Matilda Amundsen Bergström revisits temperance – the sixth century ethical cornerstone, dismissed as naïve, if not downright silly in postmodern times – as a means to redefine limits in a seemingly boundless world.

Adaption from graphics by OpenClipArt via Freesvg.org

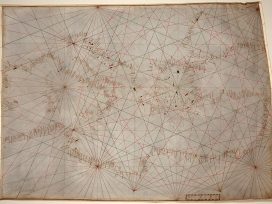

Pope Gregory I, bishop of Rome from 590 to 604 A.D., was convinced that the end of the world had arrived. He lived during the unusually cold and wet period known today as the Late Antique Little Ice Age, which was brought about by volcanic eruptions and variations in the solar cycle. Gregory had no knowledge of the far-reaching effects of ash in the atmosphere or fluctuations in the sun’s activity. But he did know that his whole world was unravelling. The previously so hospitable Mediterranean region had been transformed. Average air temperatures dropped by one degree Celsius. Floods and draughts caused crops to fail year after year. Even with all their technological innovations, the people of Rome were defenceless in the face of such ecological upheavals. Starvation and epidemics ensued, reducing Rome’s population from a million to twenty thousand in the 7th century. Economies collapsed. Political systems broke down. Large flows of migrants changed the European demography forever.

Today, historians argue that the Late Antique Little Ice Age contributed to the fall of the Roman Empire. Gregory, on the other hand, feared that not only Rome’s but all of humanity’s days were numbered – and he thought he knew why. He considered this earthly rebellion against man a divine punishment for an unsustainable, limitless, lifestyle. In their greed, men had traversed ethical, ecological and economical boundaries that should never have been transgressed. According to Gregory, only one thing could pacify God and the angry earth: temperance, the foremost of virtues.

Fridays for Future School strike in Cologne

Photo via Pikrepo

Though the divine explanation has largely been abandoned, in some respects, Gregory’s eschatology uncannily forebodes today’s climate anxiety. Our 21st century is becoming an inverted copy of his lifetime – the Late Antique air temperature dropped roughly as much as present day temperatures have risen, and even though our warmer world has not proved as catastrophic for mankind as Gregory’s colder environment, we are swiftly heading in that direction. The Late Antique climate changes were not caused by human activity – even though the organization of Roman society exacerbated the crisis – but Gregory was convinced that man was to blame for the earthly breakdown, as we know to be the case today. Like a prophet, he proclaimed that greed, voracity and a constant desire for more will make man destroy their only home. 1,500 years later, his predictions are about to come true.

However, Gregory – who was a powerful and influential man – differs from his present-day counterparts on one crucial point. In postmodern society, the idea of temperance – the solution that seemed so obvious to Gregory – feels naïve, if not downright silly. To be sure, climate-related abstinence seems to be somewhat of a trend – restrain from eating meat, from flying – but such self-denial represents something different. It is an aside, a puzzle piece in the construction of identity, an unrealizable, and unrealistic, ideal celebrated by mortified individuals in a hyper capitalistic consumer society where only two options remain: constant growth or breakdown. As a word, ‘temperance’ still exists – though now mostly as a synonym to the more widely used ‘moderation’. But as a concept, temperance is dead, like a metaphor that dies when it is so well integrated into a language that it loses it alienating function and illuminating potential.

Mexico-US border wall at Tijuana, Mexico.

Photo by Tomascastelazo from Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, the questions that the concept originally addressed – questions of boundaries and how to draw them –become ever more challenging. From a certain perspective, our postmodern world is increasingly boundless. Capital and information flow freely between economies, economies that keep expanding while the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere just grows and grows. Moral boundaries, which used to knife their way through love, identities and life itself, are slowly being eroded. From another perspective, borders are continuously drawn around us, closer and closer. Barbed wire fences and brick walls keep people in their place. In autumn 2015 and again in spring 2020, European national borders were consolidated and patrolled to protect the economy and health of ‘our own’. But also voluntarily imposed limits and limitations, acts of solidarity were carried out to protect other people and worlds – not least during this spring, the spring of the pandemic. I want to suggest that temperance, old and unfashionable as it is, could potentially provide us with a tool of the borderline. Not a tool with which we can create new borders or tear down old ones, but one that can help us explore the mechanisms and workings of the self-elected and enjoined boundary.

The concept of temperance – temperantia in Latin and sophrosyne in Greek – was esteemed as one of the four cardinal virtues (the others being prudence, courage and justice) for roughly 2,000 years. These virtues formed the basis of virtue ethics, arguably the most essential ethical system of the Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern world. Virtue ethics entailed many things but designated first and foremost a code of conduct aimed at making people live well together. Virtue ethics weaved together patterns of action, thought and behaviour, which each person (ideally) were to perform for the good of her fellow man, and – since virtue ethics was always the tool of the powerful – for the good of religion and the nation. These behavioural patterns were complex, kaleidoscopic and connected to each person’s class, social status, gender and age. In practice, virtue ethics provided a rule book which helped (or forced) everyone to fulfil social expectations, fit in and keep to their place, in a world where social mobility was unthinkable. But virtue ethics also provided a guide to a good life, in all aspects of the word, implanting above all else the ideal that each individual existence was intertwined with multiple other beings.

