Just before midnight on 8 December 1986, in the hospital of a watch factory in the town of Chistopol in the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, Anatoly Marchenko, a Soviet prisoner of conscience, died at the age of 48. He had been transferred to the hospital from prison after his health had deteriorated dramatically following a hunger strike that he had declared in August and continued for several months. In a letter published twelve years after his death, he wrote that “Since August 4th I have been on a hunger strike, demanding a stop to the torture of political prisoners in the Soviet Union and their release.” He was buried unnamed with the number 646.

Five days after Marchenko’s death, Mikhail Gorbachev, the Secretary General of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, ended the political exile of Andrei Sakharov; soon after, all Soviet political prisoners were released. The end of the history of political imprisonment in the Soviet Union was followed by the end of the state itself. Marchenko’s death heralded an era of freedom on the territory of the former Soviet Union.

Strange and tragic

That freedom was very short-lived, however. The regimes of the former Soviet republics, now independent states, soon reverted to the repressive practices of the past. Over the years, these practices were perfected, becoming effective tools for autocratic and dictatorial regimes to maintain their power indefinitely.

In Belarus, events were developing in a strange and tragic way. Initially, of all the former Soviet republics, Belarus was the only one with a parliamentary system. Moreover, it was at the forefront of efforts to establish internationally recognised democracies in the region. It was the first post-Soviet state to apply for membership in the Council of Europe; today, it is the only European state that is not a member of the Council. Belarus was also one of the first former Soviet states to recognise and adopt the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Political and Civil Rights. This had been a taboo in the Soviet Union, since it empowered individuals to defend human rights against their own state. During this short period of liberalisation and recognition of international standards on human rights protection, Belarus made a huge contribution to international security in both nuclear and conventional terms. It is yet further proof that only a democratic country can be a real contributor to security, regardless of whether it is based on hard or soft power. The dangers posed by power-hungry Alyaksandr Lukashenka, who became the first president of Belarus, were underestimated both inside the country and internationally. Lukashenka ushered in a new era of ruthless, greedy, internationally irresponsible and unpredictable rulers in the three founding members of the Commonwealth of Independent States, a divorce mechanism established to avoid bloodshed on the territory of the former Soviet Union. The leaders of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine responsible for dissolving the totalitarian state – Stanislav Shushkevich, Boris Yeltsin and Leonid Kravchuk respectively – were long gone from power and their successors were busy reversing the process of democratisation in the former Soviet republics. Ukraine has since made a second and more serious attempt to break away from the past and put a stop to the authoritarian tendencies in its politics. It is now trying to build a democratic and independent future.

The dangers posed by power-hungry Alyaksandr Lukashenka, who became the first president of Belarus, were underestimated both inside the country and internationally. Lukashenka ushered in a new era of ruthless, greedy, internationally irresponsible and unpredictable rulers in the three founding members of the Commonwealth of Independent States, a divorce mechanism established to avoid bloodshed on the territory of the former Soviet Union. The leaders of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine responsible for dissolving the totalitarian state – Stanislav Shushkevich, Boris Yeltsin and Leonid Kravchuk respectively – were long gone from power and their successors were busy reversing the process of democratisation in the former Soviet republics. Ukraine has since made a second and more serious attempt to break away from the past and put a stop to the authoritarian tendencies in its politics. It is now trying to build a democratic and independent future.

In Belarus, Lukashenka has managed to build the model of a dictatorial state that is eagerly and effectively exploited by Vladimir Putin. The same model is also used in other former Soviet states, and was brought to its logical, aggressive completion by the Kremlin, which has started war in Europe against Ukraine. The uncertainty of the 1990s transformed into the consolidation of autocratic and dictatorial regimes and created a ‘cooperative of dictators’ in a majority of the former Soviet republics. Their leaders may be at odds on economic, social, trade and even political matters, but they always agree and support each other’s contempt for human rights and basic freedoms.

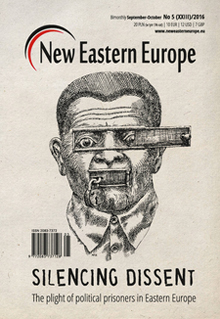

The primary shared attribute of all these regimes is political prisoners, people thrown in jail for holding political beliefs that do not coincide with the views of the ruling group, people who are not afraid to speak up and act publicly against the regimes in their countries. It is indicative that no serious human rights violations were known to have occurred in Belarus in the first few years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. It all started when Lukashenka came to power; since then, the situation has only been getting worse.

Vulnerabilities

One thing should be remembered about political prisoners and political repression in general: they illustrate both the nature and the vulnerabilities of a regime. Repression is directed at the parties a regime considers to be its greatest threat. This can even take the form of political assassination, as was the case in Belarus in 1999, when several opposition leaders, notably Viktar Hanchar and Yuri Zaharenka, were abducted and never seen again. In Russia, several opposition politicians have been murdered, most recently Boris Nemtsov.

Nevertheless, despite all their demonstrative strength, dictatorial regimes are vulnerable. Firstly, they are not protected by international law. This is the most important factor in both the domestic and the international fight for freedom and against tyranny. Although dictators seem happy to demonstrate their contempt for the international community, especially when it voices concerns or demands respect for human rights, they in fact keep a close watch on the international reaction to abuses, and respond with harsher repressions when the reaction is weak.

One phenomenon is particularly striking. Over the last ten to fifteen years, there has been a visible increase in the number of human rights organisations, at both the domestic and international levels. At the same time, there has been an increase in both the number and severity of human rights violations. This is not because of the failure of human right defenders, the majority of whom are committed, courageous and honest. Rather, the fault lies with the failure of intergovernmental organisations to uphold human rights standards. In Europe, where Belarus belongs, the relevant organisations include the Council of Europe, the European Union, and the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe. Their inaction directly affects the human rights situation in countries like Belarus.

