Under Soviet rule, Ukrainian national consciousness remained dormant and independence an unspeakable taboo. When the desire for freedom erupted, it expanded far beyond the marked route of perestroika. On the 30th anniversary of Ukrainian sovereignty, Mykola Riabchuk recounts a personal history of how independence was conceived, formed and defended.

It seems I became a ‘nationalist’ long before I learned that ambiguous word, let alone the elusive concept it signified. In my teens, I was looking at the large political map of Europe in the classroom, where all the Soviet republics were painted in different colours, with distinct borders, names and national capitals.

It was during the break, with just a few boys staying in the classroom, when I raised the question. It was more musing than real inquiry. And yet, the boys responded vividly. They were as curious as myself: why a huge country of 50 million people, with a distinct language, culture, and history, couldn’t have the independence of Poland, Hungary, or Romania?

We were aware of political differences and the East-West divide, so we did not liken Ukraine to France or Italy. But how come we didn’t par with Bulgaria? Czechoslovakia? Or, well, Mongolia?

From our arguments the ultimate, truly consensual and profoundly philosophic conclusion arose: ‘If independence were possible, Ukraine would have already achieved it’.

This wise conclusion probably prevented us from asking the same question to our parents or, God forbid, our teachers. We certainly felt that the word ‘independence’ was somehow stinky when applied to the Soviet republics, especially to Ukraine. We were taught since kindergarten that Ukrainians and Russians are ‘brethren’, that the former cannot survive without the latter, and those who attempted to separate the Siamese twins were our (and humankind’s) worst enemies.

It wasn’t merely a political map that evoked subversive ideas in my boyish head. Daily life induced similar questions. Why were all the movies in theatres dubbed in Russian, while nobody seemed to care about Ukrainian? Why did almost all TV programs, with a few pathetic exceptions, air in Russian? Why would Russian speakers never switch to Ukrainian, but expect instead that one would switch to their language?

Dared you defy this unspoken rule, they may well have labelled you a ‘nationalist’, – a charge of criminal weight at the time.1 Remarkably, all kinds of ‘bourgeois nationalism’ existed within the Soviet Union – Ukrainian, Georgian, Latvian and so on, but no ‘Russian nationalism’; so much so that even this phrase was unfathomable.

Parents were of little help. My mother was an Easterner and a committed communist – a rare phenomenon at the time when party membership was primarily a career requirement. She maintained that the original Leninist policy may have been distorted by Stalin, but it would only be a matter of time until it was fixed.

My father, a Westerner and, like most locals, a cynical double-thinker, explained to me that might makes right, and some animals are always more equal than others. He acquainted me with the saying, ‘one cannot beat the butt with a whip’.2

The teachers were even less helpful. I still remember how perpetually scared one of them was – the brightest and seemingly the most decent. He hysterically demanded that we remove an innocent picture from the back wall of the class, a double-page from the Soviet magazine with the artistic photo of a yellow wheat-field under the blue sky. It wasn’t illegal, but the colours ‘accidentally’ resembled those of the Ukrainian national flag, or, in those times’ view, a ‘nationalistic’ flag: the official yellow-blue symbol of the short-lived (1918-1920) Ukrainian National Republic.

Yet another wheat field in good weather that accidentally resembles the Ukrainian flag. Image by Rudy and Peter Skitterians from Pixabay.

All those small instances added up in my head, and I’m reluctant to attribute to mere chance what happened afterwards. When a question haunts you, when you’re seeking an answer, you are likely to find something.

Before graduating from high school, older friends gave me a samvydav3 monograph, titled ‘Internationalism or Russification?’, by the prominent Ukrainian intellectual Ivan Dziuba. Based extensively on Lenin quotes, it largely confirmed my mother’s idea of a benevolent but distorted communism. However, the harsh reprisal against the author and the persecution of those who read and disseminated his work simultaneously confirmed my father’s wisdom.

I did my best to avoid the conflict of interests, diverting my anti-communist inclinations from the mandatory ideological brainwashing at the university, and opted for hard sciences instead of humanities, at the time supercharged with dogmatic Marxism-Leninism.

