The hippies of Soviet Lviv

Hippies are well known as a phenomenon of the West. But this counterculture, which inspired an entire generation, took root in an unlikely place – the Soviet Union of the 1970s.

If, in the United States, the hippie movement was born as a protest against capitalist values, and later also as a protest against the Vietnam War and war in general, in the Soviet Union ‘capitalist values’ were categorically impossible. Those who spoke out in opposition to, for example, the suppression of the Prague Spring in 1968, were a handful of Soviet dissidents, not local disciples of the American hippies. In fact, the hippie movement in the USSR was quite small in comparison to the analogous movement in the United States, where hippie festivals brought together as many as half a million participants.

American hippies, protesting against the capitalist system, created a new market, even if they themselves did not recognize this at first: products for hippies. Clothes, music, accessories. The flexible capitalist system quickly and adeptly reacted to the appearance of a new group of consumers. As a result, or perhaps this was the case from the beginning, the main marker of hippies became their outward appearance, fashion and the music they listened to, not their ideology or social and political activity. If the market reacted to the existence of hippies, American society remained more or less indifferent to this phenomenon.

Soviet hippies, in contrast, incurred not only undue attention from the KGB and police, but also a negative reaction from ‘socialist society.’ There could be no freedom of expression in the USSR, and that meant that an outward appearance that was provocative from the point of view of Soviet morality was sufficient for a person to be counted among the enemies of the Soviet system. Soviet hippies could not escape pressure or close scrutiny from the society that they placed themselves in opposition to. This pressure, along with their common interests and common fashion, also fostered a desire to unite, to interact more with like-minded people, to seek out and sustain close ties with hippies from other regions.

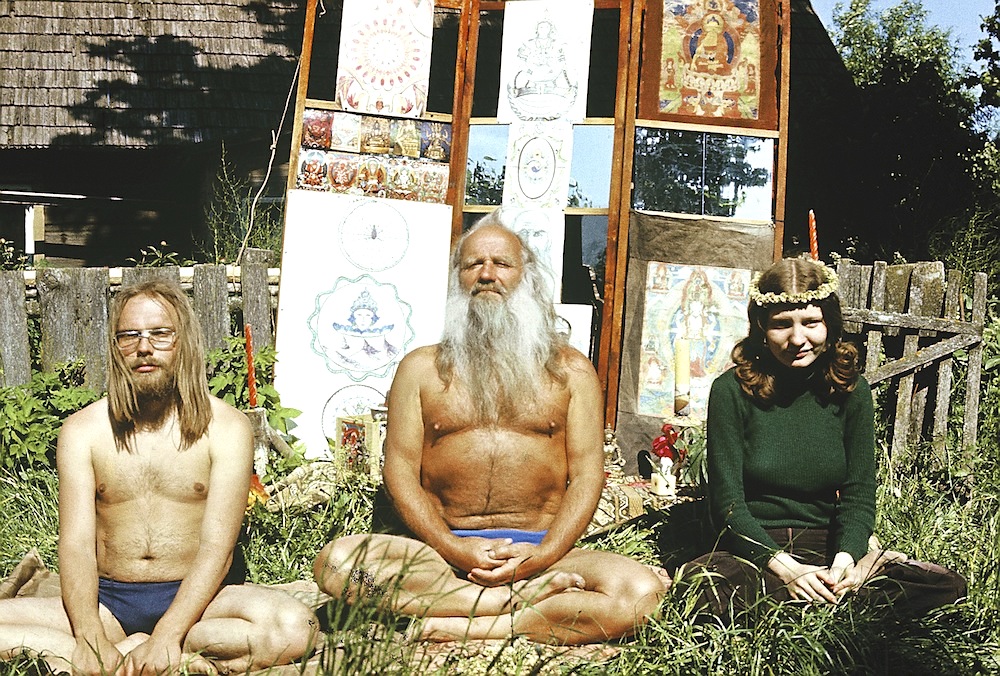

Mihkel Ram Tamm (centre), Estonian philosopher and expert on Sanskrit, yoga and meditation, became a guru for many hippies in Soviet Estonia and elsewhere in the USSR. This photo appears in the documentary film Soviet Hippies, directed by Terje Toomistu. Photo: Courtesy of Vladimir Wiedemann.

