A muscle memory of misery

Yet another independent outlet is slain in Hungary: Klubrádió just lost its broadcast license, resuming a decade-long campaign to silence the channel. Journalists march on, hoping for a lengthy legal battle to do them justice in the end. They have accommodated pressure, but their defiance comes at a high price.

One benevolent lie popular with Hungarians is Palma sub pondere crescit, ‘the palm grows under weight’. It suggests something similar to ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’, another outrageously stupid statement – as anyone suffering lasting impairments, trauma and/or disabilities will confirm.

The proverb about palm trees was originally meant as a warning against overprotecting youth, but is generally used to rationalize debilitating pressure and unacceptable conditions. I’ve also heard people use it to cheer themselves up, in order to carry on under hopeless circumstances. In their case, I won’t complain, they’re working against the odds.Over the past years some of these people have been sustaining the independent Hungarian radio Klubrádió, whose broadcast license was withdrawn this week in an exceedingly technical court ruling. The decision resumes a decade-long campaign to silence the broadcaster: first its national frequency use was withdrawn, then its public service status was denied and its advertisers started to disappear. The station is continuing its legal battles and still broadcasting online.

Adapted from a photo by Timothy Abraham on Unsplash.

Klubrádió has been maintained mainly by listeners’ donations since 2012, well before the current subscription craze in online media began. It built a strong community at a time when other mainstream journalists mocked crowdfunding as begging. In the meantime, most of what remains of independent media in Hungary asks for donations, often on top of their subscription fees.

After the iconic Kossuth Rádió was transformed into a government mouthpiece as early as 2010, Klubrádió increasingly took over the position of the classical talk radio station, signing many former public service prime-timers. It became the substitute for the state radio that generations had grown up with since the first quarter of the twentieth century.

Klubrádió is not above criticism. Having worked there for four years, I’m not in the position to acquit them of charges of partiality. The outlet is traditionally left-leaning and has sided with the opposition in Hungary since Vikor Orbán first got his supermajority in 2010. Some of their iconic anchors are more establishment than the dying Hungarian Socialist Party itself; others sided with activists to such an extent that they ended up as opposition candidates in the last municipality elections. All over the region, from Ukraine to Slovakia, media workers seem to have formed a new breed of politician, and Hungary is no exception. And among such colleagues, more than a handful have kept innovating, bringing radio closer to a younger audience or discussing classical music as pop culture.

But an obvious political leaning, however disagreeable to those in power, is not the same as disrespect for democratic and professional norms, which Klubrádió has always observed. If anything, its struggle for survival has made the organization more open and straightforward. Its listeners, many of them elderly, are extremely mobilized and ready to support a variety of causes. In 2016, when the government tried to sweeten elderly voters before Christmas with a one-off voucher for 10 thousand forints (around €30, a considerable sum for many pensioners), Klubrádió called on its listeners to donate the money to an education charity. As a result the charity was able to cover not only its Christmas expenses but also an emergency food aid programme for the following year, helping out schoolchildren who couldn’t afford to eat.

Editor-in-chief Gábor Pataki is preparing for digital-only broadcasting until the legal procedure proves their case.

One can grow used to sustained pressure. The spirit, like the body, adjusts its growth to compensate for pain and restricted motion; certain muscles tighten when others are disabled. Under permanent pressure, this is what people do mentally too: they grow used to it and adapt their everyday lives to allow for what they actually can accomplish. One Hungarian writer has already gotten a literary Nobel for showing how one can make a home in suffering, so my ambition here is simply to revisit this concept.

In an interview with CityDog.by, Belarusian novelist Victor Martinovich describes a severe case of something similar. When two design students he had worked with were detained, they found solace in observing an orange peel dry. Its ‘colour gives them more life than anything in the world. They took the peels, laid them on a shelf and looked at them as if they were a Matisse or a Chagall.’

This ability is key to surviving and staying sane – whatever that means – in the face of severe adversity. But it comes at a very high price. It shrinks the person, robs them of their energy, their flexibility; it twists them into positions that they cannot straighten up from. It robs them of joy and life force.

For many, the sound of the radio is the signal that sequences time, filling voids, providing familiarity while introducing a sure dose of new into established habits. Those who are not tech-savvy enough for online listening – or who cannot afford internet access – are losing this connection to a world they knew and needed. They’re left stranded in a country with no free analogue medium beyond the illiberal government’s reach.

But these people cannot give up hope, since there are few other luxuries left for them. Pity alone doesn’t help – and neither has the European Commission. Although a spokesperson voiced ‘concern’ in a press briefing, former MEP Benedek Jávor reminds that a complaint about the treatment of Klubrádió was made two years ago and it still didn’t find the time to react to a sustained direct threat to yet another free medium in Hungary, where media are falling victim to political repression in bulk.

2yrs passed since we submitted complaint to @EU_Commission w #Klubrádió against unlawful state support to pro-gov't media & 5yrs since complaining illegal financing of public broadcaster. COM had no time to conclude, while HU gov't managed to kill the complainant #Klubrádió

— Benedek Jávor (@javorbenedek) February 9, 2021

Of course, a whole host of European institutions have long failed to enforce any measures against the ruling parties in Hungary, Poland and now Slovenia – to mention the most prominent offenders. Even when they use the corona crisis to increase their power and crack down on perceived foes – NGOs, newspapers, women who want to make choices, LGBTQIA+ people who want to be alive – the most we got were strongly worded reports.

Now that the polls indicate that Fidesz is facing an uphill battle in next year’s election (even in an electoral system categorized as ‘free but not fair’), the crackdowns on free media and opposition-led municipalities are getting more severe. Bleeding out Budapest is an obvious priority. The capital has been administratively stripped of a large portion of its income, and now EU developmental funds are being grabbed by Fidesz.

There is a bitter irony in watching a political power continue to be financed by its declared enemy.

Whether a united opposition can throw Orbán off the horse next year depends on a whole lot of factors. First, the opposition is not quite so united as it needs to be. The groundwork necessary to keep such a massive voter base involved and motivated has not been done. Since the centralized media landscape is sealed against anything apart from the party line, possibilities for reachout to anything non-aligned with Fidesz are extremely limited.

But even if by some political miracle the illiberal regime is toppled, a new government would face the accumulated pain of a society paralysed more than a decade’s worth of assault. How can the muscle memory of such misery be unlearnt? Who can we teach a whole society to hold its head up high and build decent leadership?

It’s not a rhetorical question.

This editorial is part of our 3/2021 newsletter. Subscribe to get the weekly updates about our latest publications and reviews of our partner journals.

Published 10 February 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

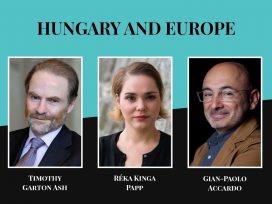

Prefiguring Europe’s future

Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia

Since the war in Ukraine, the Visegrád Four group no longer articulates a common voice in the EU. Even the illiberal alliance between Hungary and Poland has come to an end. Yet in various ways, the region still demonstrates to Europe the consequences of the loss of the political centre.

Pronatalism has become a populist vote winner for right-wing parties in Central and East European countries. Demographic imbalances, involving youth migration, ageing populations and immigration resistance, have sparked a series of baby-making policies. But are financial incentives in Hungary, Poland and Serbia enough to reverse the trend of decreasing birth rates?