I have been researching Russian cyber warfare and intelligence capabilities for more than a decade, and for all that time its significance and soft power was underestimated in Georgia. In order to assess the nature of ongoing Russian cyber operations against Georgia, we should start with the basics to better understand the role of cyber-security in today’s global security environment.

For decades, the world’s most harmful threats were radical groups, terrorists and criminal organizations, intelligence agencies and military regimes. The weapons feared around the globe were weapons of mass destruction: chemical, biological, radioactive and nuclear. But there has been a significant shift in the global security landscape: after decades of a nuclear arms race between Russia and the United States, both shifted from being nuclear powers to cyber powers.

Cyber capabilities are mostly hidden and can be used by anybody, and are thus more dangerous than traditional weapons. New threats are emerging as technology advances and we are now facing a fifth-dimensional warfare: the silent war.

Russian capabilities

Cyber operations are cheap, easily accessible, inconspicuous – sometimes even stealthy – and have the element of plausible deniability. Cyber capabilities currently play a crucial role in collecting intelligence information and even conducting military operations. Threats from cyberspace can also create real, lethal damage in real life.

The first thing to know about Russian cyber capabilities is that most of them are not that cyber at all. State-sponsored cyber-crime involves almost every law enforcement agency and special services, because of a ‘securitization’ scale in the Russian government. It also involves private companies, criminal organisations, NGOs, media, academia, the expert community, activists and individuals who have a key role not only in cyber operations, but in the extensive propaganda campaigns.

Russia, obviously, has a huge intelligence collection system, which was underestimated for many years. It has been growing and sharpening since the days of the KGB, which was once the strongest intelligence agency.

What exactly are Russia’s cyber offensive capabilities? Some examples are the very popular Cozy Bear / APT29 and Fancy Bear / APT28, the youth activists Nashi, one of the world’s biggest anti-virus companies Kaspersky, the private company Russian Business Network (RBN), and many others. Some IT companies implanted in countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) can also be tools for Russian intelligence services, gathering useful real-time data.

One more example is Russian internet service providers (ISPs), which are both defensive and offensive tools. They can stand as an alternative and compelling communication channel with lots of features in case something goes wrong. They serve as an offensive tool since, through its structure, the ISP’s customers can act as individual bots, which can be used to launch powerful cyberattacks such as ‘Layer 7’, with new innovative forms of technical manipulation. During the years of my research, I have found hundreds of organisations, but the above-mentioned ones are the key players and, more importantly, the most relevant existing Russian cyber-offensive operations.

It is also important to understand the philosophy behind Russia’s cyber capabilities since eastern and western players have a different attitude when it comes to cyber operations. Cyber operations conducted from the West are government and military-affiliated, while in the East they are mostly non-state players, such as the Russian business network (an online cyber mafia) or the Syrian electronic army. The point is that non-state actors have no proven link to a governmental entity. The West is, therefore, using cyber capabilities as a governmental asset, while the East maintains plausible deniability.

Simple methods

The first and most important event in Russia’s cyber attacks against Georgia can be traced to the 2008 war, which was the first real official cyberwar in history. This is an issue of special importance for me as I had the opportunity to witness the events up close. This war strongly inspired me to lay the foundation for pioneer cyber-security institutions in the Caucasus region through the Caucasus Academy of Security Experts (CASE).

