Islamic studies expert and essayist), Tareq Oubrou (imam), Eva Janadin (academic and imam), Hicham Abdelgawad (researcher and essayist), Islam b. Ahmad (theologian).

Cédric Baylocq, 'L’Islam réformiste en France: des débats numériques à l’espace socio-religieux' [Reformist Islam in France: From digital debates to a socio-religious space], Oasis, 16 July 2019, https://www.oasiscenter.eu/fr/islam-reformiste-en-france-debats-et-projets

Michaël Privot,“Réflexions sur la ‘légitimité’ islamique dans l’espace francophone européen” [Reflections on Islamic legitimacy in the French-speaking European area], Les cahiers de l’Islam, 25 February 2016, https://bit.ly/2E4PLoC

Samir Amghar, Le salafisme aujourd’hui. Mouvements sectaires en Occident [Salafism Today: Sectarian Movements in the West], Michalon, 2011.

Brigitte Maréchal, Les Frères musulmans en Europe: racines et discours [The Muslim Brotherhood in Europe: Roots and Discourse], Presses Universitaires de France, 2009.

Omer Marongiu-Perria, Rouvrir les portes de l’islam [Reopening the Doors of Islam], Atlande, 2017 ; Michaël Privot,“Daesh: normativité islamique et éthique contemporaine” [Islamic normativity and contemporary ethics], 2015, https://bit.ly/343Zwhj

Vincent Cespédès, Oser la jeunesse [Let Youth Dare], Flammarion, 2015.

Joëlle Zask, Introduction à John Dewey [Introduction to John Dewey], Editions La Découverte, 2015, 91-110.

Ibid., 101.

Hannah Arendt, On Violence, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing, 1970, 63.

Abrogating text: Nāsikh. Abrogated text: Mansūkh. See: John Burton, The Sources of Islamic Law: Islamic Theories of Abrogation, Edinburgh University Press, 1990.

Monsinay has now transferred her work to a new official group with over 10,000 members: Voix d’un islam éclairé | Mosquée Simorgh

Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, b. 1207 Balkh (now Afghanistan), d. 1273, Konya (now Turkey).

Ibn al-‘Arabī, b. 1165 Murcia (Spain), d. 1240 Damascus (Syria).

Rūzbihān Baqlī

Jacques-Antoine Malarewicz and Jean Godin, Milton H. Erikson. De l’hypnose clinique à la psychothérapie stratégique [Milton H. Erikson: From Clinical Hypnosis to Strategic Psychotherapy], 7th edition, ESF éditeur, 2016.

See: Said Derouiche, #ÇaNaRienÀvoirAvecLislam [This has nothing to do with Islam]

Malarewicz and Godin, 2016

Cheikh ‘Abd Arazzaq Ibn ‘Abd Al Muhsin Al-Badr, Honneur et dignité de la femme en Islam [The Honour and Dignity of Women in Islam], Editions Ibn Badis, 2018

Published 11 June 2021

Original in English

Translated by

Cadenza Academic Translations, Faye Winsor, Isabelle Chaize, Mark Mellor

Published in

In collaboration with

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Can Tunisia’s Islamist party Ennahdha secure the gains of the 2011 uprising and adapt itself to secular democracy? The coalition has been praised for its progressiveness as its new constitution enshrined sexual equality, omitted Sharia law, and maintained the separation between ‘mosque and state’. Leftists, however, fear that these are ‘fig leaf’ measures.

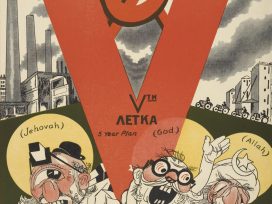

Hammer, sickle, crucifix?

Why 20th-century communists couldn’t decide if they wanted to befriend the religious or blow up their churches

It is true that the Stalinist state treated clerics militantly. Communists, however, were never unified in their approaches to religion or its institutions. Some of them promoted patience and persuasion, others even allied with believers, sometimes despite the fierce rejection of the Catholic church.