Amateur photographers offered a range of alternative windows on life in the USSR undercutting the dogmas of socialist realist aesthetics. Bohdan Shumylovych places the Kharkiv School of Photography under Lacan’s psychoanalytic ‘cultural gaze’.

‘In the 1970s and 1980s, Kharkiv photography formed part of the unofficial culture that developed in the Soviet Union during the post-war era’, Ekaterina Diogot writes. ‘But, though unofficial, this culture remained deeply rooted in the socialist economic system.’1

Diogot’s description is shrewdly phrased. Rather than offering a definition of the ‘Kharkiv School’ – which is bound to be self-contradictory – she refers simply to ‘Kharkiv photography’. Time and space are also clearly delineated: we are in the post-war Soviet world. Diogot makes reference to the socialist mode of economic production and, by implication, to the way it created time for leisure activities. The use of free time became a subject of study for Soviet sociologists in the 1960s and was considered a major success for the socialist project.

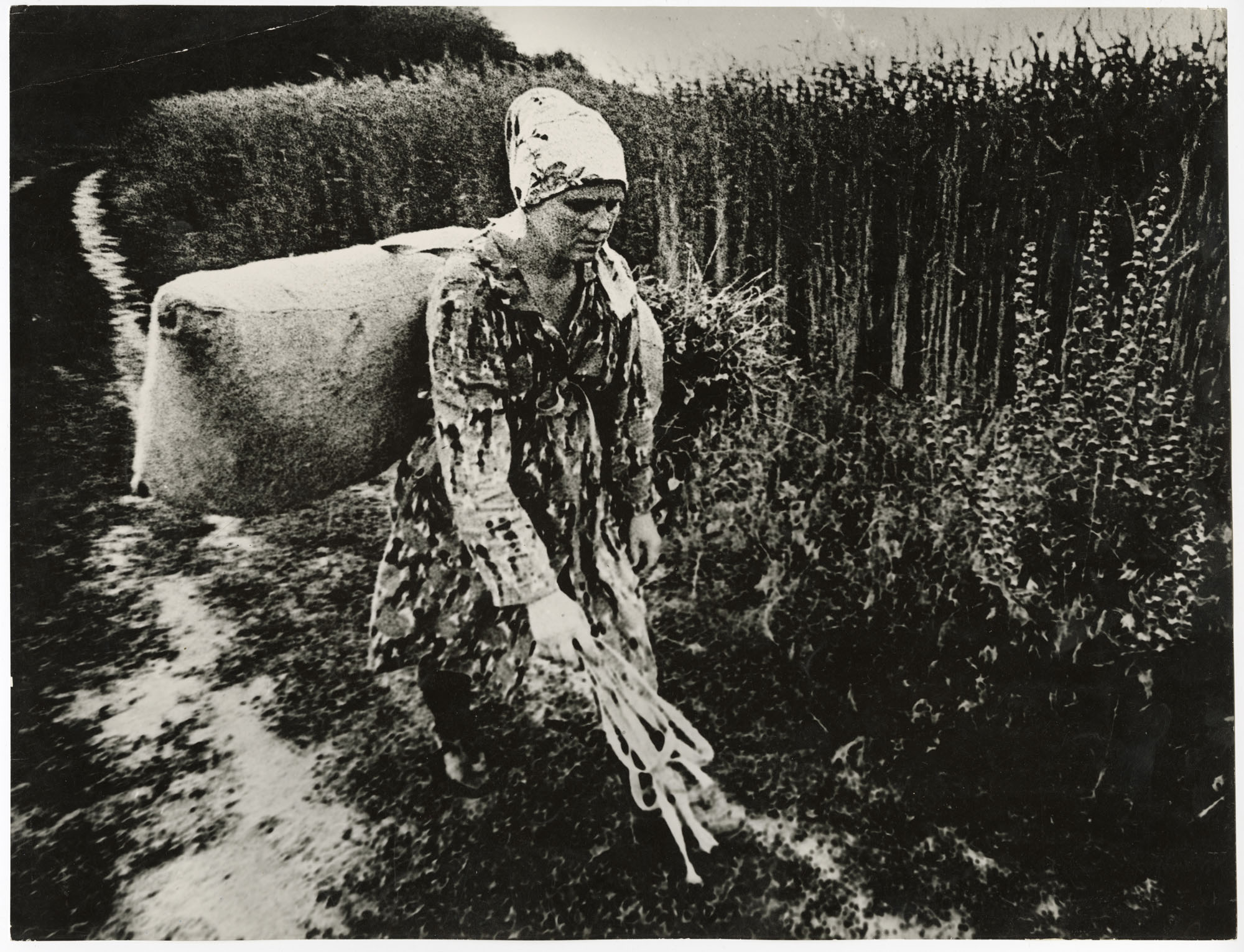

Oleksandr Suprun, Before the Harvest, 1986 (collage, gelatin silver print, 26.5x32cm). Reproduction rights courtesy of © Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography.

