‘…all calamities, misfortunes, and diseases flew out at once and plagued the entire human race. Pandora, frightened, quickly shut the lid, yet remaining in the box was but one Hope.’

The History of Ancient Greek Literature

‘There’s a cat in our courtyard, he looks like Hitler, he has the same kind of whiskers. We’ll call him Putin.’

Once a day a plane flies by. Close to the ground. It’s one of ours.

Nadia leaps out of her room. ‘It’s not coming towards us, is it?’

We cannot get used to this.

‘Is there a cellar here? Is it deep? And sturdy?’

Nadia waited ten years to watch horror films. A lot of her friends had already seen A Nightmare on Elm Street. One had even seen Tusk. Another Raw. I stalled, I slipped her Ghostbusters, Gremlins, not real horror films. She wasn’t satisfied.

On the 17th February Nadia turned ten. On the 19th she celebrated with friends at a dolphinarium, her impressions lasted for the next few days. On the 24th the war began.

In Poltava, after having spent a month under shelling in Kharkiv, Nadia appealed again. She insisted. It was now okay, I decided. She wanted to see The Ring – it turned out not to be frightening. The Ring Two was even more disappointing. In secret, unknown to me, she watched Pet Sematary, which I’d described to her as the most terrifying horror movie of my childhood. She didn’t find it frightening. We made a list. I remembered what I could: The Howling, Video Dead, Hellraiser, The Exorcist, The Shining, Wrong Turn, Friday the 13th, Scream. And thirty more horror films. I worry that these, too, won’t make an impression on her. I have nothing to offer her. The time of horrors is already behind us.

Now we watch cartoons on Netflix. The Sea Beast. The girl in the cartoon is also ten years old. She’s a mischief-maker, a girl-pirate. Harpoons fly like rockets. Guns like javelins. About the captain who went off to war, Nadia says, ‘like Putin’. All cartoons will probably be like this now.

Cinema makes no impression on me either. Before the war I watched serials every day. Good ones. I took pride in following what was going on, in keeping up with everything new. I shared my thoughts with my serial-addict friends. I wrote about the serials in glossy magazines.

I’ve stopped watching. With the arrival of the war, movies and tv shows lost their appeal. My wife signed up for Netflix. For a long time I looked around for something or other. To no avail, it was futile. The final season of Better Call Saul is good – but it didn’t move me. I started and abandoned 1883, the prequel to Yellowstone. I haven’t followed a single serial. Instead of films there are newsfeeds. Here, though – as my mother says – we are the ones captured on the screen.

I read a newsfeed, I tell Nadia about a game where children get rewards for geolocation. I ask her: have you come across this? She’s come across something else. On Instagram she was offered 100 dollars for the geolocation of our military sites. She sent the geolocation of Red Square. They answered: ‘Just hold on.’ They never paid.

Nadia washes cars in the parking lot next to Silpo. How much will people pay? Maybe twenty hryvnia.

‘A lot of the girls from our courtyard are doing this.’

I don’t know what to think about that. The war has changed everything. Including Nadia. She’s grown up quickly.

The locals teach them to just live, without being afraid of airplanes and air raid sirens, while the displaced persons have their own accounts to settle with Putin. It all mixes together wonderfully.

Blue Whale has returned. Fifty tasks, the final one being suicide. The first – draw a heart on your wrist with a red pen. The second – draw a blue whale on a piece of paper. The third – draw it on your leg. The fourth – cease to communicate with everyone. The fifth – run around your home several times. The tenth – carve a blue whale on your hand with a blade. The thirty-ninth – run across the street in front of a car.

Everything is filmed, the videos are to be sent to ‘Blue Whale’ on Telegram, at 4:20 am. It’s an inopportune moment for Blue Whale to have returned. At 4:20 am either people are sleeping or an air raid siren has gone off. Children write to Blue Whale: ‘Say Slava Ukraini! Glory to Ukraine!’ Blue Whale doesn’t answer. In 2018 he was on VKontakte.

I ask whether kids are playing war games in the courtyard, like we did when we were kids. Whether it’s ‘us versus the Russians’ in these games. In my childhood it was ‘us versus the Germans’.

