The memory of feminism in East Central Europe after 1989 is blurred by the widespread fear to use the term radical feminism – which refers to demands of a deep-rooted social transformation to eliminate the oppression of women in every sphere of life and on every level of society. Gender mainstreaming and post-feminism have largely taken the place of a fight for women’s rights and the talk about women as such – a process that has unfolded in both East and West, but which, curiously, is often seen as an ‘eastern’ problem in the West and a ‘western’ one in the East. When it comes to the interpretation of 1989, a generational clash among feminists complicates not only the process of remembrance but also the future of a feminist movement – beyond boundaries.

The encounters between women from East and West in the Northern hemisphere after 1989 have been full of negotiations, productive exchanges and at times, misunderstandings. They have been the subject of much scrutiny too, scholarly, personal and political alike. For some, these encounters meant the ‘arrival of feminism’ to Eastern Europe. For others, what took place in the East was rather a return to the interwar traditions of feminism silenced by the establishment of the state socialist regimes. For others, the same processes appear as a happy reunion between East and West. There are also those who think the state socialist period represented a specific form of feminism and therefore question the importance of the post-1989 encounters or view them as little more than the colonialization of the East by the West.

The Yugoslav feminist prehistory

In order to understand what 1989 meant for feminism in eastern and east central Europe, and to place it between East and West, we need to turn to Yugoslavia. Here, we find an early case of East-West encounter, something that we may even want to a call a prehistory to what follows after 1989. Just like women in the rest of east central Europe, feminists in the second Yugoslavia were inspired by the ‘Western second wave’. It was a small but prolific, creative and brave feminist group that in the 1970s offered a possible reinterpretation and articulated a harsh but constructive critique of state socialist women’s emancipation. These women wanted to live in a state that finally took women’s equality seriously. This rare case of feminist dissent under state socialism grew out of a creative encounter of ideas, discourses and people between East and West. The Yugoslav feminists saw the potential in the knowledge production of Western feminists and thought that while Yugoslav socialism held the chance to liberate women, it was severely lagging behind its promise. They created an original version of feminism in Yugoslavia during the 1970s and 1980s, building on contemporaneous intellectual discourses, such as the Marxist revisionism of praxis, the Frankfurt and the Lukács Schools, while realizing the insufficiencies of these, just like of the official Yugoslav discourses and politics.

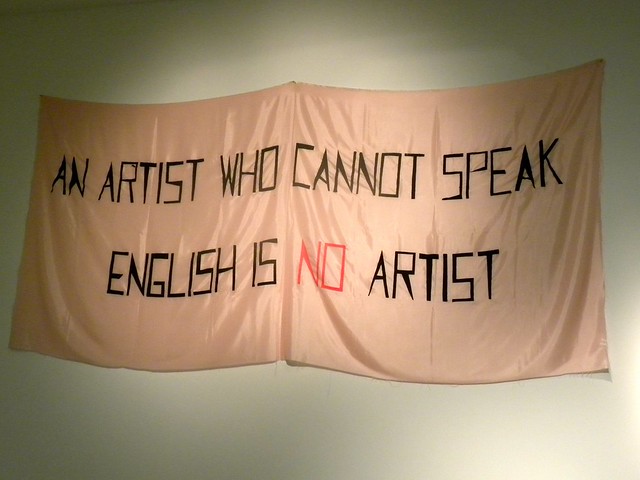

Sanja Iveković, Sweet Violence. 1974.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Jerry I. Speyer and Katherine G. Farley, Anna Marie and Robert F. Shapiro, Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis, and Committee on Media and Performance Art Funds. © 2011 Sanja Iveković

Photo via Moma.org

Yugoslav feminists were not trying to catch up with the West. What they understood from their readings was that the West was far from great for women, and feminism was needed to make life better for them in East and West.

In the meantime, while the dialogue between East and West was a highly productive one, the other opposition groups in Yugoslavia were mainly blind and often hostile to feminism – rather similarly to the post-1989 situation.

