The dog that didn’t bark: The disappearance of the citizen

Identity politics in the USA, and what Europe can learn from it

Democratic citizens are not born, they must be made – but we are not doing a good job of this, writes Mark Lilla. As identity politics wreaks havoc in America, he challenges the liberal left to come up with a vision that embraces citizenship.

Anyone who was raised during the Cold War, as I was, was brought up with a strong sense that liberal democracy had external enemies. The Second World War had been fought against the fascists, and afterwards the Soviet Union, China, and their client states challenged democratic governments around the world.

This explicit assumption, though, was accompanied by an implicit one. We also assumed that once its external enemies disappeared, liberal constitutional democracies would flourish undisturbed and that perhaps democracy would spread to other countries. This assumption was less a product of arrogance than it was of a particular historical experience. My generation had never had to learn the lesson that liberals from the nineteenth century to Weimar were forced to learn. That liberal democracy is a very fragile system of government that always faces adversaries on the right and the left.

Why? In part, because the ambitions of liberal democracy, properly understood, are modest. It offers a way of conducting politics legitimately but does not promise a transformation of human existence or even of society. It also depends on building a capacity for self-government. Liberal democracy must take individuals whose prime concerns are naturally themselves, their families, or their religious or ethnic groups, and turn them into citizens. Citizens concerned – and sometimes primarily concerned – with the common good. My generation had never had to learn the old lesson that democratic citizens are not born, they must be made. Each and every generation.

Are we doing a good job of that today? No, I don’t think so. Many of the challenges our democracies face today can be traced, I believe, to our increasing inability to shape citizens, and then to give them voice. Consider three challenges in particular.

The first is neoliberalism, an ideology that has had a grip on our political imagination since the 1980s. The basic dogmas of this ideology are: (1) that we are fundamentally free individuals without natural or historical obligations to others, we are just elementary particles floating in space; (2) that economic wellbeing should be our overriding concern; (3) that markets – including labour markets – should be as free as possible to assure that wellbeing; and (4) that keeping markets free in a globalized economy means giving more authority to technocrats, and less to sovereign legislatures and the citizens who vote them into power. None of these dogmas address citizenship. And when put into practice they erode it.

This takes us to the second challenge to our liberal democracies, which is populism. Reaction has been brewing for some time to economic policies based on neoliberal dogmas. More and more Europeans and Americans feel that they have been denied a voice in determining their collective destiny. But the reaction to those policies is not taking liberal, democratic form. Instead, people have been drawn to populist parties that address them, not as citizens, but as the one and only legitimate people: das Volk, le peuple, il popolo. The voices one hears are not those of responsible leaders engaging with informed citizens. Instead one hears demagogues screaming and their mobs screaming back. And the message of both is quite simple: they want to ‘take their countries back.’ By which they mean that the unreflective and unmediated will of one part of the population must be taken as command.

These two challenges – neoliberalism and populism – are familiar. There is also a third challenge to our liberal democracies. It’s what I’ll call identity politics.

By identity politics I mean a way of conceiving of and engaging in politics that puts a premium on group identity or personal identity, rather than on one’s status as a citizen. It presumes that all political issues must be seen through the ‘lens’ of identity, as Americans say today. And in its strongest version, it claims that all appeals to citizens as citizens is really an appeal to one identity group against others. The effect of this identity consciousness on American politics has been disastrous. On the left it has induced a kind of moral panic about racial, gender, and sexual identity that has distorted the left’s core message and prevented it from becoming a unifying force in national politics. And in reaction to the left’s single-minded focus on identity, the right has benefited from the reaction of middle America to what they see as a political correctness that excludes them and their concerns.

