Faire l’idiot!

Being an idiot might be exactly the subversive tool we need in our communication-obsessed world, suggests Miriam Rasch. In times of heightened surveillance capitalism, non-communication can become active interference. It might not quite be time to throw away your phone, but inefficiency and deceleration could be useful tools.

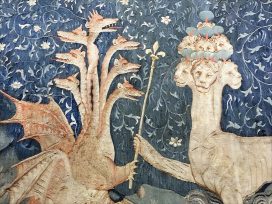

Adaption from graphics by OpenClipArt via Freesvg.org

‘The idiot does not “communicate”’,2 writes philosopher Byung-Chul Han in Psychopolitics. He may speak, sure, but not to convey a certain message. That makes the idiot instantly subversive in our time, where communication counts among the highest goods. Not so much because we value the exchange of information or because we can learn from each other. But rather, because the ever-accelerating, 24/7 communication cycle is what keeps surveillance capitalism going. It feeds the database and helps train algorithms. If everyone were to quit Facebook and Instagram right now, would stop emailing and messaging and throw their smartphones in the ditch – in other words, if all communicative data flows would rigorously come to a halt – then capital would stop flowing too. Capital that is entangled with the interests of those who want to keep an eye on us, whether it’s governments, security services, or companies like Cambridge Analytica, who sell the dream of propaganda with guaranteed return on investments to whatever political ideology that is willing to pay for it. The means: data profiles. The source: ‘total communication’. The goal: ‘total surveillance’, as Han calls it.

However, in order to generate useful data someone has to move, just like you have to speak in order to be tapped. Therefore, silence and a standstill signal the end of the society of control. The idiot knows as much.

“Faire l’idiot”! Be an idiot! In his 1987 lecture Qu’est-ce que l’acte de création? (What is the Creative Act?), Gilles Deleuze used these words to point out the idiot as a positive example for philosophers and all others who want to think in order to act upon the world. The idiot creates a private space for thinking, in which new things can happen. He is ‘a conceptual persona’, explain Deleuze and Guattari in What is Philosophy?3 Since then, the pressure to communicate and be transparent has only increased. And with them, so has the need for ‘free spaces of silence, quietude, and loneliness’, as Han calls them, in which private thinking might take place. Should we throw out our smartphones, then, and take a vow of silence? No, that too would become predictable in the long run. And, if anything, the idiot is unpredictable and shouts ‘Pinkpop’ in a Lowlands tent.

Photo by Florian Klauer from Unsplash.

The archetypical idiot that Deleuze returns to in What is the Creative Act? is Dostoevsky’s. There’s something strange going on with Dostoevsky’s characters, he says. They suffer from chronic unrest and allow themselves to be constantly distracted by minute things. ‘A character goes out on the street and says: “Tanja, the woman I love, asks for my help. I’ll go, quick, quick, she will die if I don’t go!” He walks down the stairs and meets a friend, or he sees a dog that has been run over and he just forgets everything. He completely forgets that this Tanja is waiting for him, all the while dying. He starts talking, meets another acquaintance, has a cup of tea with him and then suddenly, again: “Tanja is waiting for me, I have to go!”’ These characters are constantly engaged with all kinds of emergencies and yet there is always something more important happening. But what is that something? They can’t get a grip on it and neither can we.

Well, how is that an exemplar? Forgetting people in need, being in a constant state of readiness… I’d rather pass. What makes the idiot an imitable figure for our time, however, is his fundamental ‘inefficiency’. His refusal to rationalize choices and actions. His reliance on intuition while knowing it cannot be dissected. His innocence. Make no mistake: the idiot is not a con artist. The liar knows the truth and wants to hide it; that is his goal. The liar still communicates, wants to sell you something. He provokes, nudges, tries to persuade and uses all techniques available, befitting the paradigm of total communication and total surveillance. The idiot doesn’t care about the truth. In the end, he has no message to proclaim.

What the idiot teaches us, according to Isabelle Stengers, is rather the value of delay and the ‘suspension’ of truth.4 Although Dostoevsky’s Ur-idiot seems an early adopter of ADHD, Stengers points out that the idiot’s non-communication more than anything causes deceleration. One thing does not lead to the next. There’s no moving forward. He wants nothing to do with causal relations; ‘and so…’ does not belong to his vocabulary. Something could always happen that has nothing to do with what came before: a chance encounter, a dog run over, a cup of tea.

And so, the idiot lets the machine of total communication and total surveillance come to a crashing halt. He leaves you speechless and makes you laugh at the same time, as happened to me at that festival stage. To stutter and to laugh are both literally delays in communication, results of an unexpected turn and the opening of another unpredictable turn. Idiotism, says Han, is therefore a practice of freedom – perhaps one of the few that we have left. At heart, this freedom consists in ignoring the need for intelligibility. It is poetic freedom, you might say, almost a hippie-like freedom. In the words of Botho Strauss, with whom Han also concludes: the idiot is a being ‘more like a flower: an existence simply open to light’.5

Disclaimer: This text duplicates in places passages contained in other articles published by the same author.

Pinkpop is the name of a large music festival in the Netherlands, next to the Lowlands festival.

B-C. Han, Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power, Verso, 2017, p.84.

G. Deleuze and F. Guattari, What is Philosophy?, H. Tomlinson and G. Burchill (trans.), Verso, 1994.

I. Stengers, ‘The cosmopolitical proposal’, L. Carey-Libbrecht (trans.), in B. Latour and P. Weibel (eds.), Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, MIT Press, 2005.

B-C. Han, Psychopolitics, p.87.

Published 19 August 2020

Original in Swedish

First published by Glänta 1-2/2020 (Swedish version) / Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Glänta © Miriam Rasch / Glänta / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

It has become axiomatic in our distrustful age that truth stands in tension with friendship. But the traps of identitarianism require that we rehabilitate our relation to truth – and understand it not as the opposite of friendship, but its very condition.

Perceiving war as a series of strategic manoeuvres delineated on a map renders a horizontal view of conflict. And projecting an end to fighting is fundamentally restorative. But deep pollution, as is occurring in Ukraine from Russia’s radioactive colonialism, warns of a more persistent dimension with long-term environmental impact.