The feminist struggle for the elimination of violence against women provides a fascinating case study of East-West relations, geopolitical hierarchies and post-1989 continuity. Although it is a widespread phenomenon, it was radical feminism in the 1970s that brought attention to the systemic violence against women stemming from patriarchy. The women in Yugoslavia learned about the ideas and methods of tackling this through travels, study abroad programmes, and then through exchanges between women in Belgrade, Ljubljana, Zagreb and beyond. They were predisposed towards these ideas due to their familiarity with other radical critiques of oppression, such as democratic psychology and anti-psychiatry. Whereas the initial methodology came from the West, it was their understanding of local realities that made the work of women from Yugoslavia truly relevant. It was a country where the East-West interactions among feminists were most fruitful already before 1989, and yet the country soon plunged into disaster. Moreover, this disaster confirmed many of the feminist theses about patriarchy, suddenly making their theoretical framework and their anti-violence activism extremely relevant. When in the rest of eastern Europe feminists were trying to find their path amidst a transition discussed and decided upon by men, their sisters in arms in the successor states of Yugoslavia had to find a way to stand up against new oppressive regimes entering wars. So it would seem that there was a deep divergence, yet we can notice many similarities. Moreover, feminists in the countries of east central Europe now entered a similar type of negotiation with the West, encountering uncannily similar issues to those the Yugoslav feminists met with before them.

Post-1989 East-West encounters

While Yugoslavia was an exception in Eastern Europe with its coherent and early feminist activities, the history of feminism elsewhere in the region is much more closely tied to 1989. Hungarian feminism is but one illustrative example of the processes in east central Europe (and one with which I have more first-hand experience). As in Yugoslavia, the first feminist discussions occurred before the transition. In the late 1980s, the circulation of feminist ideas in the English and American Studies departments at various universities, especially in Szeged, Budapest and Debrecen, led to the emergence of informal feminist groups. The rapid dismantling of borders, the circulation of various publications, and new possibilities for civil society after 1989 facilitated an outburst of interest in feminism among the middle class intelligentsia, including readings, discussions, and the creation of explicitly feminist organizations. The establishment of the first feminist network (the Feminista Hálózat) was followed by the creation of the SOS helpline run by NANE (Women Against Violence), operating continuously since 1992. Women from the pre-existing Yugoslav helplines travelled to Budapest to offer their knowledge and provide the first trainings. The connection was established to a great extent thanks to the mediation of Antonia Burrows, who travelled across the region both to share her insights and to learn about local feminist initiatives. She was certainly not alone: many women, mostly radical feminists from various countries wanted to learn and share their knowledge after the lifting of the Iron Curtain.