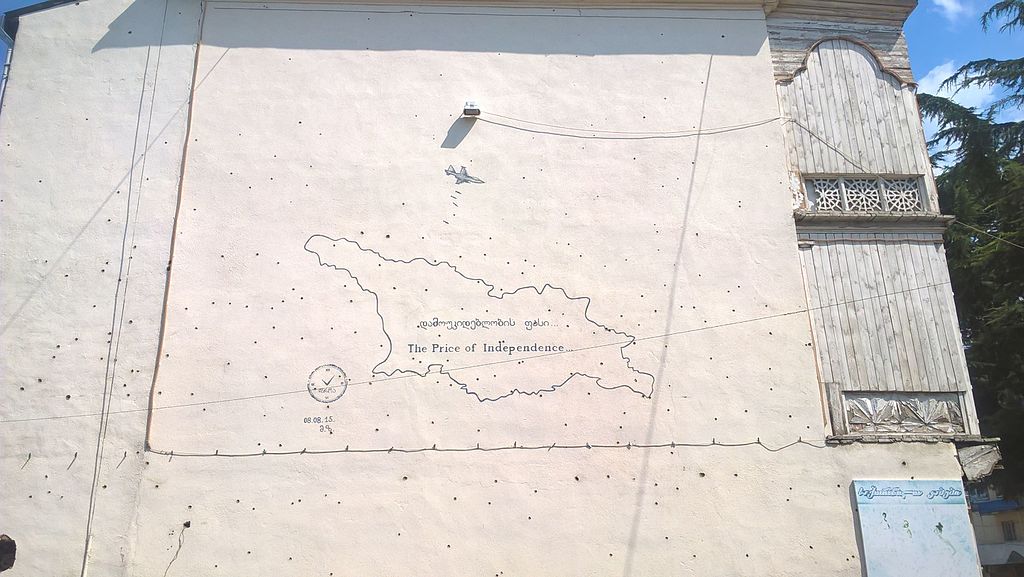

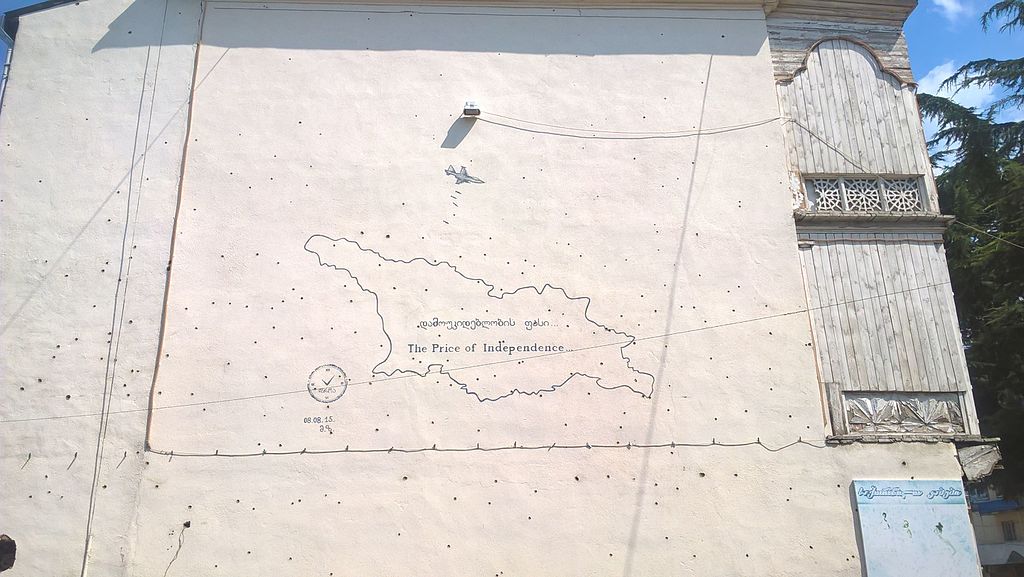

In August 2008, Russia was preparing for a military invasion in Georgia, laying its foundations through propaganda and cyberattacks to position itself as a ‘peacekeeper’. While the whole world was shocked by Russian aggression and the actual military warfare taking place on Georgian soil, the war was also unfolding in cyberspace.

Damaged wall of the residential building in downtown Gori after Russian bombardment with cluster bomb during 2008 war. Photo by Giorgi Balakhadze from Wikimedia Commons.

First were the massive cyberattacks against important targets that were clearly strategically chosen: information agencies, blogs and media outlets. Then came governmental agencies and institutions which were the focal endpoints of the Russian strategy – the Georgian ministry of foreign affairs, consulates, embassies and foreign missions, as well as the official website of the president’s administration. It became clear that the attacks were about disabling our information resources in order to minimise the ability to fight Russian propaganda during its offensive.

Even though Russia successfully executed cyber attacks against well-defined targets, analysing the targets is not enough to see the bigger picture – timing and methodology are equally important. Interestingly enough, and despite the complexity of the campaign, the methods used were not so innovative.