It was 1971, I was 18 years old. The political thaw was over, the country was entering another Ice Age, and the only freedom we could dream about was our internal freedom; the only independence we could covertly cherish was that of our informal, alternative intellectual life.

More open than intended

Ten years later, when senile Soviet leaders started dying one after another, getting ‘a season ticket to the funerals’ became a grim but popular joke at the time. We started to feel that something was going to change. We couldn’t predict the scope or direction of the eventual changes, but understood that the system was economically dysfunctional and increasingly uncompetitive, that the communist ideology had completely lost any mass appeal, and that the professed goal of ‘catching up with the West’ was just a bad joke under the circumstances of deep stagnation and total disillusionment.

Yet, on other hand, we knew that the system, however rigid, was deeply entrenched, and could well survive for decades with its multimillion members of the Communist party, mighty secret police, formidable nuclear arsenal, and strict control over information.

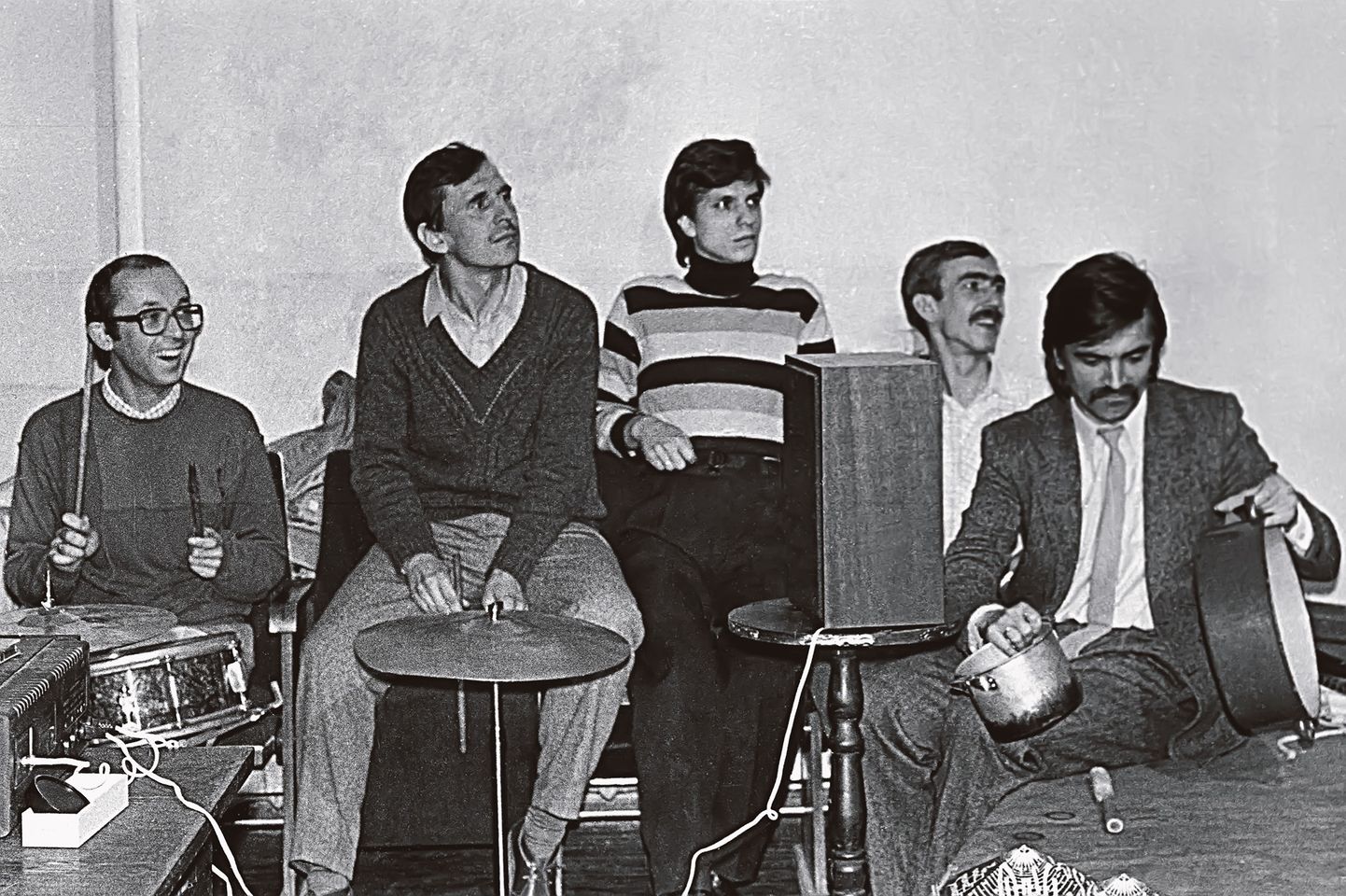

A group of young Ukrainian writers and artists in the famous Mykola Riabchuk’s ‘kitchen’ in Lviv where many counter-cultural events were held in the late 1970s. Photo from the author’s personal archive.

So, the horizon of our expectations was rather narrow. The best thing we could imagine for our country was a version of the 1968 ‘Prague Spring’, and possibly a (re)turn to its programme, ‘socialism with a human face’. We hoped for the end of Russification, non-interference into the cultural (apolitical) life, – a soft version of communism, like in Poland.

Poland was not only the closest neighbour, but also the main channel of alternative information about western art, literature, cinema, and modern music. We wished for the boundaries of the permissible to extend to what Polish intellectuals enjoyed and vigorously broadened.

The new Soviet leader elected in 1985 was a colourless apparatchik, distinguished only by his relatively young age from his gerontocratic colleagues and predecessors. His first words and steps were uninspiring: a mild criticism of some minor flaws and shortcomings was framed within the traditional rhetoric which identified Soviet communism as a good system that should become even better. Hence, his first programmatic slogans boiled down to ‘further improvement’ and ‘acceleration’.

Mikhail Gorbachev was the eighth and last leader of the Soviet Union. He became general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1985 at the age of 54. Photo by RIA Novosti archive, image #359290 / Yuryi Abramochkin / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons.