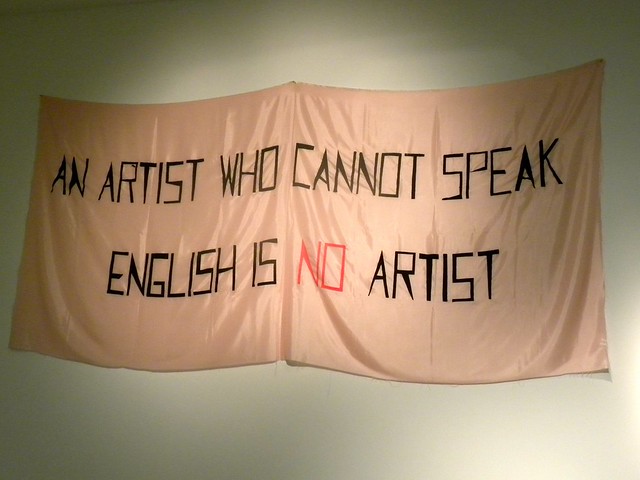

Many women at the (kitchen)tables in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland and elsewhere were confronted with feminist, especially radical feminist ideas for the first time. These encounters did not always prove easy. It was not just the Iron Curtain that had separated them for decades that the participants in these exchanges had to overcome: there was also a cultural and economic gap dividing them. It was the putative victors of the Cold War and the putative defeated side sitting down to a shared (kitchen)table to exchange ideas and experiences. As a recent book on GDR scholarship after reunification shows, intellectuals in east central Europe had to realize that after 45 years of – even if not hermetic but still heavy – intellectual isolation, Western academics viewed the knowledge they had produced as outdated or even dusty. Their English was supposedly not good enough either (recall Mladen Stilnović’s famed work, An Artist Who Cannot Speak English Is No Artist), their theoretical framework not up-to-date. And they were not even heroic dissidents struggling against an oppressive regime any more.

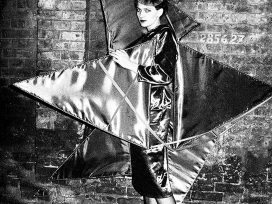

An Artist who Cannot Speak English is no Artist by Mladen Stilinović, 1992. Photo by JasonParis from Flickr.

These shocks were topped by the claims of radical feminism that patriarchy harms women (and men too, even if to a much lesser extent) in every single sphere of their lives. That patriarchy kills women. That as a woman it is nearly impossible to ‘have it all’, and that women end up as victims of patriarchal dynamics. The women hearing these claims on the eastern side of the table, some of whom would then found anti-violence groups while others would soon become the first professors of gender-focused scholarship, were forced to rethink their entire lives, re-evaluate relationships, friendships, and life choices. Moreover, they were not protected by the pride that the Yugoslav feminists possessed in the 1970s, living in a self-managing socialist regime that still held high promise for them as an exceptional and supposedly successful alternative to the Soviet model as well as to the capitalist West. It can be extremely challenging to face the fact that one remains oppressed when people thought that their oppression had just ended, only to be told by others, perceived as the winners in the Cold War, that their oppression is to continue. A hard and complex process of understanding, invention and implementation followed these difficult encounters.

And yet, these exchanges were not just alienating, they were also inspiring and liberating. What actually happened contradicts a set of interlocking stereotypes that ‘eastern’ women were simply not ready for feminism; that as a consequence, western feminists and their NGOs started to dictate what feminism in Eastern Europe should be; or that the result was a liberal version of feminism which essentially functioned as a handmaiden of neoliberal capitalism. This is an inaccurate generalisation of the experiences of many women and the actual diversity of feminism in post-1989 East Central Europe, let alone in Yugoslavia and its successor states.

Several trends are discernible within the significant diversity of countries, organizations, individuals, and generations. The 1989 generation’s feminism, with the anti-violence groups, academics and intellectuals, has indeed heavily impacted the feminist agenda in the region, even if theirs was not a particularly well-defined agenda. The feminists of the 1989 generation were largely well educated, economically independent, and could be critical of both old regimes and new ideas. In academia and activism alike, feminists in eastern Europe were encountering a multitude of ideas, mostly coming from the western ‘second wave’ and its aftermath. However, this was far from following some kind of ‘western orders’ alien to the local context. As Judit Wirth, one of the most unique creators of Hungarian feminism over the past two decades recently said in one of her lectures: ‘we chose to work on violence against women, because we thought it was important’.

The prevailing liberal ideological framework in east central Europe after 1989 both opened up some possibilities and foreclosed others. For feminism, 1989 meant a transition from a state socialist-Marxian universalism to the universalism of liberal democracies and of liberal human rights discourse. Moving away from the idea of general human emancipation that was at the core of the state socialist idea of a good society, the new liberal democracies imagined a just society as a community of (legally) equal citizens. This insistence on nominal equality, rather than difference, paradoxically made a lot of the feminist claims (often premised on a critique of systematic, unequal treatment), invisible, marginal or mainstreamed into insignificance, despite the efforts, wishes, and intentions of many feminist activists and intellectuals. The feminists of 1989 even deemed the concept of oppression difficult to use as the shadow of crypto-communism was hanging over the word and anyone who dared use it.

