The ethos of journalistic independence that flourished in the USSR during glasnost degenerated, in the following decades, into political partisanship and commercial opportunism. In today’s Russia, self-censorship and tact are regarded as survival skills in a much-diminished sector.

Thirty years ago, Mikhail Gorbachev, the young and energetic general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, introduced the policies of glasnost – his attempt to grant freedom of speech to the Soviet people. For a society that for sixty years had lived in a state of total state censorship, this was a massive step forward. Within a couple of years, the first independent media outlets had emerged. Journalists began challenging the authorities and rapidly became heroes for millions of Soviet citizens.

Then, amidst this sudden liberalization, came the August putsch of 1991 and the reintroduction of state censorship. Leading media critical of the regime were closed down. Back then, however, they could not be silenced so easily; they found the courage to resist, joined forces and published a newspaper condemning the plotters. At a press conference on 20 August 1991, a young and casually dressed journalist, Tatyana Malkina, asked the putschists a direct and tough question: ‘Do you realize that you have just committed a coup d’état?’1 It would be hard to imagine such impertinence even towards a middle-rank bureaucrat, let alone a Soviet leader, in the decades following the Bolshevik revolution.

The inability of the putschists to respond with force to the first signs of civil disobedience was the last nail to the coffin of the Soviet power. The generation of journalists that emerged during perestroika helped discredit the plotters and brought major changes to intra-elite relations. Four months after, on 25 December 1991, Gorbachev made his final televised speech as the first and last Soviet President announcing the collapse of the Soviet Union.2

What happened next belongs to the history of the post-Soviet Russian media. In the first decade of independence, journalists played a significant role in political and economic events. Gradually, however, they lost their independence and evolved into ‘soldiers’ who served the regime, at times spreading blatant lies. A look at Russian journalism of that time reveals a disheartening lack of solidarity. Violence against journalists very rarely inspired protest. Anna Politkovskaya’s murder in 2006 was a notorious example of how the journalistic community responded to the threat to itself and to one of its members. It did literally nothing.