The talks on ‘glasnost’ and ‘perestroika’ (openness and reconstruction) arose in the following year, right after the Chernobyl disaster or, more precisely, after the shameful attempts to silence, downplay, and manipulate the news about a large-scale explosion at the major nuclear electric plant near Kyiv.

The media of the time gladly responded to Gorbachev’s call, and so did also informal civic organizations that rallied around the seemingly apolitical issues of ecology, cultural heritage, health care and the likes. Professionals of two distinct areas took the lead: culture and academia. Not that these areas and institutions were beyond the Communist Party’s control, far from it. But the very status of ‘creative workers’, bearers of a particular knowledge and skills, forced the Party to tolerate certain deviations in this milieu, relying more on carrots than sticks.

Crucially, those institutions had their own premises to host informal meetings, and their own outlets allowed for challenging publications. The local authorities were confused by the mixed signals from Moscow and often did not know how to react.

The ‘openness’ of glasnost was intended more to buy legitimacy than to enforce significant change. But in this political climate, the mere slogan rolled forward like a snowball, aiming apparently at a full freedom of speech. Every day new, previously banned topics were recovered, proscribed names revealed, and prohibited texts (re)published.

It was a dizzy, intoxicating time when the space of freedom expanded almost exponentially, and we almost felt its daily advancement physically. Yet we also felt that the process could at any moment be easily stopped, reversed, crashed, extinguished; there were no institutional mechanisms that could sustain it or guarantee its irreversibility.

One of the first literary performances held semi-officially, thanks to the Gorbachev policy of ‘perestroika’ and openness, at the Les Taniuk’s ‘Metrobud’ studio in Kyiv in the mid-80s. Photo from Mykola Riabchuk’s personal archive.

So we bought all the formerly banned books and subscribed to all the ‘progressive’ journals that had suddenly reached multimillion circulations. Several lives would have barely sufficed to read all of them but we voraciously accumulated those riches, predicating on the fear that the thaw would shortly end up, another Ice Age would set in, and we, proud holders of the rare, unique literature would again be secretly sharing it with friends and relatives, and handing them on to the next generations.