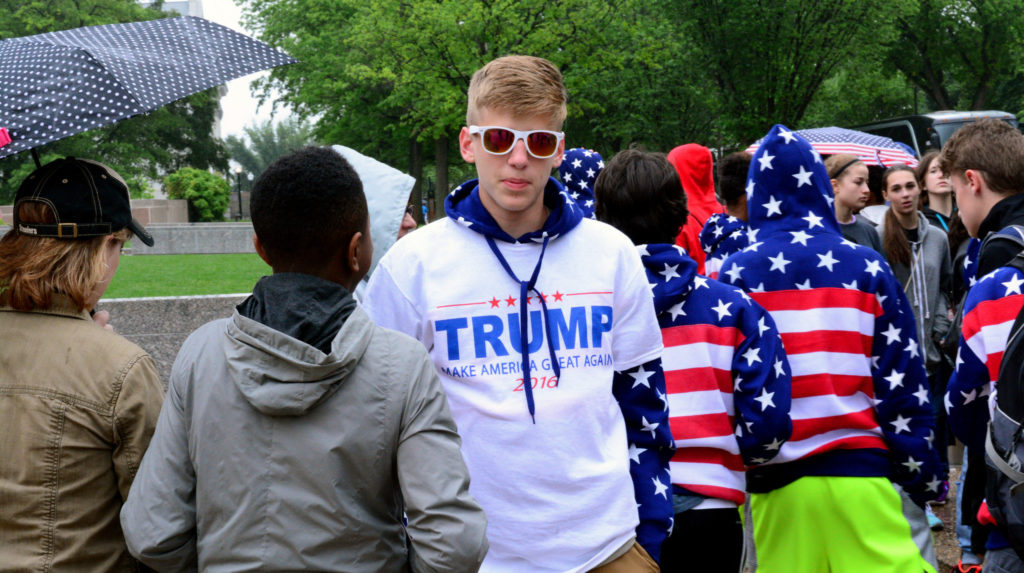

Photo: Juan. Source: Flickr

Now, a great number of factors contributed to the election of Donald Trump. But one of the most significant was the inability of the liberal left to provide a vision of America and its destiny as a compelling alternative to Trump’s vague demagogic slogan, ‘Make America Great Again.’ John F. Kennedy once famously challenged American citizens to ‘ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.’ Ronald Reagan spoke of ‘morning in America’ and of a ‘shining city on a hill.’ Identity politics has rendered the American left mute, incapable of using this kind of language to citizens as citizens for the common good. All it sees are groups or individuals, each which its own special identity. This is a very American story. But I think it also has important lessons for Europe.

The United States has always been a diverse nation open to immigrants. But it has not always practiced identity politics in the contemporary sense. It is true that with the massive immigration of Europeans in the decades just before the turn of the twentieth century, recent immigrants – Italian-Americans, German-Americans, Polish-Americans – did vote as blocs, especially in the age of machine politics in big cities. But they did so as ordinary interest groups, not to assert their ethnic identities or claim any special privileges or exemptions. The Polish neighbourhood voted for more jobs, the Italians voted for more parks, the Germans voted for more schools. And politicians tried to accommodate these groups in order to win their votes. But at the level of national politics, Italian-Americans, German-Americans and Polish-Americans argued and voted simply as citizens. And when it came to fighting in the two world wars, they served and died as citizens. That was their identity.

Things began to change with the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s, and for understandable reasons. African-Americans were obviously not ethnic immigrants, they had been slaves. They were not citizens forming a mere interest group, they were not even full citizens enjoying equal protection under the law. African-Americans found it nearly impossible to vote in certain parts of the country, schools were segregated, as were public facilities and businesses throughout the South. European immigrants had been able and eager to downplay their ethnic identities in order to assimilate into a white and largely Protestant America. African-Americans could not shed their identity if they wanted to. And so they were forced to mobilize politically around it to fight for their rights and become equal citizens. But this is the important point: their assertion of identity was not an end in itself. It was a means for achieving citizenship within a liberal democracy. Theirs was a political goal. And in pursuing that goal, African-Americans gave white Americans a lesson in citizenship.

Then things began to unravel, for many reasons: the disaster of Vietnam, the radicalization of protest movements against it, the rise of the counter-culture, which was also what one historian called the ‘culture of narcissism.’ But the most significant transformation was that the liberal left splintered into different identity groups in the 1970s, and then into smaller sub-groups, each demanding not just rights but social recognition. Black radicals broke with the staid, religious leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, preaching a kind of separatism and racial pride: Black is Beautiful. Feminists who felt they were overshadowed in the anti-war movement broke away and demanded rights of their own as citizens, but also recognition of their difference as women. Blacks and lesbians within the feminist movement then broke away, claiming that it was dominated by straight white women and their values. The male gay rights movement followed the same arc, from demands for equal rights, to demands for social recognition and affirmation, and then to internal squabbles over just what it meant to be authentically gay.

