The surprise victory of the communist party in the municipal elections in Graz last September has earned the Austrian city the nickname Leningraz – and not in an affectionate sense. But, as Ciril Oberstar writes in Slovenian journal Dialogi, it was not ideology that brought the communists victory over the conservative ÖVP but years of hard, uncompromising activism.

By tackling the practical problems of the city population, from substandard accommodation, housing shortages and public health to traffic regulations, rubbish collection and accessibility of public space, the communist party has gained support across a wide section of the population. ‘In Graz, too, capitalism has been an abject failure with regard to the provision of basic living conditions.’

A similar confluence of city officials and capital can be observed in Ljubljana and Zagreb, Oberstar comments. Here, too, investment-oriented construction is given priority. ‘The steel and concrete of large new buildings are mainly dust in the eyes of city dwellers, as they do not serve their needs,’ writes Oberstar.

In an interview with Meta Kordiš, Matic Primc outlines an alternative: municipal participatory budgeting. Thirty-two municipalities in Slovenia currently use the pilot model developed and adapted by Primc. The method, he says, can solve what can still be solved in our environment and society. Preserving the planet for future generations starts in the local community.

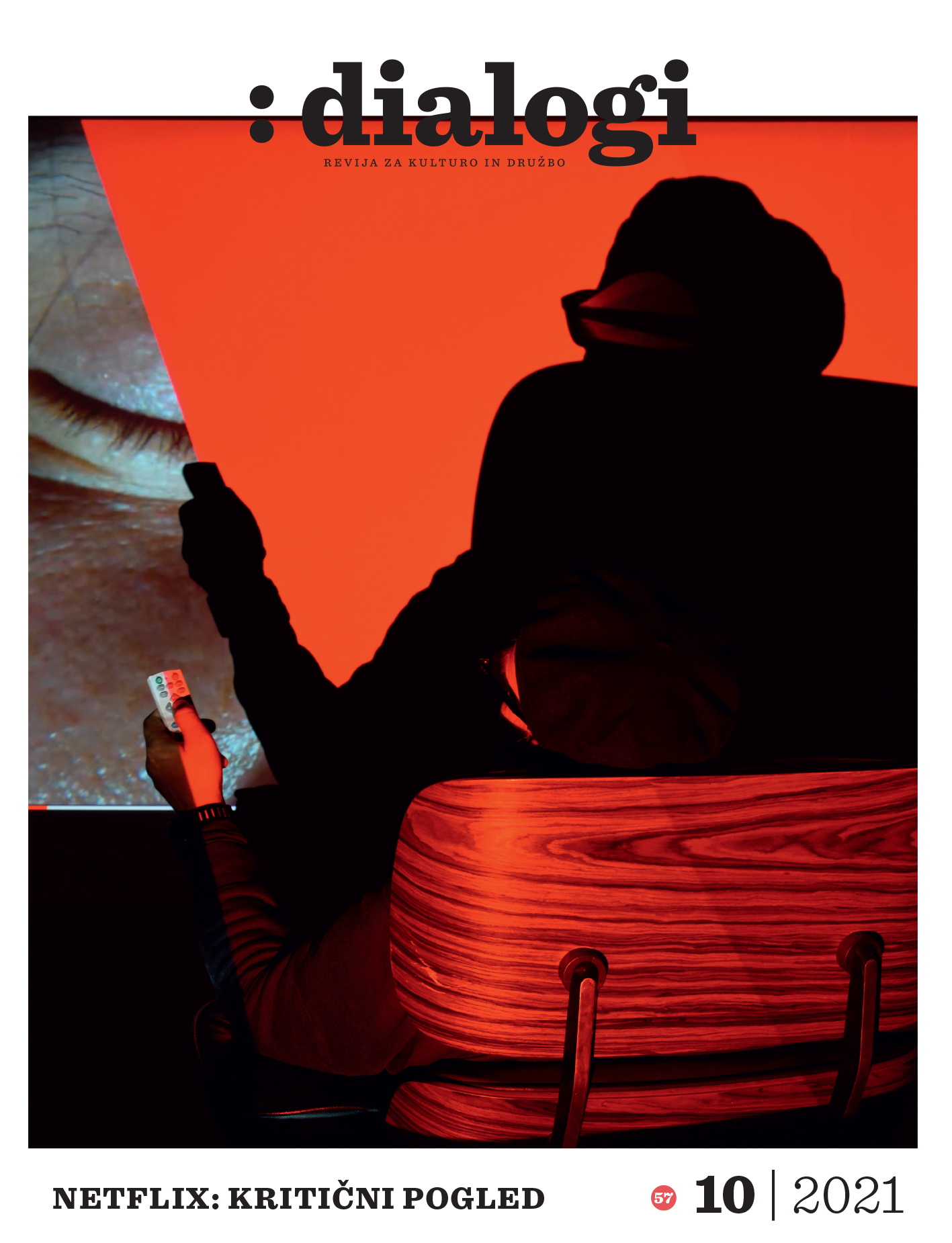

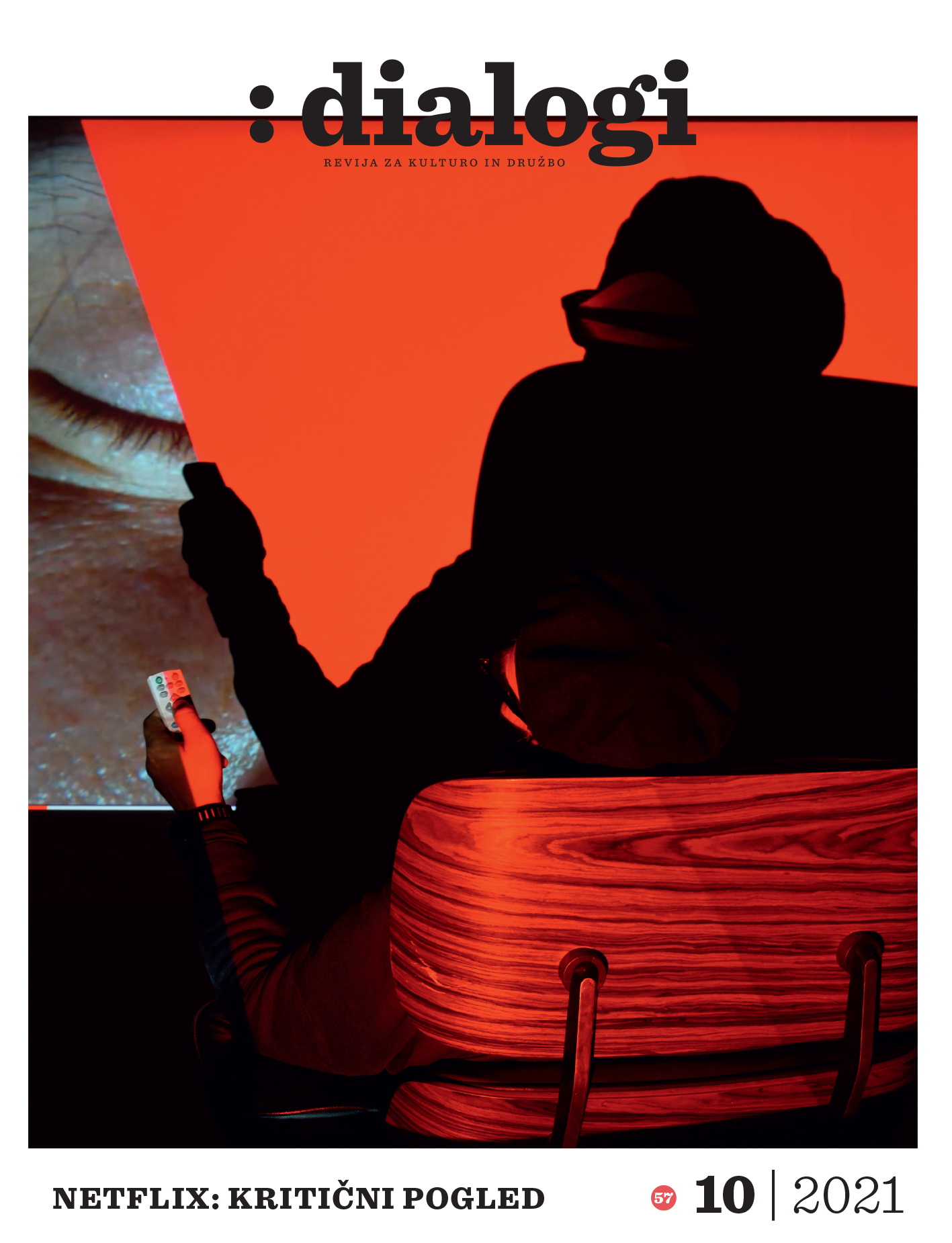

Is Netflix evil?

We have let Netflix into our homes, while rarely questioning whether what it offers us is as limitless as it seems. In a dossier, Tina Poglajen, Žiga Brdnik, Mirt Komel, Jasmina Šepetavc and Matic Majcen question the streaming giant’s technology, programming, strategy and aesthetics.

Netflix is doing any number of things that we are not aware of – but should be. The service does not treat us as individuals but as consumers to be classified into types and classes. It creates the illusion of personalization but, in reality, pursues its own, corporate goals.

‘Unlike Facebook and Google,’ Matic Majcen writes, ‘it seems that we have not yet come round to the view that Netflix is a technology that brings both positive and negative elements into our homes. The purpose of this issue is to shift our perception of this service to the next phase’ … ‘so that each can decide for themselves whether it is a trustworthy brand or whether it is better to maintain a distance from it.’

This article is part of the 1/2022 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.