In 1985, I resumed my studies in Moscow, at the Gorky Literary Institute, after being expelled twice from university in the 1970s – for taking part in a literary ‘samvydav’ and, worse, holding inappropriate contacts with Ukrainian dissidents. There, I shifted from prose and poetry to literary criticism as I felt it provided much better tools to influence public debate. I was eventually invited to head the criticism section at the reputable Kyiv-based journal Vsesvit (The World).

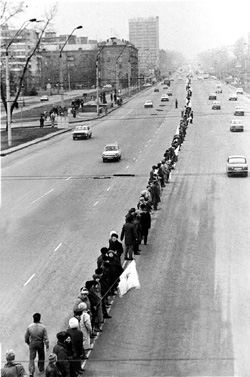

In January 1990, we organized the first large-scale political demonstration in Ukraine: the live ‘chain of unity’ between Kyiv and Lviv was apparently modelled on the 1989 ‘Baltic chain’ that commemorated the ill-fated Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement. Our ‘chain’ celebrated the 1919 Act of Unification between the two short-lived Ukrainian republics that emerged from the ruins of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires.

Act Zluky. Photo by Ostap R via Wikimedia Commons.

Eight months later, the disgruntled students of Kyiv launched a hunger strike at the central square, demanding the dismissal of the government that had arguably sabotaged perestroika. They demanded that new, multi-party elections be held.

The strike turned into a protracted stand-off as the authorities neither dared to disperse the protesters by force, nor to meet any of their demands. It was the time when the central square named officially after the October (Bolshevik) Revolution acquired its current name, Independence Square. It occurred spontaneously, coined by the bottom-up initiative of the Kyiv denizens who began to apply the new name as proof of their solidarity with the students.

A group of young Ukrainian writers had come to support the students at the political hunger strike in Kyiv, in September 1990, at the Square of the October Revolution (now Independence Square, a.k.a. Maidan). From Mykola Riabchuk’s personal archive.

One day, the rumour was spread that the authorities planned to terminate the protest with the help of the football fans. The idea looked rather simple: the Olympic stadium was located a mile away from the Square, and the football fans had an old tradition to march on the city centre after matches, along the main avenue called Khreshchatyk. They would march in orderly rows, chanting militant slogans and singing songs.

The devilish plan might have worked, had the provocateurs managed to set the fans against the students. The protesters couldn’t have withstood a huge, overexcited crowd. We, a host of intellectuals, fully understood this but decided to go to the square that evening, not so much to protect the students physically – it would have been absolutely utopian – but, rather, with a slim hope that the presence of public figures and journalists in the square would discourage the organizers from provocation.

I remember sitting on the cold granite of the square, next to the students’ tents, smoking nervously and listening to the powerful roar of the thousands of fans as they neared us, giving rhythm to their steps like at the military parade. The tension climaxed as they approached the square bypassing the tent-camp along Khreshchatyk street.

And suddenly, in a brief moment of silence in-between the chants, some choreographer in the crowd bowled out the popular slogan of the Ukrainian revolution: ‘Ukraini – voliu!’ (Freedom to Ukraine!). Thousands of football fans, hardly ever engaged in politics, picked up the slogan and happily passed the square with those two simple words, as we gazed at them in astonishment.

It was the first time that I felt that sooner or later, Ukraine would inevitably gain independence. And so it happened, in only a year.

What won’t fill your belly

In August 1991, as the Soviet Union collapsed and all the ‘union republics’ rushed away like smaller matrioshkas escaping from the biggest one, Ukraine appeared to be the only republic that decided to approve and fully legitimize the decision of the parliament at the national referendum.

For many, the initiative looked rather risky since Ukrainians had already held a similar referendum in March that year, and its results did not bode well for the national cause. Back in March, more than two thirds of Ukrainians supported Mikhail Gorbachev’s proposal of a ‘renewed federation of the sovereign republics’, with only one quarter voting against it.

Matryoshkas escaping. Photo by Didssph on Unsplash.

Yet the optimists insisted that the situation had changed radically. The Soviet Union, they argued, de facto vanished, leaving conservative voters no choice but to accept the fait accompli and acknowledge the new status quo.

