‘Post-truth’ became the word of the year in 2016, after Brexit and the US election campaigns. And quite soon news emerged, both in the United States and the United Kingdom, about the massive scale of influence from Russia on these elections.

There have been some evidence surfacing. Some of them have even reached the level of officialty, for instance the Mueller inquiry in the United States. There is no doubt that Russia had attempted to interfere with these elections, and had done so not only by providing financial support, media input in form of hacks and leaks, and disinformation via media channels such as RT and Sputnik, but through an arsenal of fake social media accounts, bots and paid trolls as well.

By now it has become a commonplace that Vladimir Putin’s Russia is both capable and willing to tap into every European elections. Neither is entirely true. In some cases, Russia does not have to directly interfere, as it feels that the political direction is beneficial anyway – for example in the last Austrian and Hungarian parliamentary elections. In some other cases, they feel they do not have the allies and the tools – as in Norway, for instance. So, instead of generalizing statements about the Russian influence, we have to examine the cases one by one for a proper evaluation.

Suspecting Putin behind everything. Photo by Don Fontijn on Unsplash.

External or internal?

EU institutions have published a joint document after the EP election in a strongly self-congratulatory tone, which claims that while there were sporadic, non-centralized efforts from the side of the Kremlin to interfere with the elections, they weren’t really successful – because of the EU’s responses, of course. ‘Measures taken as part of the Joint Action Plan against Disinformation and the dedicated Elections Package contributed to deterring attacks and exposing disinformation’, while ‘increased public awareness made it harder for malicious actors to manipulate the public debate’, the document argues. It even mentions measures supporting media literacy among the reasons why disinformation wasn’t so successful this time. This statement is a bit strange, given that the policy document they refer to was passed less than a year ago, and education projects rarely have impact in this short timeframe.

The document comes up with some examples for Russian-supported disinformation as well: one of them was depicting the Notre Dame fire as a symbol of decline of western and Christian values in the EU and the inability of authorities to deal with it. The collapse of the Austrian government was also interpreted as the result of a ‘deep state conspiracy’ by some propagandistic outlets. ‘This confirms that the disinformation campaigns deployed by state and non-state actors pose a hybrid threat to the EU’, the document concludes.

The problem is that the document misses the main point and acts naive. This is of course institutional naivity: it presupposes that the member states themselves are all interested in pushing back the issue of disinformation, which would mainly come from external sources. But most disinformation is home-grown and spread by domestic political players (sometimes governmental parties) for domestic political gains.

For example, Hungary’s deputy prime minister, who belongs to the Christian Democrat Party, a Fidesz satellite, expressed his belief that the Notre Dame fire was not just the symbol but the consequence as well of the decadent, secular trend in the whole western world, including France. In another case, not just pro-Russian disinformation outlets, but also political allies of the Austrian FPÖ in Europe tried to spread the theory that Heinz-Christian Strache and the Austrian government was brought down by an international conspiracy led by George Soros. Do they do it following the order of Vladimir Putin? No, they do it for their own vested domestic political interests. Focusing mainly on external sources of disinformation while ignoring domestic ones reflects a kind of ‘head in the sand’ tactic on behalf of EU institutions.

A not-so-important election

And while, of course, there were attempts to interfere into the EP election, they did not really come close to what we could observe around the Brexit vote, the US presidential election, or the last French presidential elections. No plausible evidence has been surfaced for a mass-scale external influence on the last European elections, even though we could find disinformation spreading all around.

Putin has several good pragmatic and ideological allies in the European Parliament, both in the mainstream, like the German Social Democrats, and also more on the extreme, with figureheads like Salvini, Le Pen, Strache, or Die Linke and AFD. Putin’s Russia has so far financed fringe parties and politicians and has given them public boost and endorsement. In turn, they supported Russia’s interests via words and votes in the European Parliament.