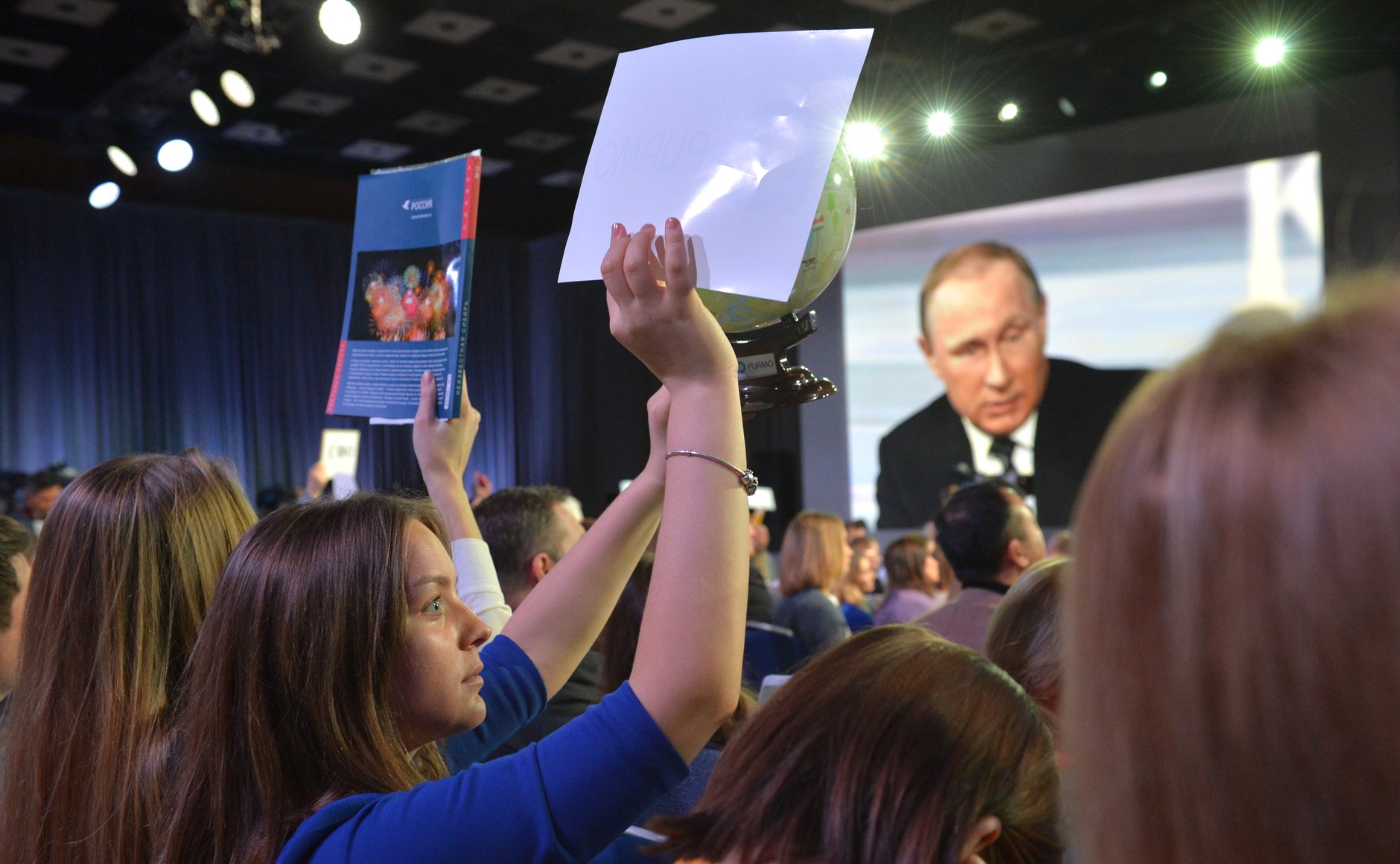

Press conference with Vladimir Putin. Source: www.kremlin.ru / Wikimedia

The short life of Russian media freedom

What happened to the Russian journalists of perestroika? How and why did they evolve from beacons of freedom brave enough to show the other side of the Soviet life to hatemongers who spread falsehoods such as the story about the crucified boy in Eastern Ukraine?3

Today, perestroika is often considered to be the freest period in recent Russian media history.4 Gorbachev and his liberal aides, first and foremost Aleksandr Yakovlev, the head of the propaganda department in the Central Committee, had eased censorship and got rid of the Brezhnevite old guard that had controlled state television and radio. Yakovlev personally backed liberal editors-in-chief and promoted stories that aimed to further support for moderate, regime-critical voices. As the Russian journalist and media expert Nataliya Rostova notes, the cracks in the Soviet media system at the end of perestroika allowed dissenting media managers to challenge the Soviet leadership while retaining their high-ranking positions.5

At the same time, state control of the media did not evaporate. Rather, the Kremlin’s hand became too weak to control rebellious media outlets. Even if a published or broadcast story was not favorable to Gorbachev and his circle, it was hard to stop it from spreading in a society hungry for news and revelations about the past and present. Censorship became easy to avoid.

Natalya Gevorkyan, a prominent journalist who during the 1980s worked at Moskovskie Novosti – the vanguard media outlet of perestroika – recalls how, when state censors embargoed an issue carrying one of her stories at the last minute, print workers turned the presses back on once the censors had left the building.6 Such a thing was absolutely unprecedented in the Soviet Union.

Although journalists criticized the state during perestroika, the state nevertheless paid their salaries, thus inadvertently supporting the gradual rocking of the Soviet boat. In this short period of almost untrammeled freedom, journalists and media managers had no reason to worry about finances and could focus on their journalism.

Another important feature of the journalistic profession during perestroika was journalists’ new proximity to politicians. Glasnost opened the gates to an emerging political elite that opposed the communists. The new generations of journalists and politicians were united against the common opponent – the Soviet regime. This meant, on the one hand, that they were both hostile to the structures of power and yet close to it. This not only reinforced the popularity of politicians, but cast a spell on the journalists. In the 1990s, they continued to support politicians, especially those who stood with them against Soviet power, even when the goals and values of these politicians changed dramatically.