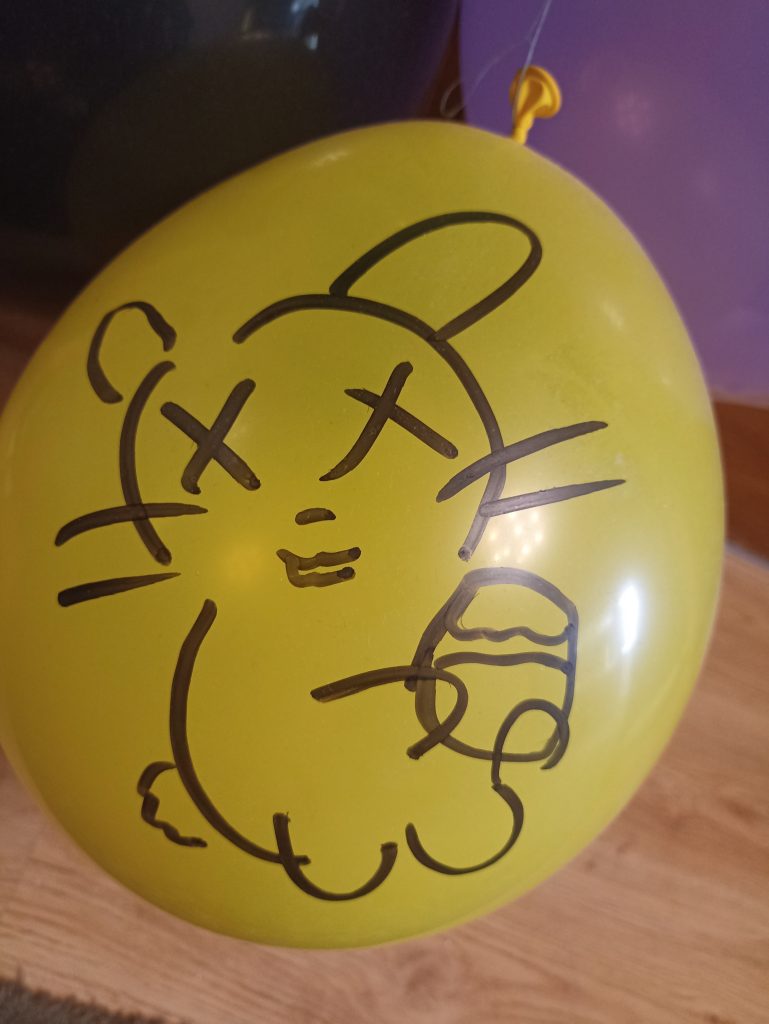

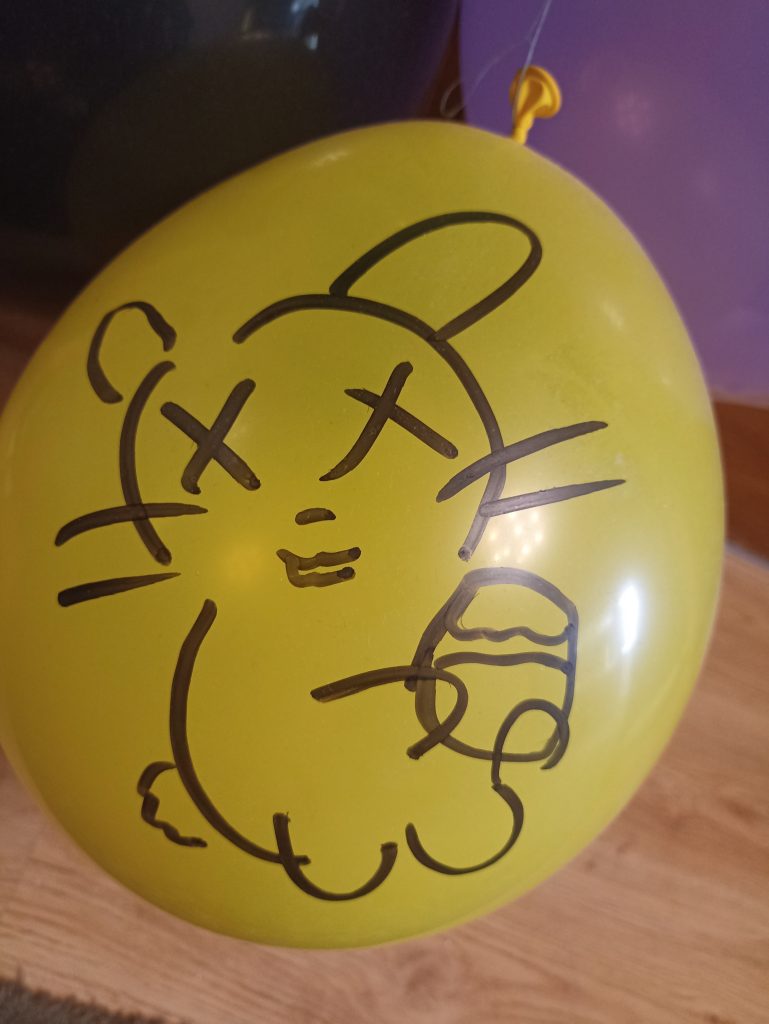

We make drawings on balloons left over from a celebration. We draw emotions: fear, sadness, hopelessness. Nadia manages well for a while. I make it more complicated: Uncertainty. Indifference. She thinks it over and figures it out. It’s recognizable.

I, too, am thinking it over.

‘Appeasement.’

She thinks for a long time, then, quickly, draws a hare with crosses on its eyes and something like a jar in its paws.

‘. . .?’

‘He died of jam!’

Author copyright

Nadia dreamt again that the war ended. This time Zelensky brought her the news. He came himself, in person.

‘He opened the door and said it.’

‘The door wasn’t locked?’

‘You remember when I dreamt that Lenochka came to visit us? And she came that same day.’

‘You also dreamt that the war ended.’

‘But that time Zelensky didn’t come.’

‘Nadia, they destroyed ‘the Hearth.’’

‘. . !’

‘The high school.’

‘Oh. . .’

In the sense of, a pity it’s not their school, the elementary school. But that’s just their way of joking. The reality is this: ‘Hello Irina Ivanovna! Thank you so much for these four years of school! You were the best teacher ever! You explained things so well! The whole time you were the nicest teacher! Thank you so much for what you taught us and for these years! I miss you, and I really hope we’ll see each other after the war!’

School is the teachers. Irina Ivanovna is homeless. Her home was bombed. She’s staying with a friend in Kyiv.

‘Good morning, students! We’ll meet online on Mondays at 11 am. All summer. And tell one another how we’re doing and what’s going on. Okay?’

Nadia has never liked to read. I have to negotiate, force her. We choose what might be interesting. Not this book, or this one. And not this one.

‘Which one then?’

‘The interesting books stayed in Kharkiv.’

At home she speaks in Russian. We all speak in Russian. I learned that in the courtyard they speak in Ukrainian.

‘Well, in Russian-Ukrainian. In surzhik.’

She asked me to give her a book in Ukrainian. She’s reading it.