The ability to take proper advantage of leisure, to develop oneself and others, to practice culture and art (including photography), was interpreted as a sign of the emergence of the New Soviet Man. His coming was officially proclaimed by the Secretary General of the Central Committee of the CPSU, Leonid Brezhnev, in speeches given in the early 1970s. It was a time when many cities of the Ukrainian SSR, including Kharkiv, saw the formation of informal circles for photographers, who chose to document or ‘represent’ the New Soviet Man in their work.

In the USSR, amateur artists and photographers served as a metaphor for the success of Soviet socialism, and as its embodiment. Gathering without supervision could be a dangerous activity, so photographers had to meet at cultural centres or at work. Members had the opportunity to show their work at photo club exhibitions, which were visited mainly by other club members or representatives of competing groups. External and uninitiated spectators were thought to be superfluous.

Sometimes photographic exhibits were set out in workshops or else shown informally to colleagues, as a taste of what ‘authentic’ art might be. Amateur photo clubs also made it possible to subscribe to photographic magazines from other socialist countries, and images published in these magazines often had considerable impact on the work of photographers exhibiting at a local level.

In addition to the shows occasionally organized by photography clubs, there were, of course, official republican and all-Union exhibitions. One founder of the Kharkiv photo group Vremya, Jury Rupin, recalls: ‘These were so formal, both in subject matter and in their requirements, that trying to participate in them with the kind of works I had, would have been sheer foolishness.’2

Virtually all photographers in Soviet Ukraine who wanted to create original photographs in line with their own artistic ideas, were up against censorship all the time, Rupin says. They knew there was no point trying to participate in photo exhibitions organized by government agencies in the Ukrainian republic. Official Soviet photography had clear rules about expression, topics to be presented and quality of photography. Since the Soviet Ukrainian republic also had a notably high level of censorship, it was often easier to show your work outside Ukraine than at home.

Members of non-professional photography clubs were not supposed to compete with professional photographers, who got income and status from their work. Amateurs functioned in a different zone. They observed the world of Soviet cities – the everyday lives of ordinary people on the one hand and practiced aesthetic experimentation on the other. This was photographic subject matter for which no one in the USSR would expect to pay, a kind of visual ‘refuse’.

