'It’s important to be open'

A Knowledgeable Youth podcast

Remaining in a new country or returning home? The Knowledgeable Youth podcast delves into the complex decision-making refugees face when migrating, together with researcher Olena Yermakova.

Beware interpreting Ukraine’s current political landscape with traditional European values, says Volodymyr Yermolenko: Kremlin-backed zoopolitics, upholding the survival of the fittest, uses liberal discourse against the democratic world.

When Volodymyr Zelenskyy won the 2019 presidential election in Ukraine, Ukrainian philosopher Vakhtang Kebuladze called his phenomenon a ‘non-Maidan’. I repeated this expression in my interview for New Eastern Europe published in May this year. Kebuladze meant that Zelenskyy’s election undermined the 2013-2014 confrontation between the pro-European ‘Maidan’ and the pro-Russian ‘anti-Maidan’, and his political project – Servant of the People – intuitively or consciously sought a different approach: more inclusive but also more vague, a comprehensive platform attracting voters with different origins and values.

At that time, I called the Zelenskyy phenomenon ’populism 2.0’. During the election campaign, Zelenskyy was not proposing ideas, values or even slogans. He was proposing himself, his (real or imagined) character. The major emotion behind this character was the emotion of belonging: ‘I am one of you’, he tried to say, ‘I am not a politician, not a part of “them”’. Contrary to other politicians, he moved from political slogans (‘vote for us and we will give you justice/peace/security/welfare/order’) to political memes: his word play mocked current politicians or corrupt civil servants but did not propose anything like a plan or goal; he mobilized his voters to laugh at and reject other positions but gave no alternative.

This emptiness was Zelenskyy’s key drawback – but also his key force. The ideology of the Servant of the People was unclear but sufficiently comprehensive to attract different people and different expectations. This inclusiveness gradually made Servant of the People a key centrist force in the Ukrainian political landscape. It also helped crystalize two oppositions to the Zelenskyy party: the patriotic pro-western opposition embodied by Poroshenko’s European Solidarity and the pro-Russian, anti-western opposition embodied by Viktor Medvedchuk’s Opposition Platform for Life (OPSZ). Two lesser political forces are also worth mentioning here: the liberal (and probably most pro-western) Holos, led by rock singer Sviatoslav Vakarchuk; and the aggressively anti-western party of video blogger Shariy (the Shariy Party). While Holos is gradually dying out, ‘squeezed’ between centre-right Poroshenko and centrist Zelenskyy, Shariy is gaining popularity, especially among younger audiences in the east and south, by acting as a youthful and anti-systemic ally of the Opposition Platform for Life.

Another important Ukrainian political player Yulia Tymoshenko, one of the leaders of the Orange Revolution (2004-2005), is drifting more towards Ihor Kolomoiskyy and increasingly playing an anti-western card, pushed by the oligarch and his entourage. Add to this a bunch of local parties born of decentralization reform and some new oligarchic political projects, and you will see the usual, complicated character of Ukrainian politics.

This article was first published by Eurozine’s Polish partner journal ‘New Eastern Europe’. Read our review of their 6/2020 issue here.

It is very tempting to present this constellation in a European-style ideological matrix: centre-right European Solidarity (somewhat similar to the German Christian Democrats); the ‘centrist’ Servant of the People; the liberal Holos; the centre-left Tymoshenko party; the pro-Russian ‘left’ of OPSZ; the radical far-right Ukrainian nationalists (balancing between two and three per cent); and the “far-left” Shariy. However, all of these familiar adjectives – ‘right’, ‘left’, ‘centrist’, ‘liberal’, ‘nationalist’, ‘socialist’ – are hardly applicable as such to Ukrainian politics that is driven by personalities and money rather than ideas or ideologies. And, while on the pro-western flank there are at least signs of demarcation between more liberal forces and more patriotic/identity politics, the pro-Russian side is still characterized by a chaotic mixture of ideas.

Firstly, therefore, when I use the adjective ‘left’ with regard to Medvedchuk and Shariy, I use it as a metaphor rather than an exact description. They are trying to attract the attention of the European ‘left’, arguing that they are the key force opposing Ukrainian ‘nationalists’. But their ‘leftism’ is illusory and has nothing to do with a genuine European left; it is not about a welfare state or social redistribution but pro-Soviet nostalgia and pro-Russian rhetoric, acute anti-western rhetoric and weak claims that they oppose ‘nationalists’. They are also, quite probably, receiving financial support from the Kremlin; Medvedchuk and Shariy often display nostalgia towards the Soviet industrial, authoritarian and imperial past.