Nadia’s grandmother gave her a jar of red caviar.

‘Yay!’

She hasn’t eaten caviar in a long time.

‘It reminds me of Kharkiv.’

She misses the toys she left behind in Kharkiv. Her grandmother brought her one of them, a shark from IKEA.

She hugged the shark and sniffed it.

‘It smells like Kharkiv,’ she says.

Last night there was another rocket attack. A video of a flying rocket was posted on Telegram. When she saw it, Nadia told us that on the 24th of February, in the evening when we crossed the whole city to get to where her grandmother lived, she’d seen a rocket like this flying above us. We hadn’t seen it. And until now Nadia had never mentioned it, she’d forcibly forgotten.

When we return home, all her things will have to be thrown out or given away. She’s grown up. The new things, too, given to her for the holidays, and for her birthday on the 17th of February. A week afterwards we left home traveling light: documents, a box with a cat. We thought we’d return in a day or two, that it would all be over.

On Telegram there’s a story about a dead kitten. It was lying in a child’s bed. Forty-five days without its owners. And a photograph. At least Nadia didn’t see the photograph.

But she knows.

‘What a good thing that we took Lotta.’

And to Lotta: ‘We’ll never abandon you.’

I think: ‘What a good thing that we took you away from there.’

‘Four hundred and eighty children have been killed in Ukraine since the beginning of the full-scale invasion,’ the media informs us.

Lotta – in honour of Lotta, The Children of Noisy Village by Astrid Lindgren, her favourite book, was left at home. I’ve never read it. It didn’t exist in my childhood. We had different books then, different films. Now my childhood heroes have turned against me, the stars of these films declaring themselves for war against Ukraine. Little Red Riding Hood. Elektronik, too. D’Artagnan, Kharatyan. Cheburashka – they say – is the secret to the Russian soul. Nadia has different films, different books. She will not be forced to break up with dead fairy tale heroes. Her childhood will not betray her.