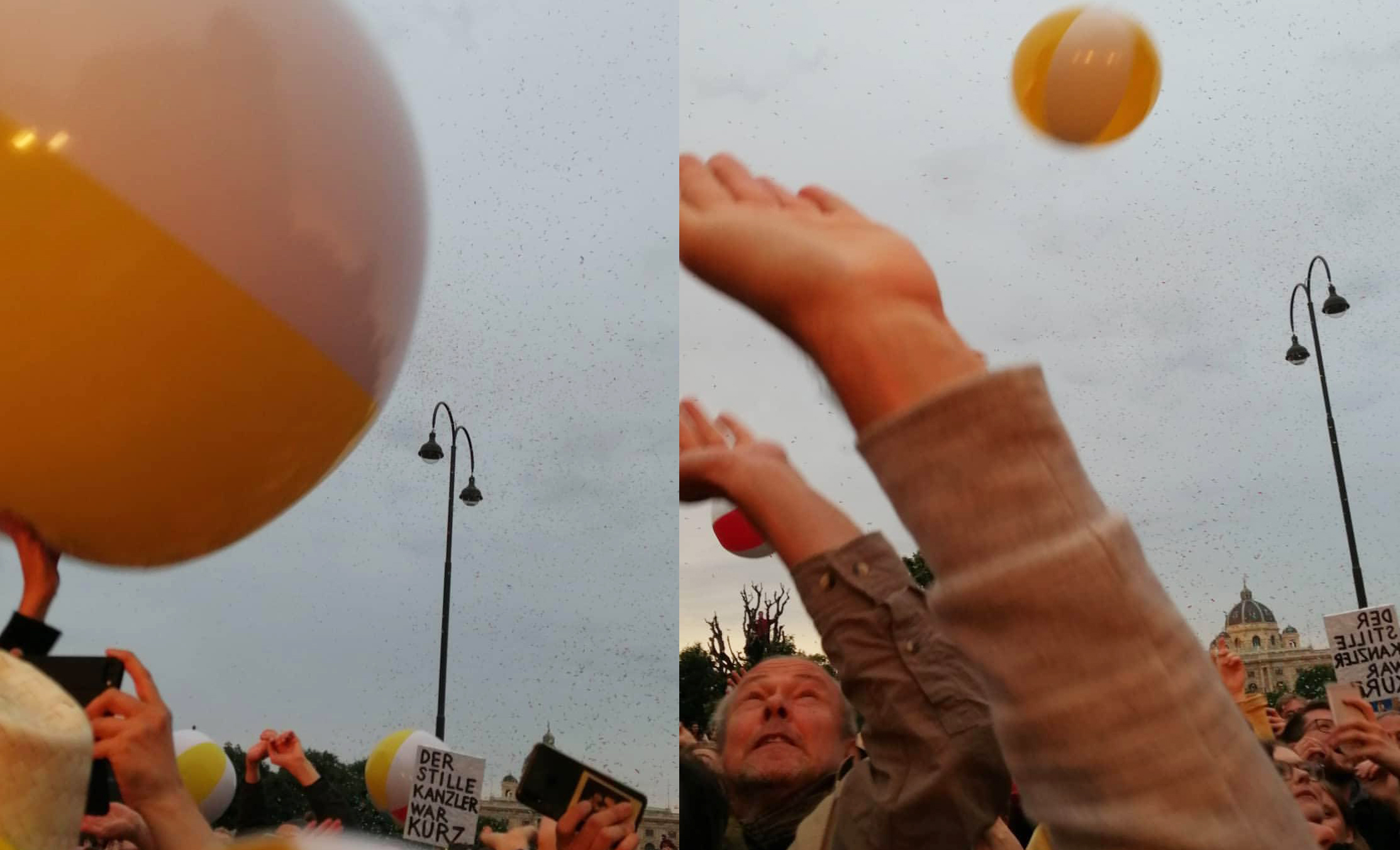

Audience plays games at Vengaboys concert in Vienna after the Strache scandal broke. Photo by Merve Akyel for Eurozine.

Still, we could not see a very strong push towards these forces. The optimistic reading: the Kremlin could not make a strong impact. The pessimistic one: they did not feel they had to.

