The visions of an apocalypse peddled by nihilistic humanists and misanthropic transhumanists confuse the destruction of humankind with salvation.

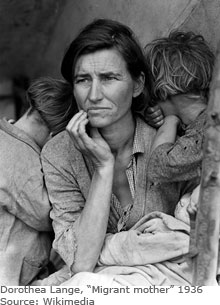

When Roosevelt insisted that photographers and writers document the Great Depression, they produced lasting, iconic work that allowed America to doubt its myths but also to get back on track. So where, asks Alice Béja, are today’s Dorothea Langes and John Steinbecks?

By early 2012, Wall Street liquidity had climbed back to pre-crisis levels, but unemployment, though falling, remained at an historic high for the United States (around 9 per cent for the year 2011). The Occupy movement’s mobilization of the “99 per cent” in Autumn 2011 exposed the inequalities that divide American society – and guaranteed their central place in the political discourse. Inequalities in the US are indeed greater than ever: in allusion to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s defining novel of the enchantments and delusions of the American dream, US government economists have started talking about the “Great Gatsby curve”. Measuring social mobility and income inequalities, it reveals that the US now has the most unequal society in the West.1 The trend didn’t start with the crisis, but the crisis has strengthened it, showing the tears in the American dream, through which one can see rows of abandoned houses and lines stretching out of soup kitchens.

What happens when a crisis undermines the very foundations of a nation and the stories it constructs for its people? Should the cracks be displayed, in order to raise awareness, or rather disguised, papered over to preserve the thread of the national narrative? The current crisis is often compared to the Great Depression that followed the 1929 stock exchange crash. The 1930s were characterized both by extreme economic difficulties (unemployment ran as high as 25 per cent) and by an extraordinary cultural flourishing that often found its subject in the crisis itself.

While Herbert Hoover, as president of the United States from 1928 to 1932, persisted in denying the real scale of the crisis (calling it a “depression” so as to avoid the word “panic”, which had been used to describe stock exchange crises of 1907 and 1913), his successor Franklin D. Roosevelt chose the opposite course of action: the depression needed to be displayed, alongside the government’s genuine intention to help out its victims. As a result, today, the first things Americans think of whenever the Great Depression is mentioned are photographs (by Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans), fictional characters (such as the Joad family in Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath) and song lyrics (by Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and Yip Harburg, author of Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? and Somewhere Over the Rainbow).

That crisis, which shook the very foundations of the country’s identity, has become an essential element of the way America sees itself. Today, a wholly new crisis once again casts doubt on the United States’ standing in the world; yet America’s dream factory is at a standstill, despite Obama’s attempts to reignite collective identification around historic landmarks and iconic representations of the nation.2

To paraphrase General Sheridan (“a good Indian is a dead Indian”), we could say that “a good crisis is a hidden crisis”, one that remains invisible, preserving the political and social consensus, and which affects only those who lack the means to make themselves heard. This, at least, seems to be what Hoover thought when the stock-market crash of October 1929 began to have consequences not only on the country’s banks but also on citizens’ living standards and chances of employment. In December 1930, Hoover was still insisting that the economy was “fundamentally sound”. While we should resist caricaturing his presidency (he introduced some reforms that would later be adopted by Roosevelt), it is indisputable that Hoover sought to play down the “depression”, to keep it invisible, hoping that the crisis could be brought under control without the whole country getting dragged in. But his story was rapidly demolished by the images flowing in from all four corners of the nation, causing him to be harshly criticized over his refusal to face up to reality. In 1932, for example, Fortune magazine published an article entitled “No One Has Starved”, referring to a speech Hoover had made about the living conditions of the unemployed. Illustrated by Reginald Marsh,3 the article described what were commonly called Hoovervilles – slums built by the jobless and homeless. Having attempted to hide the crisis, Hoover found his name associated with one of its most visible – and shocking – manifestations.

Triumphantly elected in 1932, Roosevelt adopted a radically different strategy. In fact, displaying the crisis to the country would become one of his presidency’s stated objectives, particularly from 1935 and what was known as the “second New Deal”. His objective was primarily political: highlighting the crisis also justified the exceptional measures taken to resolve it. In a nation whose political culture rested on the belief in small government and individualism, Roosevelt’s interventionism provoked great distrust; he had to convince the American people that the federal state could, and must, play a role in solving the country’s economic problems, even if that meant assuming powers that it had never previously had (creating unemployment benefits, controlling the financial system etc.). Culture now became a political tool aimed at creating nationwide awareness of the gravity of the crisis, at the same time encouraging a sense of national solidarity that would make the necessary responses more palatable. This explains the celebrated line from Roosevelt’s first inaugural address, in March 1933: “We have nothing to fear but fear itself.” He wanted to arouse the country from the torpor that had set in during the early years of the crisis (1930-1932), when unemployment rates had risen spectacularly and when banks had fallen like dominos (10 per cent of American banks went bankrupt between 1929 and 1931), and when every adult had begun to fear for their job, their family and their children’s future. Roosevelt also wanted to restore politicians’ credibility and to re-establish a connection with the people, which he did by means of his “fireside chats”, informal radio broadcasts where he would explain his policies to the country.