Temperance was a centre point in this ethical system – according to Aristotle moderation was not only a virtue in itself but also the founding principle for all virtues. The concept reappears in ethical discussions from Antiquity to the Early Modern period, with a red thread joining Plato’s Charmides, where neither Charmides nor Socrates can quite put their finger on sophrosyne, via Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, where sophrosyne plays an important part, with Cicero’s conduct books for virtuous Romans that popularize the Latin translation temperantia, Thomas of Aquino’s Medieval theology that transforms Ancient ethics to Christian doctrine, and, eventually, Early Modern Republican authors such as David Hume and Mary Astell, who consider temperance a guiding principle for the distribution of political power.

At its core, temperance means finding, respecting and defending boundaries – especially one’s own. This is sometimes equated with a form of non-action, or as abstention from excess and extremes – especially in relation to bodily pleasures connected to alcohol, food and sex. As a concept, however, temperance offers a much richer array of meanings. Philosopher Alasdair Macintyre, for example, has defined temperance as the choice to not use power which is at one’s disposal. Another possibility is to understand temperance as a practice of dispensation – one which includes being without that which one desires, admitting that every fulfilled desire has consequences, and inquiring into desires and their origins. The latter is an especially significant aspect of the Greek sophrosyne, which could be translated both as temperance and self-knowledge. Yet another alternative is to view temperance as a practice of actively being with others, a form of self-restraint which turns one’s attention away from oneself towards others. From that perspective, many currently popular expressions of self-restraint, such as exercise, dieting or voluntary celibacy, are not temperate since they are motivated by the individual’s own desires. Neither do enforced limitations such as laws banning smoking or drugs have anything to do with temperance, since the virtue involves the choice to act in a certain way as much as the action itself – acknowledging the boundary as well as adhering to it.

In his book After Virtue, Macintyre argues that temperance, and virtue ethics, die with their last great proponent, Jane Austen – a poetic way of looking at it. With or without Jane Austen, it is clear that virtue ethics, which insist that every person should curb their desires and give primacy to other people, are fundamentally incompatible with the new world that emerges in Europe and the US during the industrial revolution. Capitalist, individualist consumer society needs the individual and her desires as a driving force and justification for its existence. Therefore, it is wholly unsurprising that temperance was consigned to one of the 19th century ethical backwaters: the sobriety movement, dubbed ‘the temperance movement’ in the 1820s. In a world of more and more extreme capitalism, temperance is gradually emptied of meaning, eventually becoming a hollow decree about abstention in the name of personal health and well-being.

*

Like Gregory, I believe myself to be witnessing the end days. I believe that our thinking and actions, as well as the social and political systems forming aggregates of those thoughts and actions, are about to bring about a collapse. Nobody will need to dismantle the Master’s house. It will fall on its own accord, broken to pieces by the trembles of the very ground on which it stands – if not by an ecological breakdown, from the disintegration of economies or the ravages of pandemic. Before long, somehow, something new must be rebuilt. Could temperance, as an ethical concept, be part of that process? The values that it brings to mind – fitting in, avoiding excess, self-restraint and self-limitation – do not instinctively feel inspiring. Maybe there is good reason why temperance has not benefitted from the recent surge in interest in virtue ethics, no matter how important a concept it once was. So why revive it?

Because we desperately need new and other ways to think about boundary points, limits, borderlines. These are times –this year especially – when boundaries are drawn, transgressed, and drawn again, sometimes within hours and minutes. These are times that urgently require an ethic of the borderline, a different kind of conversation about outer points, about limitations and about how all sorts of boundary lines are incessantly drawn and crossed – in the name of this ideal, that practical reality. Perhaps temperance, a concept where self-limitation and self-knowledge merge, can be part of such a conversation. Perhaps this Ancient concept which is in the midst of a philosophical tradition but outside of today’s political systems – no longer the Master’s tool – can call to mind other worlds and views. And perhaps temperance, once the centre point of virtue ethics, can provide a steppingstone towards a new ethical order – one that our both warmer and colder world requires.

Published 19 August 2020

Original in Swedish

First published by Glänta 1-2/2020 (Swedish version) / Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Glänta © Matilda Amundsen Bergström / Glänta / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Prisoners of conscience

A conversation with Myroslav Marynovych

Defenders of human rights often face high stakes. When the Ukrainian Helsinki Group openly challenged the Soviet Union in the name of the 1975 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, young dissidents soon became political prisoners. The price for being a non-conformist was steep yet encouraged solidarity, paving the way to Euromaidan.

Unmasking naked delusion

Tangent

Ever been had? Led to believe a lie, an untruth? Realized the con too late? It can happen to anyone. Deception is rife. But so too is delusion. ‘Tangents’, a new Eurozine editorial feature, takes a critical look at the duplicitous pair.