The political and discursive context didn’t leave much space for a coherent critique of global capitalism either. In post-89 eastern Europe, ‘global’ meant having a passport and access to the rest of the world, and capitalism could be just about anything as long as it was not state socialism. Apart from the former Yugoslavia, leftist philosophical languages enabling the critique of the freshly introduced capitalist system were practically absent in in the region. However, the anti-violence organisations always emphasized the role of economic violence against women as a constitutive part of the broader regime of violence, as well as the overall systemic patriarchal oppression of women. This started to change when a new feminist generation started to realize that the vocabulary of Marxian and, more generally, leftist social theories is essential to critically and constructively discuss the deep economic and social crisis brought along by post-1989 capitalism.

Gender mainstreaming and backlash

In the meantime, another, actually much more important process was underway. Civil organising was complemented, for better or worse, by EU directives and policies aiming at gender equality of what came to be called gender mainstreaming. For many countries, joining the EU or hoping for membership meant having to introduce such policies. While gender mainstreaming held the promise of finally bringing about many of the policies feminists in Eastern Europe had been demanding, it ended up undermining many of their efforts, and moreover, it triggered an anti-feminist backlash. The policies were rarely accompanied by substantial changes in public discourse or the political process. Local feminists did not become more visible, neither did demands and ideas not receive much more attention.

The shift from feminist movements to gender mainstreaming is far from an innocent one. The accent tends to be more on mainstreaming than on gender, though both concepts in themselves water down the demands of the feminist movement – and not just from the 1970s onwards but all the way from the 19th century. The eastern European feminist generation of 1989, while clearly marginalised by the intellectual and political elites, experienced a brief period of hope around the EU accession, and they used the legal harmonization in a desperate attempt to give more weight to their demands. Despite these hopes and the potential usefulness of European directives, the feminist generation of 1989 very soon had to realize that this kind of mainstreaming takes away from the innovative spirit of feminism. Talking about gender in a mainstream fashion instead of straightforwardly addressing feminism, women, power, oppression, exploitation and violence may make ideas of gender equality more palatable, but the rapidly emerging anti-gender movements on the misogynic and homophobic right are perfectly capable of identifying the original ideas tamed into gender mainstreaming. With the fading of the original vocabulary of feminism centred round the aforementioned concepts, we are now left with gender, a concept that is even easier to demonize.

This takes us back to the question of East and West. The anti-gender movements are a new, albeit not necessarily very original form of anti-feminism. Anti-gender ideas were reinvented in tandem with racist, anti-poor and anti-LGBT ideas in the 2010s, when east central European politics shifted toward authoritarian populism and large segments of European societies, in East and West alike, are becoming increasingly prone not only to tolerate, but to actually vote for extreme right parties. Anti-feminism is just as old, if not actually older than feminism, and anti-feminists in East and West have often maintained that feminism is alien to their country. The anti-feminism of fin-de-siècle England is not substantially different from that of late 19th century Hungary, the 1950s United States, or state socialist Yugoslavia of the 1970s. However, anti-feminism in the ‘East’ feeds into the idea of the Eastern parts of Europe being more savage and barbaric. We may indeed sense a certain voyeuristic pleasure in journalists’ reports, facebook posts, questions and comments at conferences about the anti-gender movements in Hungary and Poland – while even beyond the most obvious case of Trump, there is the forced liberation of women from being able to choose their clothes in France, or the constant attacks on women’s reproductive rights and their right to live a life without violence all over Europe and North America. In this sense, feminisms East and West share a lot and have as much to discuss as back around 1989.

Generational clashes, historical forgetting and the need for sisterhood

The new generation of feminists have brought a crucial turn in language and politics that has made feminist thought and activism stronger and much more ready to face the challenges of today’s capitalism in eastern Europe. Yet, their members often enter into generational clashes and at times even display matricidal tendencies. This phenomenon may be nothing new – American historian Christine Stansell has described the entire history of US feminism as a series of generational conflicts, and such an analysis would unfortunately prove useful in many other contexts too. Consciously neglecting or forgetting the ideas and achievements of earlier generations weakens the movement.