The government directed its efforts into two complementary projects. The first sought to sow culture in places usually out of its reach, by funding plays, concerts and mural paintings, to encourage American culture to go beyond its coastal heartlands (traditionally, cultural production has been concentrated around New York, on the East coast, and between San Francisco and Los Angeles, on the West Coast) and show “the people” that they too could have access to cultural production. The second New Deal investment project explicitly aimed to “show America to Americans”, as the head of Farm Security Administration, Roy Stryker, expressed it. The crisis must be documented, shown, embodied; a face must be given to those who were suffering, those who, to borrow Marx’s terminology, “cannot represent themselves” and “must be represented”. Writers and photographers were sent out onto America’s highways to plunge into the Great Depression and make it the subject of their works. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) funded federal projects in the visual arts (the Federal Arts Project), in music (the Federal Music Project) and in literature (the Federal Writers’ Project and Federal Theatre Project). Writers were commissioned to write guides to all the States of America, to collect the statements of the poor and black Americans;4 in short, to take part in a vast ethnographic and documentary project that would enable crisis-stricken America to know itself better. Richard Wright, Nelson Algren, Ralph Ellison and Saul Bellow were all employed by the WPA. The Farm Security Administration, meanwhile, assigned photographers the role of branding the faces of ruined southern sharecroppers into the minds of Americans. The most iconic of these images are without question the photographs of Dorothea Lange, especially the famous “Migrant Mother”. Of course, such investment was not without a political subtext; Pare Lorentz’s documentary The River (1938), for instance, showed the scale of the government’s efforts, such as the works undertaken by the Tennessee Valley Authority to restore economic dynamism to a region severely affected by the crisis.

The government directed its efforts into two complementary projects. The first sought to sow culture in places usually out of its reach, by funding plays, concerts and mural paintings, to encourage American culture to go beyond its coastal heartlands (traditionally, cultural production has been concentrated around New York, on the East coast, and between San Francisco and Los Angeles, on the West Coast) and show “the people” that they too could have access to cultural production. The second New Deal investment project explicitly aimed to “show America to Americans”, as the head of Farm Security Administration, Roy Stryker, expressed it. The crisis must be documented, shown, embodied; a face must be given to those who were suffering, those who, to borrow Marx’s terminology, “cannot represent themselves” and “must be represented”. Writers and photographers were sent out onto America’s highways to plunge into the Great Depression and make it the subject of their works. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) funded federal projects in the visual arts (the Federal Arts Project), in music (the Federal Music Project) and in literature (the Federal Writers’ Project and Federal Theatre Project). Writers were commissioned to write guides to all the States of America, to collect the statements of the poor and black Americans;4 in short, to take part in a vast ethnographic and documentary project that would enable crisis-stricken America to know itself better. Richard Wright, Nelson Algren, Ralph Ellison and Saul Bellow were all employed by the WPA. The Farm Security Administration, meanwhile, assigned photographers the role of branding the faces of ruined southern sharecroppers into the minds of Americans. The most iconic of these images are without question the photographs of Dorothea Lange, especially the famous “Migrant Mother”. Of course, such investment was not without a political subtext; Pare Lorentz’s documentary The River (1938), for instance, showed the scale of the government’s efforts, such as the works undertaken by the Tennessee Valley Authority to restore economic dynamism to a region severely affected by the crisis.

While supported and financed by the government, this documentary drive, which was born of a genuine need for representation, was contributed to by the illustrated magazines, which were at the height of their popularity at the time, as well as by local and national newspapers, which looked for articles on “social” topics. It was for the San Francisco News that John Steinbeck began to write about the “Okies”, sharecroppers forced to leave their holdings in the central United States (Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico – the region labelled the “Dust Bowl” for the dust storms that plagued it) in the mid-1930s, to try their luck in California. These articles5 were to become Steinbeck’s main inspiration for The Grapes of Wrath. Similarly, when the writer James Agee and the photographer Walker Evans were sent by Fortune magazine to document the lives of poor peasant families in Alabama, their study – which Fortune refused to publish at the time – resulted in the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, published in 1941,6 which today belongs to the canon of Great Depression classics.