Secondly, Zelenskyy’s ‘centrism’ is rather wishful thinking. Its ‘inclusiveness’ is often a synonym of its emptiness that was rather vacuous at the beginning and is becoming increasingly bereft in the making: the 2020 local elections were poor even in terms of political campaigning when compared with the 2019 election.

Thirdly, there is no balance in this system. Currently, the ‘patriotic’ and ‘pro-western’ flanks (Poroshenko, Holos and pro-western MPs of the Servant of the People) are losing popularity and resources as targets of a huge anti-western information campaign, thoroughly studied by UkraineWorld.org. Meanwhile, the ‘anti-western’ flank (Medvedchuk, Shariy, Kolomoyskyy’s close politicians from Servant of the People and new parties like For the Future linked with Kolomoyskyy) are gaining popularity, primarily because of the huge financial and media resources behind them.

What does this trend mean for Ukrainian values? Nothing positive, that is for certain.

The liberal-patriotic alliance was key to the emergence of modern Ukraine. It was a significant factor in the Ukrainian dissident movement in the Soviet Union of the 1970-80s, which tried to combine the liberal discourse of human rights and the patriotic values of community rights and identity. The Ukrainian Helsinki Group, which emerged in 1976 in protest against the Soviet Union’s neglect of the Helsinki Final Act (the USSR eventually signed it), was a symptom of this. The opposition to Soviet totalitarianism, which suppressed both individual rights and the national/political identities of its ‘republics’, demanded a unified front of liberals and patriots.

Throughout the 1990s, this liberal-patriotic alliance dominated intellectual discourse. However, it had little understanding and support from the general public. The majority of Ukrainian society in the early 1990s was made up of the post-Soviet elite and ordinary citizens who had not taken this competition of ideas seriously and were focusing on material concerns. Some earned a lot of money from corrupt rent-seeking schemes or other successful businesses, while others were focused on economic survival and ensuring the basic daily welfare of themselves and their families.

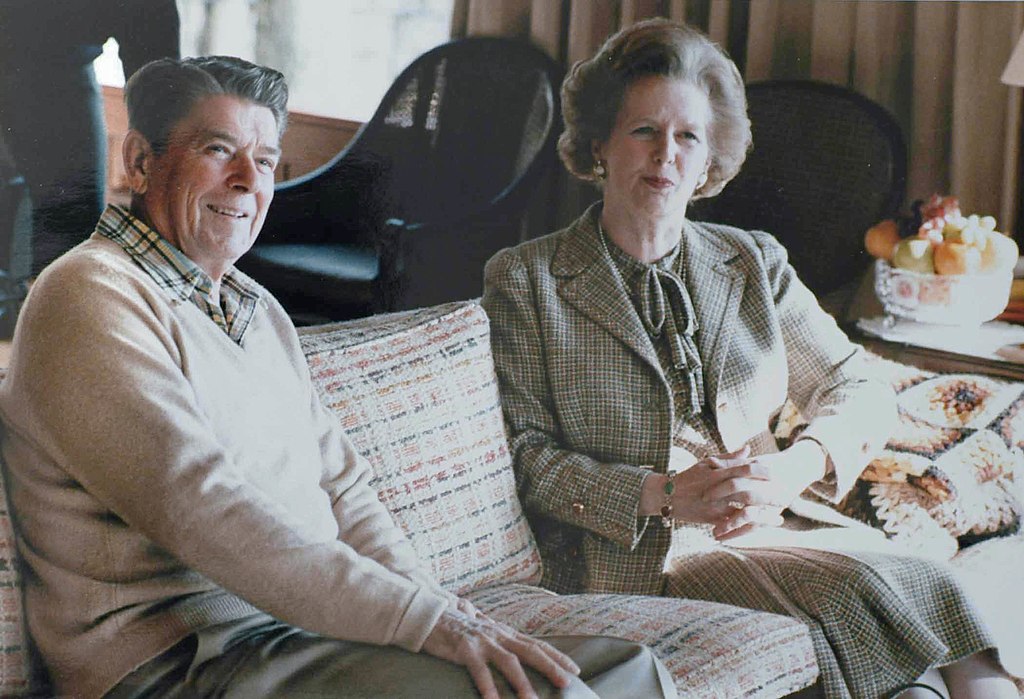

During the two Maidans (the Orange Revolution of 2004-2005 and the Revolution of Dignity of 2013-2014), this liberal-patriotic discourse, which stressed the importance of both human rights and the rights of the Ukrainian political community (against Russian expansionism, for example), was able to mobilize citizens and provide them with ideas that inspired resistance and even a readiness to sacrifice themselves. What is more, this liberal-patriotic alliance was not unique to Ukraine. It was dominant throughout the western world, from the late 1970s – with Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan – through to the late 1990s with a liberal-conservative consensus. This consensus replaced the liberal-socialist alliance of the 1940-60s, which created a European social model and welfare state that balanced the values of freedom and equality. Contrary to the liberal-socialist consensus, the liberal-conservative alliance of the 1980-90s rejected the role of equality as a key value and stressed the role of the rule of law, in addition to the liberal idea of freedom.