Yeltsin’s Russia: The crusade to save ‘democracy’

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the turbulent change in economic circumstances in 1992 fundamentally reshaped the Russian media. On 2 January 1992, Yeltsin’s government launched radical liberal reforms aimed at taking the country out of economic backwardness. However not all media outlets were ready to praise the free market: galloping inflation, paper shortages and delays in salary payments prompted media managers to ask the Kremlin for help. The first Russian president agreed to support the media. Alongside financial maintenance, the Kremlin turned over the property of media outlets to their managers.7 As a result, many of the media managers became rich, and their taste for the good life became even stronger when the oligarchs started funneling their money into the press. At the same time, rank-and-file journalists had to search for other ways to survive financially. As a result, concealed advertising became a part of everyday journalistic practice and dzhinsa – a term for paid news – became rampant and widely acceptable.

In the first years of Yeltsin’s rule, the community of elite journalists, some of whom formerly worked for foreign media, organized a closed club where they regularly met with prominent politicians: the Moscow mayor, MPs, government ministers. Called the Moscow Charter of Journalists, it was the first attempt after the collapse of the USSR to formulate the principles of journalism. Nevertheless, the attempt failed because the conclusions reached were not disseminated among other colleagues. Professional though the Charter members may have been, journalist community-building was not top of their agenda.

The biggest shock to the profession came during Yeltsin’s second presidential term. In 1996 Yeltsin entered a tough run for the Kremlin’s office that required him to defeat Gennady Zyuganov, the contender from the Communist Party. Given the dire financial and political situation in the country, Zyuganov stood a very good chance of winning. For most people in the media, this prospect was a nightmare: their career achievements were at stake. With the support of the wealthiest men in the country and Kremlin staff, a group of media professionals embarked upon a large-scale media crusade against the Communists, and a character assassination of Zyuganov, in particular. Yeltsin won, but the cost paid for this war of words was dramatic.

Interviews with media professionals today reveal how polarized the Russian media community remains when it comes to the assessment of the 1996 elections. Some, especially the generation of the 1990s, believe that what they did was right. They were protecting democracy from the return of communism. Journalists of the younger generation, in contrast, blame their predecessors for compromising the integrity of the profession and paving the way to the problems Russian media face today.8

At any rate, the campaign to sling mud at Zyuganov revealed the power of the media to indoctrinate the Russian population. It also showed how lucrative it could be both for the Kremlin and for the oligarchs to control and exploit the media for political and financial goals. The end of the 1990s was the era of the ‘information wars’ waged between the oligarchs over influence and wealth. The result was that both elite and rank-and-file journalists evolved into full-time courtiers of their owners. Their task was to produce content that would satisfy their owners and damage opponents as much as possible. As long as top journalists were receiving perks from financial tycoons, there was no room for professional principles. Mutual attack became a daily routine for many journalists and eventually led to hostility amongst colleagues and suspicion about their sincerity. The ‘information war’ was the final blow to solidarity within the Russian journalistic profession.

The media in Putin’s Russia: The hand that feeds

Further attempts by the Kremlin in the 2000s to bring the media under closer control exploited these internal divisions. It is commonplace in academic literature to start the history of Russian media in the Putin era with the case of NTV – the television channel owned by the media tycoon Vladimir Gusinsky. Gusinsky fell out with the Kremlin on the eve of Putin’s first elections in March 2000. In 2001, the state-owned company Gazprom seized his assets. The channel’s core team of journalists and media managers moved to another channel in protest. However, they failed to gain support from their colleagues, who remained silent: after the ‘information wars’, very little trust remained among media professionals. Almost nobody in the community raised their concerns about how morally weak and vulnerable journalism had become.