Why were politicians and artists so keen on depicting the Great Depression, on giving it representation, a face and body? Was it simply a political move on the part of Roosevelt? And for the writers, artists and photographers, was it simply a way of earning a living in hard times and of fortifying leftist notions associated with the Popular Front?7 These motivations should not be dismissed, but they cannot alone explain the staggering impact that these projects had on popular culture and even on America’s collective consciousness.

The Great Depression was much more than an economic crisis. It called into question the fundamental precepts of American identity underlying the boom of the 1920s (the “crazy years”), which had strengthened America’s position as a world power gained during the First World War. Individualism, the spirit of enterprise, mobility, the pursuit of happiness, the fiction of a classless society – the foundations of the national narrative were suddenly shattered by the scale and gravity of the crisis. How could people believe in success when a quarter of the population was unemployed? How to be sure everything would be all right when you are reduced to wandering from town to town, jumping on and off freight trains? The “American dream” had become an illusion, and more and more people no longer saw individualism as the way forward. In this, they were in agreement with their president. Indeed, instead of calling on the jobless to pull themselves together, instead of making every individual responsible for his or her own plight, Roosevelt, taking stock of what was happening, spoke out against the race for profit and material wealth. He highlighted the importance of national solidarity, calling for the creation of a “new economic order”.8 The time had come for a genuine, brand-new national consensus. Arguments aside over whether Roosevelt effected lasting changes on Americans’ conception of their federal government, it is clear that contemporary images of the Great Depression played their part in an impulse to re-imagine the narrative of ineluctable progress that characterized political rhetoric and the entire story of America.

Why have the faces of those southern sharecroppers become the image, the icon, even, of the crisis of the 1930s? Why they and not the small shareholder, that typical figure of the 1920s, when shares were sold on to a broad sector of the population, having long been held by an elite of professionals and experts? After all, the small shareholder was also ruined by the 1929 crisis. Moreover, the farmers had been in crisis since well before 1929 – the 1920s had already been hard on them. Like black Americans, they had been left behind by the boom. And, in many respects, the middle classes were worse affected by the crisis, in the sense that their living standards were, perhaps, more radically altered. Nevertheless, it was those emaciated bodies, those hollow faces with their sunken eyes, the ragged overalls of the sharecroppers, that recurred throughout the works of Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White, Walker Evans, John Steinbeck, Erskine Caldwell and James Agee. It is their decrepit shacks, the wagons on which they stacked their whole world, their shyly smiling children, whom we meet, returned to life by every sentence in the novels and through every photograph. Why? Because they are the anti-American dream. They represent the alternative history, the story no one wanted to tell, one that for years was being written between the lines of the national narrative, which until then could only harp on about progress.

Mobility? The pioneer spirit? In these images, all migration is forced. In Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, the Joads leave their land after being dispossessed; in his first novel, Nelson Algren describes the life of a young man who has become a hobo, reduced to living on the street by poverty and violence.9 It is no longer a question of conquest but of survival. It is no accident that John Dos Passos’ great trilogy, U.S.A., opens and closes with the figure of a wandering man. The young man in the preface is open to all opportunities, greedy for sensations (“One bed is not enough, one job is not enough, one life is not enough”10), but the tramp with which the last volume ends has realized that the promises were nothing but delusions: “With swimming head, needs knot the belly,”11 while above him, in the air, a transcontinental passenger with a full stomach and a full wallet looks down on a country he knows belongs to him.

How are we to explain that individualism, so central to the “American spirit”, has ended up as its caricature? In the art of the 1930s, this too is challenged. Just as Roosevelt tried to revive his country by appealing to a sense of community, artists were determined to transform the protagonist facing his fate alone. America’s trade unions, political parties and, above all, its families, stormed into its fictions. The individual no longer reigned supreme and from now on could survive only when supported by his or her kin. The best-known example is, of course, the Joads in The Grapes of Wrath: Ma Joad, in particular, stands for continuity, the endurance of a certain idea of family and the people (her final line in the John Ford film version is, “we are the people, and the people go on forever”12).