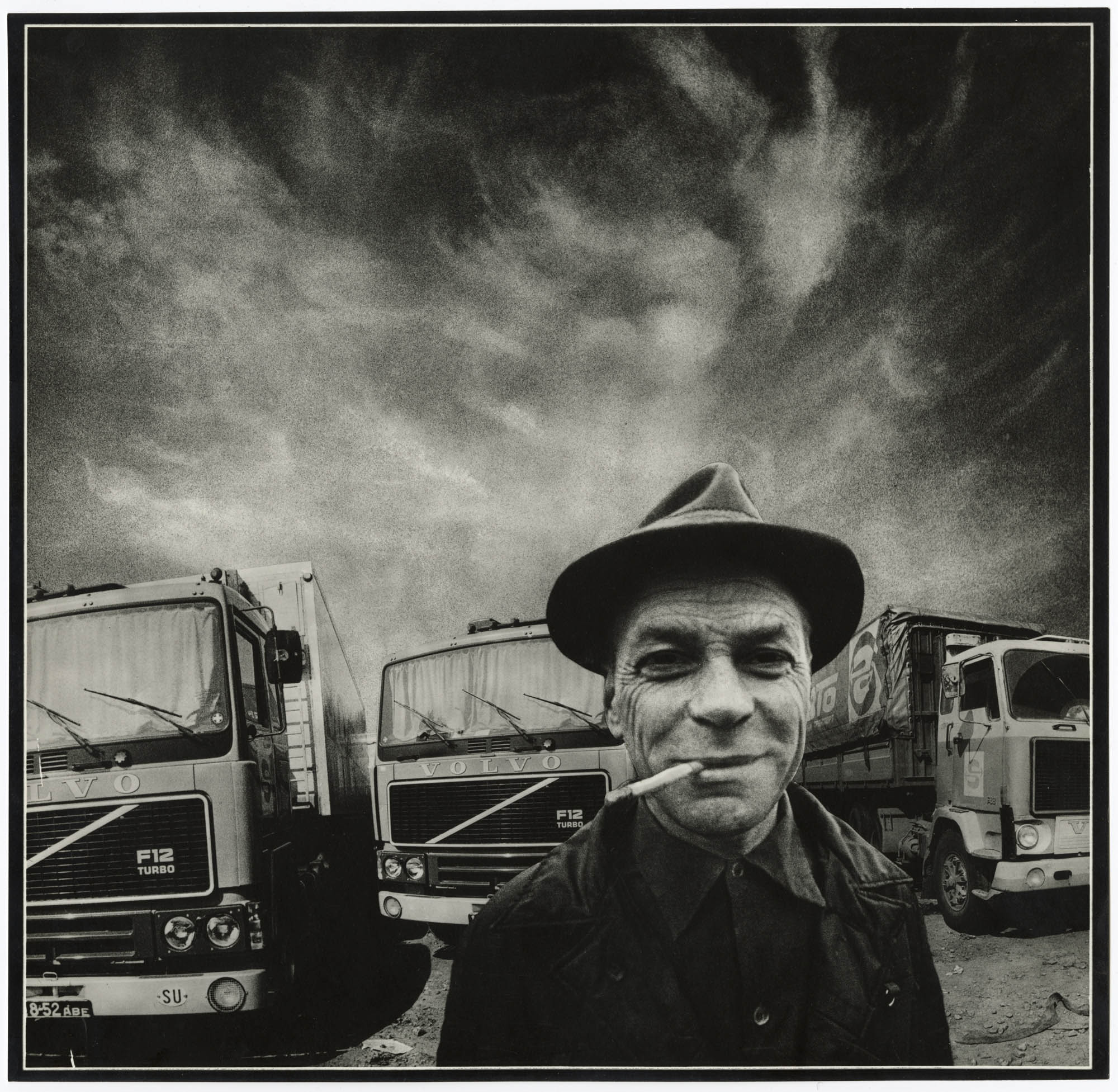

Oleksander Suprun, Stop on the road, 1987 (collage, gelatin silver print, 26.8x26cm). Reproduction rights courtesy of © Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography.

As foci, these subjects tended to lead to debate about photography as an art form, rather than to discourse on street or documentary photography. Hence the widespread use by Soviet amateur photographers of superimposed photographs or slides, montage and collage. They also experimented with colour and chemical processes including posterization or toning. Techniques such as this were intended to reveal the author’s subjective gaze, which was often provocative and, at times, aggressive.

On the other hand, amateur photography was not bound by socialist realist aesthetics and, to some degree, could disregard official judgements on photographic quality. According to Rupin, photographers seeking to create art photography tried to separate the spirit of their work from existing concepts of excellence. They frequently created works that appeared to disregard the very notion of quality, and thereby emphasized the absurdity of any aspiration to achieve images of high photographic value.

Evgeniy Pavlov, a co-creator of Soviet ‘Kharkiv photography’, has commented on the supposed subjectivity of amateur photographers. ‘One common feature of the Kharkiv school is a harsher form of expression’, he writes. ‘At times it can be brutal, outrageous or violent.’3

Pavlov argues that the subjectivity of photography lies in its individual or artistic nature, which is the antithesis of the documentary form.

In times when fantasy was not permitted in art, imagination seemed richer than life. Yet it goes without saying that life remains more powerful than any artist, especially where photography is concerned. A straightforward household documentary photo increases in value as the years go by. This is not always true of subjective forms of expression, because these depart from real life. Years pass, and what a documentary photographer has chronicled is no more. And then it turns out that life shots hold far more significance for people than our ‘subjectivity’.4

It is evident that, for Pavlov, ‘subjective expression’ implies a world of dreams and fantasy which lies outside the objective vision of documentary photography. My own attempt to analyze the subjectivity of Kharkiv photography will focus not just on the point of view of the photographer but also on the perspective of the new Soviet Man invented by the communist project.

Broken pictures

Soviet modernization sought to expand the visual component in culture. Vision or the position of an observer – that is, of a person with visual experience – played an important role in forming the Soviet citizen. In the USSR, audience perception was highly politicized and the Soviet vision of the world determined the shape of all objects designed for public viewing. Cultural policy secured the formation of a specific visual ‘lexicon’, which came to be reflected in fine art, the structure and stylistics of images, and in posters. Consumers of this array of visual propaganda were invited collectively to participate in viewing achievement and progress. It was a process designed to stabilize the approved worldview in the public mind.