From time to time, Soviet hippies tried to create their own organizations. What was the main factor behind this: mockery, parody, or a subconscious expression of the Soviet ‘collective’ experience? It is likely that every group of hippies that decided to ‘get organized’ had its own reasons and justifications. Perhaps a role was also played by school history lessons, during which teachers explained that all important events were linked to ‘collective action by like-minded people’: from the 1825 Decembrist Uprising to the Young Guard, an underground Komsomol organization active during the Nazi occupation of Ukraine.

Anarchism and passive protest

There were various ways of organizing. In major Soviet cities at that time, instead of forming an ‘organization’ hippies simply chose a meeting place. In Kyiv, the hippies and local ‘bright young things’ gathered at the café Khreshchatyi Iar on Prorizna Street. In Leningrad, the spot was a café commonly referred to as Saigon. In Lviv, the hippie meeting place was Virmenka, on Virmens’ka Street. But the ‘collective’ history of Lviv’s hippies begins with the informal association Republic of the Holy Garden (Respublika Sviatoho Sadu).

‘We founded the Republic of the Holy Garden on 12 October 1968,’ wrote Il’ko Lemko, one of the first Lviv hippies, in his memoirs. ‘It was 14-18 boys with a thirst for freedom, even some sort of anarchism and passive protest against the Soviet madhouse, playing at politics. Kazik [Dmytro Kuzovkin, one of the initial members] drew a crest in white paint on a green flag, and the crest represented a Ukrainian trident (tryzub)(…). Under the trident there were two crossed walnut tree leaves – the sacred plant of the Holy Garden – and between them a soccer ball.’

During Soviet times, the trident, today pictured on Ukraine’s crest, was a forbidden symbol, linked to ‘bourgeois Ukrainian nationalism.’ The KGB fought tirelessly against Ukrainian nationalism, and in Lviv, the cradle of the Ukrainian national movement, this was of course something everyone knew about. For the most part, Ukrainian hippies were not nationalists. What’s more, the common language among hippies from various regions of the USSR was Russian. Lviv hippies regularly welcomed their counterparts from the Baltic countries, Moscow, and Leningrad. So depicting the trident on their ‘crest’ was more of a jokey challenge to the Soviet system, which Soviet hippies set themselves in opposition to.

The Republic of the Holy Garden was a space of freedom, the size of two soccer fields, protected by the walls of an old Carmelite monastery. It was an ideal place for those who wanted to hide from Soviet reality. At its peak, it brought together 60-100 Lviv hippies, and the concerts they organized there sometimes drew as many as 300 fans of banned rock music. United not simply by a regular meeting place, but by their ‘own’ territory, it did not occur to the majority of the Republic’s hippies to organize further, to come up with rules, ‘rights and responsibilities.’ New hippies were simply ‘inscribed’—that is, their presence was verbally approved, and this was enough for them to become part of the group. But for some Lviv hippies, the Republic of the Holy Garden and its unofficial rules were not enough. They tried to create their own organizations with stated goals and rules, in which there was sometimes an element of mocking Soviet reality, and the Komsomol in particular. But sometimes ‘Soviet collectivism’ showed through in their actions.

Illegal hippie organizations

In the Lviv regional archive you can read reports from the regional Komsomol organization about two attempts to create illegal hippie organizations in Lviv. One was in the first half of 1970. Seven long-haired students began their organizational activity with secret meetings in the basement of a residential building. There, amidst sewerage lines and other utility pipes, they built campfires and discussed the future structure of the organization and how high to set the dues each member would have to pay to finance the organization’s activity. The parents of one of the participants in these meetings suspected that their son had fallen in with a bad crowd and went to the police to ask them to ‘save their child.’ As a result, this group of hippies trying to found their own secret organization was arrested on 23 June 1970. ‘Preventative meetings’ were held with them; several were expelled from university and from the Komsomol.

In October 1970 a second, larger group of young Lviv hippies, totalling 21 people, also decided to create their own organization. The leader of this group was Viacheslav Yeres’ko, nicknamed Sharnir – a colourful individual, a young and charismatic long-haired invalid, who got around on crutches and wore a long leather trench coat. They didn’t bother hiding in basements, instead gathering outside, often on the steps of the Dominican cathedral. Their founding meeting was held on 18 October. At this meeting, the members of the group voted on the text of their Manifesto as proposed by Yeres’ko, and on the organization’s anthem. They approved dues ranging from 50 kopeks to 3 roubles per month. This money would be used for group activities, including going to the movies and visiting cafés. They also elected a president – of course, the initiator himself, Viacheslav Yeres’ko.