It is fair to say that, by the time Putin came to power, journalists had already lost the credibility and independence they had gained under Gorbachev less than fifteen years before. As one journalist noted in an interview with me, the ‘information wars’ caused Russian journalists to become ‘spineless’ and ready to obey their boss’s every word. The Kremlin did it its best to reduce the market for non-state affiliated media. In 2017, there are very few dissenting voices left in the country; the rest of the media know their place. When work is in short supply, one inevitably comes to heel. Obedience towards owners and the gradual restructuring of the media landscape by the state has made self-censorship one the most valuable of journalistic talents.

Russian journalists have a peculiar perception of self-censorship, often praising it as a professional skill rather than an obstacle. In interviews with media professionals at both elite and rank-and-file levels, the concept of adekvatnost – literally a sense of appropriateness derived from knowledge of the political situation and an intuitive awareness of boundaries – is a recurring theme.9 Skill in adekvatnost is said to be essential for success, since it allows one to anticipate how the line to toe will be drawn in the future. The peculiarity of the Russian situation is that, whilst self-censorship makes the media content dull and boring, adekvatnost ensures the right balance between entertainment, originality and political limits. In a country where the stability of the regime heavily depends on what is shown on screen, being boring is the last mistake the authorities want to make.

The striving to keep the audiences interested, loyalty to the media owner (be it the state or an oligarch), and the need to constantly navigate the murky waters of Russian politics, leaves no room for professional principles. One journalist who has been working in the branch for twenty-five years, put it this way: ‘Don’t let the facts spoil a good story’. This watchword perfectly encapsulates the nature of Russian journalism today: the absence of a self-regulating professional community and the constant pressure of the state turns honest journalists into a rare breed.

What are the prospects for Russian journalism? Does it make sense to expect the situation to improve in the immediate future? While the present is grim and unsettling for freedom of speech and independent journalism, passionate discussion among Russian media professionals about the working principles occurs regularly on and offline. A new generation of journalists, born in the late-1990s and the 2000s, can potentially bring change if it takes on board the lessons of the last thirty years. Russian journalism might be going through very troubled times, but it still has a chance to restore its integrity.

'Malkina protiv GKChP', Youtube video, posted 6 March 2011, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5AIXc6zMuRY, accessed on 17 February 2017.

‘Gorbachev resigns: December 25, 1991’, Youtube video, posted 23 September 2011, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lPjMh1zpEo, accessed on 17 February 2017.

‘Kremlin ”crucifixion” tale: Russia’s First Channel comments on notorious “crucified boy” report’, posted 22 December 2014, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V-j6wha1gx0 ,accessed on 17 February 2017.

Nataliya Rostova, ‘Rozhdenie rossiiskikh media’, available at http://gorbymedia.com/page/about, accessed on 17 February 2017.

Nataliya Rostova, ’13 oktiabria 1989’, Rozhdenie rossiiskikh media, available at http://gorbymedia.com/post/10-13-1989, accessed on 17 February 2017.

Personal communication with Natalya Gevorkyan.

Vasily Gatov, Putin, Maria Ivanovna from Ivanovo and Ukrainians on the Telly (the Henry Jackson Society, 2015), p. 3.

See Elisabeth Schimpfössl and Ilya Yablokov, “Power Lost and Freedom Relinquished: Russian Journalists Assessing the First Post-Soviet Decade” Russian Review, 72, no. 3 (2017).

Elisabeth Schimpfössl and Ilya Yablokov, “Coercion or Conformism? Censorship and self-censorship among Russian media personalities and reporters in the 2010s,” Democratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 20, no. 2, pp. 295-312.

Published 16 June 2017

Original in English

First published by Razpotja 28 (2017) (Slovenian version)

Contributed by Razpotja © Ilya Yablokov / Razpotja / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Internal empire

Osteuropa 1–3/2024

Why the Russian Federation is a de facto empire despite the 1993 constitution; why Putin’s imperial but anti-ideological variety of Russian nationalism dominates; why Chechnya remains an open wound on the body politic; and feeling the impact of the Putin regime’s clampdown on intellectual freedoms.

‘Occupation is like a flood. The water doesn’t reach every house at the same time. First it covers the roads until it meets an obstacle – a wall or a fence. Then it starts to rise, finding cracks, seeping further, conquering one house after another, together with everything inside them.’