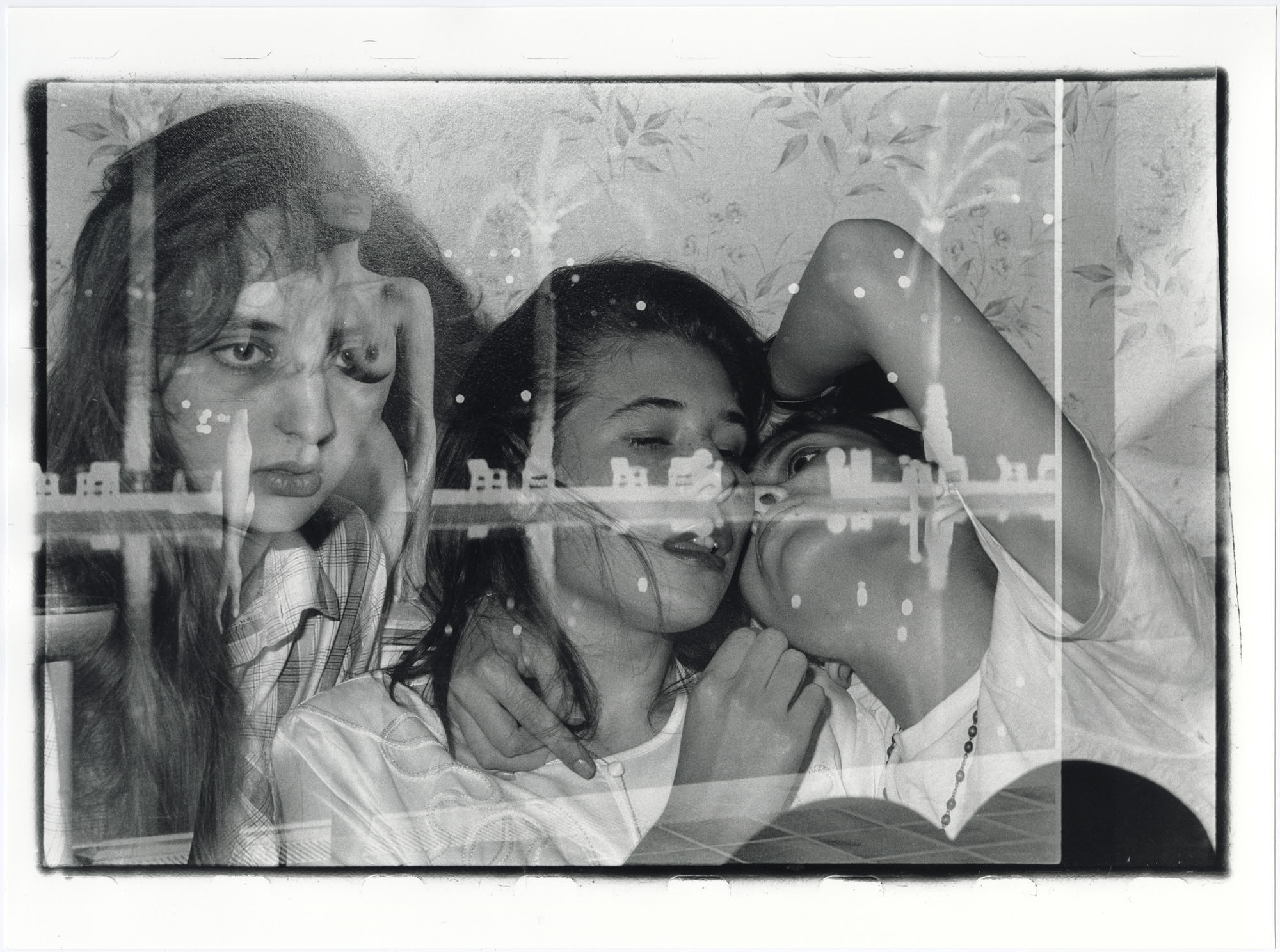

Roman Pyatkovka, Untitled, from the series Wrong photography, 1986 (gelatin silver print 2019, overlay, 1/5, 29.2×39.2cm). Reproduction rights courtesy of © Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography.

The Soviet project devised a ‘correct’, officially sanctioned visuality with the purpose of creating a kind of fairy tale or utopia. Evgeniy Dobrenko argues that, as a political and aesthetic project, Stalin’s socialist realism was not the ‘embellishment’ or ‘varnishing’ of reality (words Nikita Khrushchev used to describe Stalinist musicals)5 but a replacement of existing reality by something new.6 Substitution holds an important social function in the cultural sphere, insofar as culture functions as a ‘dream factory’.