The group’s next meeting was set for 7 November – the anniversary of the October Revolution – at Yeres’ko’s house in Briukhovichi, a suburb of Lviv. The young hippies who came to this meeting were greeted at the door by their ‘president,’ dressed in a black shirt with Nazi symbols. Several members of the group immediately left. Others remained and listened to a fiery speech given by Sharnir. Its contents are recapped in a memorandum now held by the Lviv regional archive: Viacheslav Yeres’ko espouses ‘anti-Soviet views, fostering hatred towards the volunteer public order militia (druzhinniki) and the Komsomol, asserting that the Komsomol is made up of drunkards, imposters, hooligans.’

Viacheslav Yeres’ko loved to recount to his young confederates how, during the Prague Spring, Czech hippies ‘helped shoot communists.’ Another favourite subject of his was the history of the struggle of Ukrainian nationalists from the Ukrainian Insurgent Army against the Soviet Union. He was a clear opponent of traditional hippie pacifist views.

The history of this organization came to an end on 26 November 1970, when the police came and searched the house of its ‘president.’ This search revealed a slew of fascist paraphernalia, plus a Walther pistol. Viacheslav Yeres’ko was sentenced to three years in prison. All the group’s members were rounded up; some were expelled from university and sent to the army, and all Komsomol members were expelled from that organization.

Provocation from the KGB?

The local press wrote a great deal about hippies professing the ideology of bourgeois Ukrainian nationalism and about their attraction to fascist ideas. To combat them, druzhinniki of ‘Komsomol task units’ were ‘deployed,’ under the command of KGB officers. These druzhinniki – young guys between the ages of 14 and 27 – ‘caught’ long-haired men on the streets of Lviv and dragged them to police stations, where they were photographed, their details were taken, and they were fingerprinted. Sometimes the druzhinniki took scissors and cut off their long hair.

At the same moment, in various cities across the Soviet Union, the KGB arranged various provocations directed against hippies, as a result of which some of them ended up in prison on charges usually not related to political activity. They were convicted of hooliganism, drug use, and vagrancy. The story of Viacheslav Yeres’ko and his organization could plausibly have been a KGB provocation.

In any case, it was the only court case in which a representative of the hippie movement was accused, at least at the beginning, of bourgeois Ukrainian nationalism. He was not sent to prison on political charges, however, but on criminal ones: for possession of a firearm. And he was sentenced only to three years, which was unbelievably little for that time. This indirectly supports the view that the entire story of the attempt to create an organization of hippie militants was a KGB provocation.

By the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union the hippie fad among young people had already passed, but the first hippies, who had become devotees of the movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s, stuck to their ideals and principles; by then, they were seen as political dissidents, activists opposing the Soviet authorities.

This is probably why it now seems logical that when the first representative body of Amnesty International in Ukraine was founded in Lviv in 1993, it was with the participation of both the former dissident and political prisoner Myroslav Marynovych and a group of ‘first generation’ hippies led by Alik Olisevych, one of the founders of the hippie movement in Ukraine.

Andrey Kurkov was a Sheptyts’kyi Visiting Fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) from January to March 2017.

Published 30 June 2017

Original in Russian

Translated by

Kate Younger

First published by IWM post No 119 (Spring/Summer 2017)

Contributed by IWM Post © Andrey Kurkov / IWM / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Russia’s orbit

Osteuropa 4/2024

Repression, murder, war: on the logic driving the Putin regime toward ever-greater excesses of violence. Featuring Yuri Andrukhovych on the Russian colonial empire – the only ever to have tried to reconquer a former possession. Also: articles on Navalny, and on what next for Georgia?

The difference between knowing from distance that war is being waged and living that reality couldn’t be more extreme. But can awareness of multiple repercussions turn protective disassociation from violence into active solidarity? ‘The Most Documented War’ symposium in Lviv, Ukraine, provides valuable pointers regarding engagement and responsibility.