In the meantime, the media started reporting the overly optimistic ‘pinky experts’ forecasts that featured Ukraine as arguably the best economically prepared for independence. The spectre of economic prosperity had certainly lured quite a few people who otherwise were not much interested in the sublime ideas of political freedom.

The optimists were right, as 90% of Ukrainian voters (including 54% in Crimea and 84% in the Donbas) approved independence on December 1. Yet the results of the presidential elections held on the same day were ambiguous. In a sense, conservative voters confirmed their political preferences expressed back in March in Gorbachev’s referendum. More than two thirds voted for the incumbent head of the parliament and former communist boss Leonid Kravchuk, and only one quarter supported the leader of the opposition, former political prisoner Viacheslav Chornovil.

It was a clear response to the question about the nature of the impending independence: either it should be a radical break with the communist past and all forms of Sovietism, or a smooth continuity of the existing political practices, institutions and, of course, cadres who – as Joseph Stalin had aptly remarked long before – determine everything.

No Ukrainian peer of Václav Havel or Lech Wałęsa had any chance to win in a heavily Sovietized society; neither Polish nor Czech experiences under foreign rule could match Ukraine’s 300-year ordeal in the Russian empire and the additional 70 years in the Soviet Union.

Ukraine inherited a colonial, opportunistic elite that had been interested primarily in power and property but certainly not in any reforms that would have undermined their dominance. And it inherited a population at large that was neither able nor willing to replace that elite, let alone make it work.

It came as no surprise that the country throughout the 1990s resembled a failed state: hyperinflation broke loose, birth rates plummeted and emigration skyrocketed, and the popular support for national independence fell down, at some points, to barely more than fifty per cent.

Cynicism reigned supreme, and Berthold Brecht’s old dictum (‘zuerst kommt das Fressen und dann die Moral’) was reworded in both Ukrainian and Russian as ‘freedom won’t fill your belly’ and ‘no one would butter his bread with independence’.4

By the end of the decade, the situation had stabilized, relative growth resumed, but these improvements were still too modest to make up for past losses, and too fragmented to usher sustainability. Thirty years after independence, Ukraine remains one of the poorest countries in Europe and one of the most corrupt in the world – at least in the popular perception, as measured by Transparency International.5

A great insistence

As an author, I’ve published several books on Ukraine’s convoluted transition and hundreds of articles where I castigated Ukrainian governments, society and, occasionally, the West that had made its own numerous blunders vis-à-vis Ukraine.

Today, it is certainly not the country I had dreamed about three decades ago, but I have to tame my frustration because four decades ago I would not dare dream about any independent Ukraine whatsoever, at least within my life-span.

This puts me in an awkward position since I have to reconcile my bitterness and justified criticism with a sober recognition of the hard reality of complex path-dependences and low social capacity, of limited competence and the unlimited dullness of political agents.

So, I try to consider the glass rather half-full than half-empty. We are certainly far behind our Baltic or Central European former fellow inmates of the communist camp. But we are certainly far ahead of all the post-Soviet republics since only Ukraine (and a tiny Moldova) retained the democratic system ushered by perestroika – with freedom of speech and assembly, regular multi-party elections and change of government, mass support for democracy and a lasting dedication to Euro-Atlantic integration.

Independence is not only a story of great expectations and disappointments, but also of great insistence, as exercised by a quarter of the population, a minority that has managed to influence the majority-driven post-Soviet politics. It was this committed minority that prevented Ukraine’s backsliding into dictatorship – as it happened in Russia and Belarus.

Admittedly, this insistence at some points required revolutionary upheavals, ultimately costing thousands of human lives and a tenth of Ukraine’s territories occupied by Russia.

This one-quarter minority slowly grew up and matured, making up more than half of the population today and leaving Moscow no chances for Ukraine’s re-Sovietization, or an autocratic turn. They are learning by doing, and I believe that at some point they will learn to make viable coalitions, create responsible governments, and translate nice political programs into reality. To make democracy work, as Robert Putnam famously put it.

A landslide at the imaginary referendum

Every year, on the eve of the Independence Day, pollsters publish sociological surveys that usually contain a staple question about the popular attitude toward national independence: would the respondent support it now in a hypothetical referendum or not?