In the Soviet case, the intention was to replace actual reality with an imaginary reality. The idea was not to change the future but to present the future as a reality in the here and now. In this sense, official Soviet photography was paradoxical: it served as a tool for representing the socialist world in an objective way, yet it worked at the level of idealized imagination. In this mode of visuality, Soviet people were shown from the perspective of an ideal future: they had no flaws. Unofficial, amateur photography saw Soviet subjects from a very different angle, however.

Researchers into Kharkiv photography often note that many representatives of this ‘school’ became innovators who contributed to the decline of the established Soviet visual aesthetic. One thing united them as a group: the rejection of officially promoted artistic norms. Kharkiv photographers saw the dominant mode of visuality as routine and mediocre, and considered the socialist realist utopia to be disconnected from real life. Their discussions on visual art produced new techniques and aesthetic approaches, including the idea that photography should disturb, shock or ‘strike’ the viewer.

Kharkiv photographers understood that photography could not function in the same way as a painting. Even though, in both cases, the picture is two-dimensional, the impact is necessarily different. Photography therefore had to seek its own language – it was, after all, to be the medium of the future! Or so the photographers of the time believed.

It is sometimes argued that Kharkiv photographers creatively transformed the legacy of Dadaism and Soviet constructivism through the use of photo collage and photomontage7 – those forgotten traditions of Soviet visual art dating back to the 1920s and 1930s. A special place in their experiments was occupied by the search for a new artistic language: a fundamentally different means of expression that would bring photography as close as possible to fine art.

Academic research sometimes compares the imaginative vision of Kharkiv photographers to the European and Soviet avant-garde, which harnessed ideas promoted by the German philosopher and literary critic Friedrich Theodor Fischer (1807-1887). Fischer recommended replacing the concept of mimesis (representation or reflection) with the concept of empathy,8 meaning the artist should ‘follow not the subject, but feelings that arise when perceiving the subject’.9 The image would then become not representative but universal, and the picture could be transformed into a work of art. This method is characteristic of expressionist art associated with Van Gogh and many artists working in Germany. It’s scarcely surprising that Evgeniy Pavlov really admired the work of Otto Dix!

In Kharkiv circles, the photographic ‘shock’ or ‘blow’ was widely understood in terms of its immediate effect. This was intended to resemble an impact, surprising the viewer and enhancing the effect of the picture. The art photographer and writer Jury Rupin pointed out in his memoirs that there existed a consensus among Kharkiv photographers that an image could be ‘artistic’, and hence subjective, in just two instances: when the photo was staged and when it was transformed into graphic art. In addition to particular subjects and themes that were ‘shown’ and ‘seen’, the effect of a blow could be achieved through collage and montage.