Both can be true at the same time. On the one hand: changing the electoral outcome in the European Parliament would need an interference in several large EU member states, such as Italy, UK, Germany, France, Spain, Poland and more. Coordinating this massive scale of cyberattacks and disinformation campaigns would require such tremendous resources which Russia, despite popular belief, does not necessarily have. In some of these countries the Russian attempts to influence have proven unsuccessful. Take France, for instance: Emmanuel Macron was elected even though Moscow wanted him the least in the presidential seat, and they backed Fillon and then Le Pen instead.

The advantage of a possible interference was also questionable. In EP-elections we do not see the kind of direct impact between the outcome and the consequences as were traceable in the case of the election of Trump or the Brexit vote. It is likely that the European Parliament will not even manage to send a Spitzenkandidat to the EC presidency. And while the gravity and importance of the European Parliament is increasing, its relevance as a decision-making body is still lagging behind the European Council – so Russia puts more effort in elections in the member states than in the EU parliament.

Disinformation has played a role in the last EP election campaign though. As our research has proven, a massive wave of disinformation about the European Union has swept through multiple member states, most prominently the Visegrád countries, but also in Italy, Germany, and more.

Yet the main sources of disinformation were domestic political players, such as Viktor Orbán in Hungary and Matteo Salvini in Italy, who spread narratives about the EU with zero connection to reality. In these theories Brussels is in cooperation with billionaire philantropist George Soros to bring as many Middle Eastern and African migrants to Europe as possible, only to destroy the sovereignty of nation states. The pro-Russian media is sending similar messages about the European Union. Yet it is crucial to understand that Orbán, Le Pen, Salvini and their peers engage in these conspiracy theories about the European Union not because Vladimir Putin directs them to do so, but on their own terms, simply for domestic political gains. And, as their results suggest, with notable success.

As Political Capital concluded in a research paper: ‘While official, semi-official Kremlin-backed media can influence local pro-Russian actors’ messages, the views of local actors also contribute to the official pro-Kremlin rhetoric. All in all, European pro-Kremlin, Eurosceptic actors (most of whom are likely to be ‘useful idiots’ rather than Russian agents of influence) play a much more important role in spreading pro-Russian narratives in the EU than the Kremlin itself. Nevertheless, Moscow can be satisfied with this, as these narratives still reach the European audience and have an even larger effect through the former.’ It is a shared interest of Russia and European eurosceptics to spread misinformation aiming to destroy the image of the European Union. But the problem is more home-grown than external.

The problem is domestic

While Russian disinformation in Europe remains an important issue, the main driver of disinformation is not foreign intervention, but domestic politics. In an increasingly divided and polarized political environment, a tribal mindset emerges – defeating my opponent through any means, while putting my trust in the leader of my tribe. For being successful in tribal wars, one needs tribal myths: weaponized information against other perceived tribes. Disinformation often provides raw material for such myths, which are then used to justify transgressive political acts and mobilize likeminded tribalists against their perceived shared enemy. And members of these tribes are happy to believe in these myths as long as they prove successful. The fight against disinformation should target this essential component. As long as politicians are interested in spreading fake news for domestic political gains, the impact of policy responses relying on them will always be limited. If they receive information weapons from an external ally (from Russia or China, for example) to win their tribal political war, they will not be interested in pushing back. They will be happy to accept it.

It is a good development that the EU finally has an action plan against disinformation. Also, it is a breakthrough that it names Russia as one of the main source of disinformatin. The disinformation monitoring EAAS Stratcom Team does a very good job in tracking disinformation, and my institute, Political Capital is proud to contribute to that by reporting from Hungary. The tools the Action Plan proposes make sense. Fact-checking is important, and so is the education of critical thinking, source critique and institutionalization of the fight against disinformation in governmental structures. But it is not realistic to expect governments in Budapest and in Rome to push back against disinformation.

With politicians invested in exacerbating the problem, we cannot except that they will be the ones who solve it. Since some governments in the EU are more interested in spreading fake news than stopping it, the role of social media companies will be crucial in trying to prevent the massive scale of spreading disinformation.