Reagan and Thatcher. Photo by White House Photographic Office, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Today, this liberal-conservative alliance has collapsed throughout the world. Former allies are turning into bitter enemies. Both liberalism and conservatism are becoming increasingly radical and intransigent in relation to one another. Ukraine, in this sense, is no exception. Several trends put the former liberal-patriotic alliance into question. ‘Liberals’ and ‘patriots’ are increasingly in opposition to one another. Russian aggression in Crimea and the Donbas have made patriotic discourse more radical, with many of its representatives doubting that the liberal values of human rights can be applied to the enemy, in a country at war. ‘Liberals’, on the contrary, argue that radicalizing patriotic, security and identity discourse is beneficial to Russia which presents Ukraine as a ‘fascist state’ and is turning Ukraine into a mirror of its enemy. The collapse of the liberal-patriotic consensus endangers the very resilience of the Ukrainian political project, facing increasing threats from Russia, not only from the outside but also from within the country.

The clash between liberalism and patriotism/conservatism mirrors a fundamental axiological clash, which we see around the world, including Ukraine: a controversy between the ‘warrior ethos’ and the ‘bourgeois ethos’. By the warrior ethos, I understand a set of values upholding the ideals of victory on a battlefield: glory, honour and pride. By the bourgeois ethos, I understand values upholding the ideals of exchange, mutual respect and a positive sum game.

The warrior ethos has been a long-lasting foundation of European ethical doctrines. It was the ethical basis of European Antiquity, primarily Ancient Greek city states, and is the foundation of Western democracy. It is based upon the idea that a true ‘virtue’ is won on the battlefield, on an agon. The ideal citizen is supposed to be able to fight, win and earn glory. The warrior ethos stresses the values of fighting for national sovereignty and identity, of sacrifice, heroism and victory in war.

The bourgeois ethos, on the contrary, emerged with European modernity, the rise of capitalism and the subsequent invention of political liberalism. It can be attributed to philosophers like John Locke, David Hume and broadly seventeenth to eighteenth century Britain. Contrary to the values of sacrifice, victory and glory, it emphasises mutual exchange and recognition. It stresses the values of a positive sum game and compromise. It presents the best metaphor to describe human society as agora, not agon – in other words, the meeting point, the market.

In my recent essay Ukraine, Europe and dignity, I argue that the combination of the warrior ethos and bourgeois ethos is key for the development of the idea of dignity (dignitas). Dignitas is important for both European Union values (‘dignity’ comes first in the list of values of Article 2 of the Treaty on the European Union) and for Ukraine’s recent history, whose EuroMaidan was called the Revolution of Dignity from its very beginning.

A united Europe was the result of an alliance of these two sets of values: a Europe of glory and a Europe of exchange; a Europe of victory and a Europe of compromise. Both needed each other. Dignitas is unthinkable without mutual respect and equality, which comes from the bourgeois ethos; however, it is also unthinkable when everything is subject to exchange and there are no red lines for compromise. These red lines come primarily from the warrior ethos and its emphasis on the value of honour.

Both have played a significant role in Ukraine’s recent history. The bourgeois ethos helped many citizens overcome their Soviet past, to become more individualistic and less dependent on the state, and better value horizontal relations, mutuality and trust. But the warrior ethos has also been key for Ukraine’s defence against foreign aggression. The value of sacrifice was acutely present both during EuroMaidan and the war. It is remarkable how the word ‘warrior’, voin, has renewed importance in the Ukrainian language.

The warrior ethos is the reason why many Ukrainians are sceptical of Europe’s policy towards Russia, which is considered by many as too soft, compromised and unwilling to confront danger (i.e., too bourgeois). Today, however, these two sets of values are also contested within societies one of the lines of conflict between liberalism and patriotism. Moreover, both are also facing attack from a third player – the Kremlin. Putinist Russia is perfect at imitating European values but altering them for its benefit – it skilfully plays on the controversy between liberalism and conservatism, either helping radical conservatives or imitating liberal discourse on ‘freedom of speech’ when it needs to.