This story – of a left fracturing into smaller and smaller factions – is a familiar one in Western political history. But what happened next in the USA was unusual. As America became more conservative and individualistic in the Reagan years, the energy behind these battles over identity was directed away from the political arena, and was invested instead in our colleges and universities, which became theatres for an ersatz politics of identity formation and self-assertion. The primary question for the university left shifted from how to mobilize people sharing a certain identity to defend their rights through the political process – which is the work of citizens. And it became how to determine and assert one’s own personal identity: as white or black, male or female, gay or straight. The formation, cultivation and assertion of the self became the centre of attention in the narcissistic Reagan years. What had begun as a political project turned into a psychological drama – but with pretensions to political seriousness.

Why does all this matter for American democracy? It matters because universities are where the American liberal elite is formed today. It is where they first become conscious of their role as citizens, or do not. And it is where they first engage in politics, if they are going to engage. In an earlier era politically inclined students took courses in political history and political philosophy. They also would have had to grapple with Marxism. Marxism as an ideology had many faults but one large virtue: it forced those who adhered to it to look up from their particular situations and engage intellectually with the deep forces that shape history. Forces like class, war and colonialism. Marxists often saw things upside down, or saw ghosts, but at least they were looking.

Today, American students are encouraged to take courses that relate instead to their personal identities, however they conceive of them. And they are encouraged to think that this is what it means to be political engaged. They are drawn to courses on the literature of particular groups they feel affinities for: black literature, women’s literature, gay and lesbian literature, post-colonial literature. And instead of courses on the history of political ideas, they turn instead to ones on theories of racial and gender identity, heavily influenced by the mystical doctrines of French post-structuralism.

I have found that students who emerge from such an education make the following assumptions about politics: that group or personal identity, not citizenship, is the foundation of democratic politics. That an appeal to the nation as a whole is really an ideological cover for the domination of one group over the others. That discourse about political ends is always coded by identity, so that the notion of rational discourse among citizens as citizens is an illusion; that they have no obligations merely as citizens, only rights that must be defended from the perspective of identity; and that ordinary, electoral politics – which requires negotiation, compromise, and a lot of listening – is impure. They have little inclination to engage in party politics or run for political office. Their politics is expressive, not persuasive.

The point I wish to make is that the startling and appalling success of Donald Trump’s populism is not simply due to failed policies, or Republican tactics, or right-wing propaganda. It is also due to the liberal left’s inability to articulate a vision of America and its destiny that would rally all Americans, whatever their identities. It is also due to its indifference to the cultivation of citizenship even among those in its own ranks. The presence of certain factors has fuelled contemporary populism. But so has the absence of other factors.

And it is here perhaps that Europeans combatting populism may have something to learn from the American experience. The lesson is that you cannot create or sustain liberal democracy without creating and sustaining citizenship. This is very clear in Eastern Europe, where in many countries today you find formally democratic states but without, or with few, democratic citizens. After 1989 the cart (state formation) was necessarily put before the horse (citizen formation). It was assumed that once institutions were established they would automatically transform former subjects of communist states into citizens willing and able to govern themselves according to democratic norms. Instead, it created wealthier consumers, many of whom are now willing to leave the ruling to oligarchs and reactionaries who appealed to national identities. The same might be said of Western Europeans drawn to populism. There has been a patent failure to build citizens across Europe, and not least in relation to the European Union.

There is a Sherlock Holmes story called ‘The Adventure of Silver Blaze’ in which a horse trainer is murdered. Sherlock Holmes solves the case when he realises that when the killer approached, the victim’s dogs did not bark. This could only have meant that they recognised the killer. Holmes called this the ‘curious incident of the dog in the night-time.’ We have been witness to a similar curious incident in contemporary politics: that as a vicious populism has arisen to threaten our democracies, so many citizens have failed to bark.

Photo: Virginia State Parks. Source: Flickr

Published 18 August 2017

Original in English

First published by Transit 50 (in German), Eurozine (in English)

Contributed by Transit © Mark Lilla / Transit / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Voicing opinions to explain political tensions from afar is contentious for those treated as mute subjects. Focusing solely on distant, global decision-making disguises local complexity. Acknowledging the perspectives of East Europeans on Russian aggression and NATO membership helps liberate the oppressed and open up the debate.

A changing world

EU, USA, China

From COVID-19 to economic tensions and full-scale war in Ukraine, the relationship between the EU, the US and China has undergone seismic shifts since the last European Parliamentary elections in 2019. This year’s elections on both sides of the Atlantic are likely to alter these dynamics, changing the geopolitical landscape again.