There is an increasing tendency towards realpolitik regarding human rights. This tendency became stronger after the invasion of Ukraine by Russia and pro-Russian forces. European and international organisations founded on democratic principles have begun weakening those foundations by taking soft positions on human rights abuses, referring to ‘changed geopolitical circumstances’. They increasingly yield to the pressure of dictatorial regimes and their supporters. Geopolitical, economic and business arguments have begun to prevail where policy towards dictatorial regimes such as Belarus is formed. Human rights have fallen victim to the politics of ‘new pragmatism’.

There is also a tendency among European institutions to collaborate with or even create think-tanks that are closely linked to the regimes, and to base assessments of the situation on their loyal analyses. It has to be stressed that such policies have never been successful and that, more often than not, they lead to harsher repressions, provoke disturbances inside a dictatorship, and destabilise the situation in a region. In this age of multiple European and global crises, the need to uphold values has become pressing. Values matter. Emphasising them helps solve geopolitical problems, not vice versa.

International support

It is important to remember that the fate of political prisoners directly and proportionally depends on international attention, solidarity and action. Of course, the key element is domestic solidarity and attention, which in turn leads to international campaigns. When we speak of political prisoners, we refer to non-democratic countries that have no separation of powers and no independent judicial system. In these cases, the international community can act as a democratic judiciary, highlighting human rights violations and demanding that they end. The absence of international pressure leads to more impunity for the perpetrators, whether individual officials or state institutions.

For political prisoners, it is extremely important to know that they are not forgotten and that their sacrifice is being recognised, both in their countries and around the world. I understand this very well from experience, when I was thrown behind bars for running against ‘Europe’s last dictator’ and was recognised by the international community as a political prisoner.

There are two kinds of approaches to being in prison. Some argue that in prison, there is life and even freedom: it depends on the person and his or her perception of reality. Others disagree.

I belong to the latter camp. For me, prison is existence without life. Moreover, I believe that it is dangerous to presume any normality in an abnormal situation where one is deprived of freedom. It is an ordeal that one has to go through in the fight for freedom and principles. One must try to survive. However, behind bars, it is crucial to have a strong connection with the outside world, because it is outside prison that life and freedom exist. That is why letters of support to political prisoners are so important. Receiving support from people who you do not know is as important as the backing and love of family and friends.

Political prisoners are jailed for their beliefs and principles. They fight for freedom, not just in their own countries, but for all of us. They care about freedom and justice, they care about us and that is why we must care about them. It is important to remember that we cannot create ‘first class’ and ‘second class’ prisoners. It is often the case that attention is focused on better known individuals, while those who are lesser known are ignored. Tyrannies understand this and apply their repressive practices accordingly. By harassing and jailing less visible activists, they achieve two goals simultaneously: to keep society under control and to avoid the strong international reaction that would inevitably ensue if more prominent activists were incarcerated.

This is what is happening in Belarus, where the regime, under the burden of international pressure, has released a number of well-known political prisoners to placate public opinion, while immediately beginning to jail other, less ‘famous’ individuals such as the human rights activist Mikhail Zhemchuzhny. European politicians eager to improve relations with Lukashenka prefer to ignore these facts, and consequently are easing pressure on the regime to change. This kind of ‘new pragmatism’ will only lead to new and harsher repressions.

Not long ago, in Łódź, I had the opportunity to listen to the famous Chinese dissident, author, musician and poet Liao Yiwu, who spent several years in a communist prison. He impressed me with one very simple thought: ‘The Berlin Wall would not have fallen were it not for the Tiananmen Square protests.’ In very simple terms, he said that the fight for freedom is universal and has to be supported by the democratic world, in every corner of the world.

Because of the strong reaction it provoked around the world, Anatoly Marchenko’s sacrifice led to the freedom of many. The attention and reaction of ordinary people – the media, human rights defenders and all those who care about any political prisoner – is of great importance, since it really does force politicians to act. That is the power of those who care. That power can make our world a better place.

The dangers posed by power-hungry Alyaksandr Lukashenka, who became the first president of Belarus, were underestimated both inside the country and internationally. Lukashenka ushered in a new era of ruthless, greedy, internationally irresponsible and unpredictable rulers in the three founding members of the Commonwealth of Independent States, a divorce mechanism established to avoid bloodshed on the territory of the former Soviet Union. The leaders of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine responsible for dissolving the totalitarian state – Stanislav Shushkevich, Boris Yeltsin and Leonid Kravchuk respectively – were long gone from power and their successors were busy reversing the process of democratisation in the former Soviet republics. Ukraine has since made a second and more serious attempt to break away from the past and put a stop to the authoritarian tendencies in its politics. It is now trying to build a democratic and independent future.

The dangers posed by power-hungry Alyaksandr Lukashenka, who became the first president of Belarus, were underestimated both inside the country and internationally. Lukashenka ushered in a new era of ruthless, greedy, internationally irresponsible and unpredictable rulers in the three founding members of the Commonwealth of Independent States, a divorce mechanism established to avoid bloodshed on the territory of the former Soviet Union. The leaders of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine responsible for dissolving the totalitarian state – Stanislav Shushkevich, Boris Yeltsin and Leonid Kravchuk respectively – were long gone from power and their successors were busy reversing the process of democratisation in the former Soviet republics. Ukraine has since made a second and more serious attempt to break away from the past and put a stop to the authoritarian tendencies in its politics. It is now trying to build a democratic and independent future.