In Ukraine, the Kremlin is also promoting what I call a ‘zoopolitical ethos’. By zoopolitics, I understand a specific worldview, in which politics – or the political as such – is understood not as a warriors agon or as the merchants’ market but as a big jungle where animals fight for survival. Zoopolitics valorizes aggression, force, expansion (i.e., the values of social Darwinism, which flourished in the western world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and led to the age of right and left-wing totalitarianisms of the twentieth century). Social Darwinism argues that human beings are neither warriors on the battleground, valuing their honour, nor are they merchants meeting at the market, valuing their mutual revenues. Instead, they are but animals fighting for survival, with no mercy towards each other. According to the zoopoolitical ethos, political competition is one big fight among big animals (nations, states, empires) trying to acquire more living space.

The zoopolitical discourse, typical for today’s Russia, has also been exported to Ukraine and other European countries, promoting the triumph of the cynical mind, which assesses the situation only on the basis of survival instincts and an aggressive capacity to destroy others. When I refer to zoopolitical (or social Darwinist) discourse in Ukraine, I mean primarily the abovementioned pro-Russian and anti-western forces – represented by Medvedchuk’s OPSZ, Shariy’s party and Kolomoyskyy-aligned political actors, both within the Servant of the People and outside it. They are characterised by an excessive use of hate speech, political incorrectness, and a rejection of both liberal (human rights) and identity (community rights) discourse. Openly or latently, they express their support for Russkiy Mir (the so-called Russian World) – a Russian imperial idea attempting to re-establish its zone of influence and, furthermore, to re-establish its political empire.

Interestingly, the zoopolitical ethos mimics both the bourgeois ethos and the warrior ethos. It uses liberal discourse against the democratic world. It argues that the western world promotes ‘liberal fundamentalism’ and that the Russian-backed discourse – on Ukraine media such as RT, Sputnik and Medvedchuk’s channels – actually provide the true alternative, genuine critical thinking and, therefore, should be defended according to the democratic principle of free speech. The truth, however, is that the zoopolitical goal is to use information as a harmful rather than instructive tool – to extend imperial power, not human knowledge.

It also mimics the warrior ethos, as it argues that Russkiy mir is endangered, encircled by its enemies that Russian people must fight, opposing any western attempt to weaken it. The truth, however, is that the European warrior ethos, rooted in the Greek polis, was citizen-focused, not empire-focused. It was initially much more anti-imperial than imperial. It was born much more as an ethos of the defender rather than that of the occupier – and, therefore, is much more applicable to the current anti-imperial Ukraine than to imperial Russia.

The Ukrainian liberal-patriotic alliance has been the key driver of Ukraine’s way towards European values of dignity. And, although it is not in the best of shape, it certainly could be reborn again. The problem is whether we can still find a universalist vocabulary to describe what is going on in today’s world or even what is going on among our neighbours. Take the Belarus protests, for example. Belarus’s uprising against Alyaksandr Lukashenka and Ukraine’s EuroMaidan in 2013-2014 have much in common. The true mobilizing force behind both was a response to direct police violence. It was this moment that provided the moral motivation to protest against violence and the civic motivation to protect citizens’ votes from fraud or the country’s geopolitical direction.

Yet, many place importance on stressing the differences rather than similarities between the Belarus and Ukraine protests. Some note Belarus’s lack of identity politics (for better or for worse). Others perceive the Belarus protests as less violent (the beginning the EuroMaidan was also non-violent). There are also those who complain that Belarus’s opposition is too soft on Russia. Although all of these differences seem to be less important than the aspects that unite the two protests, we still find it difficult to find a common narrative.

Unfortunately, the lack of a common narrative that goes beyond any particular state makes the very discourse of values senseless. Contrary to postmodern scepticism about grand narratives, I believe that our inability to embrace them makes us weaker, not stronger. The split between liberal and conservative values in the world, the split between liberal and patriotic values in Ukraine – or in other countries – and the radicalization of opposing discourses drives us away from the idea of ‘European values’.

‘European values’, with their focus on dignity, is a compromise between what I call the warrior ethos and the bourgeois ethos. And it is increasingly falling victim to the neo-authoritarian zoopolitical ethos, intransigent in its wish to survive. This zoopolitical ethos has only one motivation: destruction as a tool of survival. As one famous French writer put it, ‘destroy, she says’.

Published 21 December 2020

Original in English

First published by New Eastern Europe

Contributed by New Eastern Europe © Volodymyr Yermolenko / New Eastern Europe / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Remaining in a new country or returning home? The Knowledgeable Youth podcast delves into the complex decision-making refugees face when migrating, together with researcher Olena Yermakova.

The difference between knowing from distance that war is being waged and living that reality couldn’t be more extreme. But can awareness of multiple repercussions turn protective disassociation from violence into active solidarity? ‘The Most Documented War’ symposium in Lviv, Ukraine, provides valuable pointers regarding engagement and responsibility.