A child has had limited life experience. She is being formed right now, and war, it turns out, is doing the forming. Nadia has changed so much during a year of war, she’s grown up very quickly. She’s been transformed from a child into an adolescent. All Ukrainian children have matured so much during the war.

Everything is about the war. A child is eating shawarma during wartime. On the packaging it says, ‘For Mom,’ ‘For Dad,’ ‘For the Armed Forces of Ukraine,’ indicating how much needs to be eaten for whom. Тhe shawarma – in Poltava slang shavukha – tastes good.

Nadia created an installation for her mother on her birthday. Lena had told her what she wanted as a gift: ‘Putin’s head.’ Materials: salt dough, gouache, combed cat fur. A Ukrainian flag – a plastic stick – inserted into the ears. Putin’s face has a surprised look. It looks very much like Putin.

Author copyright

Nadia painted a picture. The canvas cost 100 hryvnia at a discount store. The corners were worn. It would normally have cost 150. A gift for Larisa, the owner of the apartment. A landscape, no people, trees. Oaks, bushes – very realistic. Very realistic clouds. A blue sky, she didn’t spare the paint. A ghostlike swing, a road and something else related to people. The paint must have been running out. In the corner she signed the painting. She wrote ‘Nadezhda’ – and the year ‘2022’.

Author copyright

‘Dad? Dad, in the spring the lights won’t be shut off?’

‘No. They said it was over, the situation was under control. Although this is Russia – they’ll come up with another nasty trick.’

‘I know. But we have to be happy about something.’

Yes, yes, yes, children do have to be happy about something. Children and cats – the central heroes of our whole story. For me. The elderly are stubborn, adults fuss, children and cats accept everything as it is, taking it into the system of their life.

Photographs of Kharkiv. In someone’s window an icon, in someone else’s window the pasted words ‘GO FUCK YOURSELF’. Most often there are no windows; they’re covered with plywood.

I’m calm. Before the war everything made me nervous. Lectures. Trips. Work. They recast my texts in the journal Kharkiv – Where, When, What. I was unnerved, furious. For days, weeks I was overwrought. I wanted justice, and revenge. The day before a lecture I would start to get anxious. An hour before a lecture everything would tremble, my blood pressure would go up, I’d feel dizzy and sick.

A month under shelling cured me. I found myself in a stupor, terrified – and then the fear quieted down. Today I don’t worry about any of this. I worry about my parents, problems at work don’t touch me. I give lectures in Ukrainian, improvising at every step. In a terrible surzhik. It doesn’t bother me. My lectures in Russian, the sheets of paper, have remained at home. I’m here, I’ve survived, neither the future nor money concerns me. The university didn’t give me holiday pay, reduced my status to part-time, didn’t pay my salary for half of September, sent me on unpaid vacation. It’s all the same to me. I tried to be indignant, to work myself into a state, it doesn’t interest me. Just living interests me. I enjoy the cat, who enjoys me and who purrs. She, too, was in a stupor for a long time, unable to eat or socialize. I like to walk the streets, to see people. My daughter is growing up, she’s dyed her hair and cut it short. She looks like Alisa in Guest from the Future. (‘Alisa, will the future be fun?’ – ‘Yeah, it will be fucking awesome.’) I enjoy the thought that I’m still alive. Nadia likes school, she likes her lessons, although she doesn’t admit it. I listen as she gives answers in the next room, I see her preparing for her classes. She was assigned a story to write in Ukrainian.

One day the city, and the state where the city was located, were attacked by a neighbouring country. The neighbouring country shot rockets, fired from tanks, bombed from airplanes. And all the children in the city were forced to go down into basements and cellars. They sat there for a week, two weeks, three weeks, a month and longer. Without sun and without playing outside they became sadder and sadder and didn’t want to talk to anyone. Neither with their parents, nor with their friends. But each child had a cat. Furry, soft, the cats purred at the children, calming them down. The children talked only to the cats. When the war ended and the children came out of the cellars, it turned out that each child had a cat who’d saved them. Everyone in the city found out about this and built a monument to the cats and put bowls all over the city and poured milk into them every morning. Since that time the tradition has been preserved and cats are respected by everyone.

The cat nibbles my hand, she wants to play. I play with her.

2022

Translator’s note: the name ‘Nadezhda’ means ‘hope’ in Russian.