At first, Russia needed tactical planning to conduct the campaign in a way to maintain plausible deniability: the attacks could therefore not originate from government infrastructure. Russia had extensive target lists, only a short period of time, and a need for machine power – they needed to find an alternative to government centres. What the Kremlin had, though, was a large population connected to the internet. Instead of running a network from powerful government servers, they used hundreds of thousands of internet users and their computers by infecting them with the ISP’s and FSB’s help.

This way the Kremlin was able to maintain plausible deniability. The network of zombie computers had even more machine power than the government’s infrastructure, and could also provide them with time, since it was very difficult to track the source of attacks. A special system designed to intercept and manipulate local Russian networks, called SORM, came in handy during such operations.

The botnet was launched and all the above-mentioned targets were attacked successfully. It is important to note that the aim of this campaign was to not steal information, but to disable it. Russian intelligence officers and affiliated groups on social media were sharing special software along with a list of targets to attack Georgian resources. One of the tools that I have retrieved and analysed from the Russian forum is explicitly designed for denial of service (DoS) attacks, which disables websites from functioning.

Lessons

The campaign against Georgia was similar to the attacks against Estonia in 2007, when Russian intelligence services started aggressive cyber operations amid a disagreement related to the relocation of the Soviet monument of the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn. Yet the operations monitored in Estonia in 2007, in Lithuania (2008), and in Iran (2009) were never officially declared cyberwars.

In order to define cyber attacks and cyber war as such, countries must either have legislation defining the specific character of such operations, or cyber-attacks must be conducted along with actual conventional military operations. In the case of Georgia, the second one applies, as we had an ongoing military war following the Russian invasion.

The 2007 events in Estonia were a wakeup call for that nation, after which they took cybersecurity extremely seriously and became one of the leading countries in the domain. Students at the Tallinn University of Technology studied the Georgian case for cyber warfare and a book titled Georgia 1.0 was published. Yet even after 12 years, Georgia has not learnt its lesson.

Shortly after the 2008 war, the Georgian Computer Emergency Response Team discovered cyberattack incidents coming from Russian security services designed to collect sensitive and confidential information from Georgian and American sources. The malicious software, designed by Russian intelligence agencies, was able to steal documents and had features to take snapshots of desktops, activate webcams and gather collected data on shadow servers.

Starting from 2008 and still to this day, the Russians have used several approaches, including launching sophisticated attacks on specific websites or hosting providers, using satellite IT companies to retrieve sensitive information, spreading malware and especially Remote Access Trojan as a tool of cyber espionage.

Valuable experience

Cyber espionage, indeed, remains one of the main problems in the field. It is the most useful tool in the hands of criminals, intelligence agencies, corporate espionage, and even politicians and the media. These activities successfully gather information, fabricate facts and make an impact on certain informational campaigns.

Cyber espionage can provide a strong advantage both to governments and the private sector. Tools for spying are cheap, most of them are anonymous and very effective. Every intelligence agency is made to gather intelligence, be it classic human intelligence (HUMINT), signals intelligence (SIGINT) or cyber-intelligence (CYBERINT). We should not be surprised that these actions are conducted however we rather need to think about the new ways to counter these strategies.

Russia continues to attack and Georgia is still under occupation. Protracted conflicts have become a handy tool for the Kremlin to disrupt our development. Georgian citizens from regions near areas of conflict are under constant pressure, and hybrid warfare is as active as ever.

Cultural and economic expansion as a tool of Russian intelligence is exercised on a daily basis, and cyberspace is not an escape. A few months ago, the Russians attacked Georgia’s major hosting providers and more than 2,000 resources were defaced with the picture of the former president, Mikheil Saakashvili.

Both the political situation and the pandemic have given an upper hand to Russian intelligence services interested in spreading disinformation. For me, everything that happens in Georgia seems to be a cyber exercise, which, after calibration and prototyping, will be exported to the West and elsewhere. In essence, Georgia has become a test field for designing more sophisticated cyber and intelligence operations.

Today the international community is confronted with volatile, unpredictable threats. These challenges need to be faced adequately, and that is why now, more than ever before, there is a demand and dependence on information security and cybersecurity.