Nationalists dislike the question, renouncing it as a provocation – they think it would be ‘unfathomable in normal countries’. But Ukraine can hardly become ‘normal’ if it rejects reflection, including sociological. In 2013, before the Russo-Ukrainian war, national independence at an imaginary referendum would have been supported by 61 per cent of respondents, with 28% voting against and 11% undecided.6

To the left, a scene from the 2004 Orange Revolution. Photo via OpenDemocracy from Flickr. To the right: Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv 2017 at night. Photo by Jorge Franganillo from Flickr.

A year later, however, this proportion changed radically: 76 per cent versus 12, and by now the proportion of determined answers reached 82 per cent versus 11. The most significant changes occurred within the specific ethnolinguistic groups.

One of them, ‘Ukrainian-speaking ethnic Ukrainians’ had always been strongly committed to independence, so the changes within this group were modest: from 77 per cent to 91%. ‘Russian-speaking ethnic Ukrainians’ changed their minds more radically – from 54 per cent to 78.

And ‘ethnic Russians’, for the first time ever, made up a solid majority of supporters of Ukraine’s independence: from mere 35% in 2013 to 73% last year.7

Photo by crimea13 from Pixabay.

This largely explains why Ukraine did not break down in 2014, as the Kremlin had expected, – even when the state did really collapse, as the country had neither an army, nor functional police, or a reliable security apparatus. It was primarily volunteers, the multi-ethnic and typically bilingual citizens of Ukraine, who rescued the country and promoted civic identity from a mere political declaration (which it had always been since Ukraine’s independence) to a broadly accepted and emotionally internalized reality.

This is also a response to Putin’s obsessive claim that Ukrainians and Russians are ‘the same people’. The Duce of Moscow draws his bizarre idea on historical myths and antiquated notions of a nation as a community of the same blood and soil, culture and language, history and – quite ridiculously, in the 21st century – religion.

What is missing among these components, as dubious as they are in regard of Ukraine and Russia, is the notion of values, of different political cultures that make the two nations as different and incompatible nowadays as their political predecessors, the historical Moscow tsardom and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had always been.

Photo by Marjan Blan | @marjanblan on Unsplash.

I’m obviously biased, but nowhere have I felt the current of history so intensely and vividly as at home, in Ukraine. This experience can sometimes be as chaotic as awe-inspiring; it can be frustrating and bewildering at the same time, even traumatic, but never boring, never hopeless. Ukraine, I believe, is a great adventure, a great challenge and a great chance.

The charge of ‘bourgeois nationalism’ was a criminal offense, part of ‘anti-Soviet activity and propaganda’, punishable with 2 to 5 years in prison for the first time, 5 to 10 plus exile in Siberia for the second time.

Its Polish equivalent, ‘głową muru nie przebijesz’ means: ‘you cannot bang your head through the wall’.

Samvydav, a.k.a. samizdat in Russian: illegal publications in the Soviet Union disseminated as typewritten carbon-copies or, occasionally, film (analogue) photographs. See in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

‘Свободою ситий не будеш’ and ‘незалежність на хліб не намажеш’ in Ukrainian.

These figures were actually very close to that of the 1991 referendum that gained 90% support from 80% of participants, i.e., 72% of all the adults.

The data come from the recurrent studies by the Rating Sociological Group, 2013, 2014, and 2019. See: http://ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_patriotyzm_082013.2.pdf; http://ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_patriotyzm_082014.pdf; and http://ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_patriotyzm_082019.pdf

Published 23 August 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine (English version); Krytyka (Ukrainian version)

Contributed by Co-published with Krytyka © Mykola Riabchuk / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The climate of hostility in which the assassination attempt on Robert Fico took place has been a feature of Slovak politics for the past two decades. And Fico has played a decisive role in creating it. How the situation in Slovakia came about – and whether it will continue to deteriorate.

Fading hopes for change

Bulgaria and Romania

In Bulgaria and Romania, the EP elections coincide with national elections. Interminable political instability, corruption and socioeconomic tensions all contribute to voter fatigue. With the far right in the ascendant, 9 June could be a watershed.