Throughout these works, America tells its story, unmasks itself, displays its saddest and most desperate face; we are shown America’s poor, “condemned to invisibility and anonymity, links in the infinite chain of generations that reproduce and die”.13 The desolate lands of the Dust Bowl are the antithesis of the New World, the land of milk and honey envisaged by the Pilgrim Fathers. The American pastoral, the dream of prosperity and harmony with nature, is blighted by the crisis. Yet, out of these depths, out of this re-writing of the national narrative through the story of a family of poor farmers, there emerges a new sense of hope. This hope is channelled through the figure of Tom Joad, who grows into a defender of the oppressed; through the beauty of the photographs of Lange and Evans; through the endurance of songs by Guthrie, nicknamed the “Dust Bowl troubadour” (he wrote a song about Tom Joad, who also features in a work by Bruce Springsteen). The need to represent the crisis displaces the myth, rewrites it. It allows the country to doubt its myths but, as Pierre-Yves Pétillon has argued, also to get back on track: “For America, telling the story of its origins is itself a dynamic device, the outline of a ‘trajectory’ that Americans must continue, perfect and follow; each time it steps backwards, this can only be in order to push forward once more.”14

Charles Baudelaire recommended crushing the poor in order to allow them to regain their dignity and their humanity.15 The America of the 1930s, led by Roosevelt, exhibited the poor, put them on show for the entire nation to see. Some criticized this display, claiming that the country was thereby debased along with its miserable, manipulated poor. All the same, America remembers these images, not simply out of pity or horror, but as an integral part of its history. Hardened, but often resolute faces, engraved in the collective imagination.

Does this mean that, today, Obama’s government should send artists out onto the streets? The context is quite different, as are Americans’ expectations of politics. Certainly, Tea Party activists would have much to say about any public money being spent in this way. But must we give up on all representation of the crisis? The activists of the Occupy movement, for their part, have thoroughly understood that the crisis must be made visible, responding to evictions by an occupation of public space. While there is, as yet, no iconic representation of the 2008 crisis, there is no doubt that the tents of Zuccotti Park caught the public imagination, as did the Guy Fawkes masks that popped up here and there, manifesting the invisibility and anonymity of the victims of the crisis, as well as their ghostly presence. Once more, the American dream has been tarnished. Once more, political discourse is trying to knit together the scattered threads of the national narrative. In his speech at Osawatomie in December 2011, Obama chose to drop the individualist line in favour of a more collective vision of America’s mission: “As a nation, we’ve always come together, through our government, to help create the conditions where both workers and businesses can succeed.”

That “always” clearly looks back to the Great Depression. Yet, for now at least, his story lacks foundations in the imaginary.

E

Claire Gatinois, "Le déclin du rêve américain" ("The decline of the American dream"), Le Monde, 29 February 2012.

For example his Osawatomie speech of 7 December 2011. Obama chose the town of Osawatomie in Kansas for its connection to a speech Theodore Roosevelt gave on American values at the beginning of the twentieth century. Obama also peppered his speech with references to Franklin Roosevelt and the solidarity programme he set up in America during the Great Depression.

Reginald Marsh (1898-1954) was an American painter and illustrator in the realist style, known particularly for his images of the Bowery, in New York, and of the popular beach at Coney Island.

See Studs Terkel, Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression, 1970.

See John Steinbeck, "The Harvest Gypsies".

James Agee, Walker Evans, Let us Now Praise Famous Men, 1941.

A number of works produced during the second half of the 1930s were later labelled naive propaganda and excluded from the canon when, following the Second World War, scholars tended to prefer an idea of artworks as autonomous entities rather than as products of a period.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, "State of the Union Speech" of 4 January 1935. See also the passage in his inaugural speech of March 1933, in which he denounces bankers and financiers, comparing them to the money changers in the Temple.

Nelson Algren, Somebody in Boots, 1935.

John Dos Passos, U.S.A., 3 vols. 1938.

Ibid.

Line spoken by Ma Joad in the middle of The Grapes of Wrath, 1939.

Jolle Stolz, "Le roman de la crise. 1936. Hallucinant voyage chez les métayers de l'Alabama" (The crisis novel. 1936, Incredible journey among the sharecroppers of Alabama) Le Monde, 14 August 2009.

"À l'ombre de l'Europe" (In Europe's shadow), interview with Pierre-Yves Pétillon, Esprit, November 1986, 63.

Charles Baudelaire, "Assommons les pauvres !", le Spleen de Paris, in Oeuvres complètes, I, Paris, Gallimard, coll. "Bibliothèque de La Pléiade", 1975, 357-359.

Published 29 June 2012

Original in French

Translated by

Sophie Lewis

First published by Esprit 6/2012 (French version); Eurozine (English version)

© Alice Béja / Esprit / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

The visions of an apocalypse peddled by nihilistic humanists and misanthropic transhumanists confuse the destruction of humankind with salvation.

Voicing opinions to explain political tensions from afar is contentious for those treated as mute subjects. Focusing solely on distant, global decision-making disguises local complexity. Acknowledging the perspectives of East Europeans on Russian aggression and NATO membership helps liberate the oppressed and open up the debate.