In the case of east central European feminism, post-1989 feminism is heavily criticized for its strong emphasis on the private and the personal, and its lack of focus on (global) economic inequality and class. But this critique overlooks the defining context. As Lepa Mlađenović, one of the feminist activists and intellectuals in the forefront of Yugoslav feminism since the 1980s, put it: ‘At the beginning, we had to work on ourselves first, to then be able to focus on others and work to end oppression of women that was maintained by male violence against women.’[2] Beyond that, the anti-violence activism of the 1990s, precisely because of its radical feminist roots, has been deeply vested in the scrutiny of the social and economic structures that make violence against women possible and even support it. Notwithstanding the aforementioned tendencies, many feminists of the younger generation constructively integrate the past knowledge into a new agenda and look ready to face current challenges.

Connecting the heritage of 1989 with the current situation as well as with its pre-history, the latest research of scholars such as Agnieszka Mrozik point to a different kind of generational forgetting: that of post-1989 feminists who completely forgot about their ‘foremothers’, especially those from the interwar activist women’s generation who became prominent communist politicians promoting women’s emancipation during state socialism. While Mrozik is correct about the need to research and reconstruct this past (and has also completed impressive work to do so), understanding the more immediate inheritance of feminists after 1989 requires studying the decades between the immediate post-WWII politics of state socialist women’s emancipation and 1989. The radical social transformation brought along by state socialist women’s emancipation politics in the Stalinist period was followed by waves of backlash throughout state socialism, from abortion bans to several measures pushing women out of the workplace as well as the political class – with few possibilities to speak up and organize. Eastern European women after 1989 remembered very little about the heroic achievements of their predecessors in the interwar and immediate post-WWII period while what they had to confront was a rigid patriarchal system using state socialist women’s emancipation as a justification of misogyny and anti-feminism.

The dynamics of forgetting and rewriting the past are tied to terminological misunderstandings, too. The unreflective use of the label ‘liberal feminism’ is often used for phenomena which have radical feminist roots and then get mainstreamed into post-feminism. Gender mainstreaming may be present in East and West, but is especially noticeable in recent scholarship about post-1989 feminism in east central Europe. However, early post-1989 feminism’s focus on violence, sexism and the representation of women was much rather a cavalcade of feminist ideas than parts of a straightforward liberal agenda.

The other phenomenon mistakenly assumed to belong to post-1989 liberal feminism is the ‘feminism’ on the pages of glossy magazines, which is in fact the post-feminist branding of empowerment, with its latest manifestation in the commercialized, absurdly sexualized version of the #metoo campaign. I would be hesitant to call this phenomenon the fault of any form of feminism; such expressions of post-feminism are simply yet another product of global capitalism.

Global capitalism pushes to conflate radical feminism with liberal feminism, and the forces a merger of both into post-feminism and gender mainstreaming, which constitutes shared challenges for feminists East and West of the former Iron Curtain. Women from the two sides of this historical divide have invested a lot into understanding themselves and each other better, into drafting agendas that would improve the lives of all women, and ideally help overthrow patriarchy.

Remembering the efforts of the 1989 generation and the achievements of the Yugoslav feminists of the 1970s, sympathetically looking back at these struggles and learning from the fruitful dialogues between East and West is crucial not only in order to avoid the erasure of the struggles of yet another feminist generation. The past thirty years help us not only by providing inspiration, they also teach us to be aware of seemingly attractive solutions, such as gender mainstreaming, which tame crucial feminist demands into empty solutions. There is a need shared by generations of feminists East and West to fight yet again to regain feminism for a political purpose, to go beyond the popularisation of feminism even, and especially in the face of extreme right wing nationalism and populism. This should not be that difficult if we were ready to embrace our history, because actually: feminism was never meant to be fun.