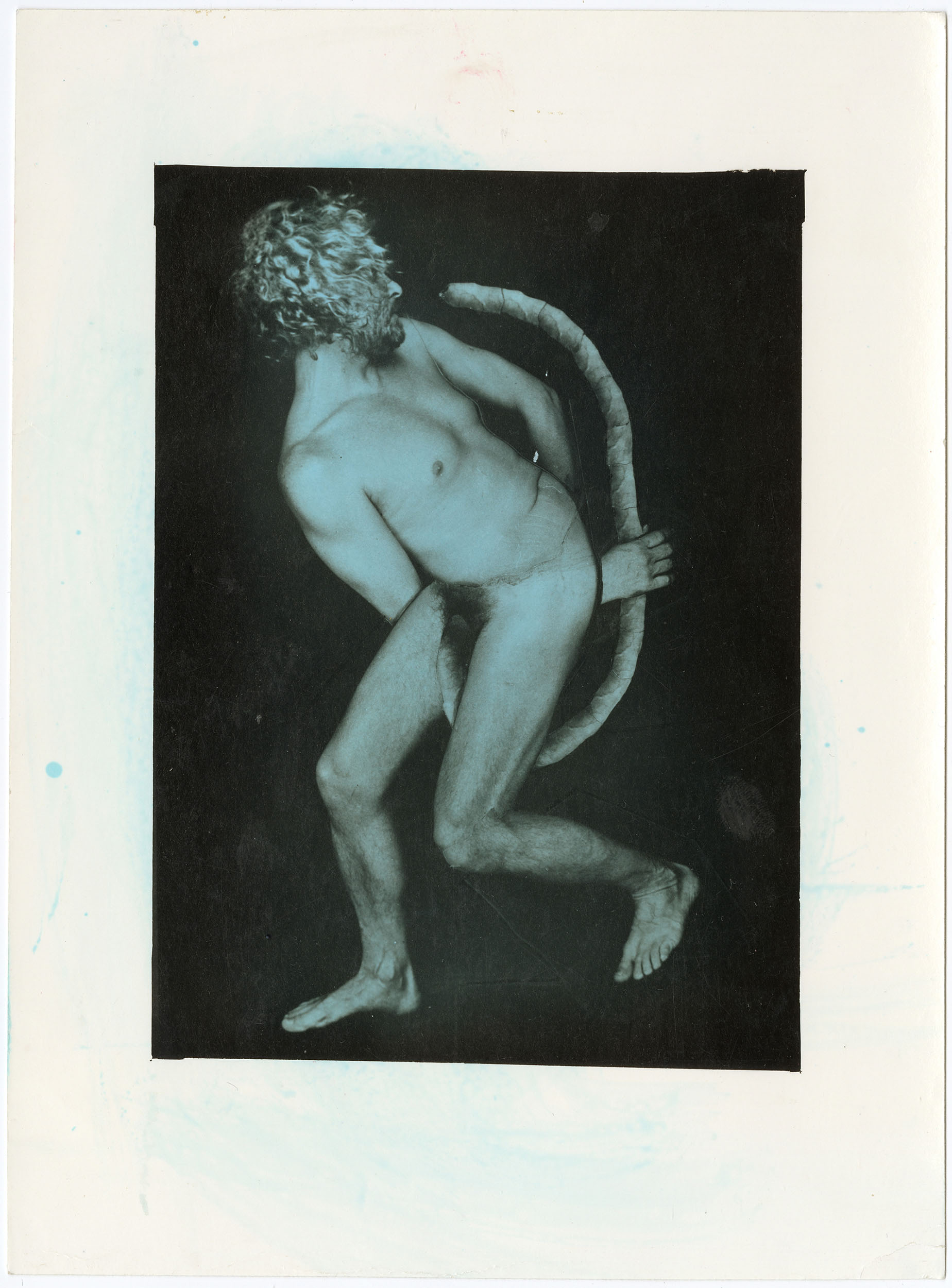

Sergiy Solonsky, Untitled, from the Bestiary series, mid-1990s (photomontage, gelatin silver print, toning, 20x15cm). Reproduction rights courtesy of © Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography.

This feature of Kharkiv photography was seen by some as a revival of Dadaist aesthetics. The term ‘photomontage’ took root in European languages from May 1920, when the first Dadaist fair took place in Berlin. At the time the word ‘montage’ was used to denote techniques used in three types of art: cinema, fine art/photography and theatre. As the filmmaker Lev Kuleshov noted, the term soon came to refer not just to a specific feature of cinematic language but equally to similar devices applied in other art forms (such as cinema and photography).

Yet the aesthetics of impact, invented by Kharkiv photographers in the 1970s, had been envisioned as early as the 1930s by German and Soviet artists. In 1931, Soviet artist Gustav Klutsis identified the following features and methods of montage: a) favouring diverse scales, rather than using traditional limited perspective, to enhance impact [udarnyi moment]; b) introducing contrasting colours and shapes; c) freeing up or ‘carving out’ a photographic subject from an inert background and presenting it in a strong shade of colour (when achromatic colour is matched with chromatic, an effect of extreme contrast is achieved).10

In a work of art which uses one or more compositional techniques, the ‘connections’ (suture) of montage shapes acquire a special role. They reveal not only the heterogeneous nature of the work but also its underlying construction. In the broadest sense, montage or collage both assume that the world has been cut into visual fragments and rearranged in a new order. This ‘remake’ is visible to the viewer or the listener while often also becoming a constituent feature of the artwork in question.

Some philosophers even argue that mimesis, as a representation of reality, involves the rupture of any ‘frozen’ visual unity and that montage is a compositional method of re-structuring this fragmentation.11 Montage may be described, therefore, as a new form of mimesis, or an intellectual re-creation of the idea of imitative representation. It reveals the ‘true’ and hidden meaning of things, rather than their external features.12

One of the experimental methods of montage used by Kharkiv photographers was image overlay – a technique applied by Oleg Maliovany and Boris Mikhailov. By superimposing two different images, photographers created a multifaceted work, expanding the boundaries of photography and transforming the photographic image into an art object. This approach also helped overcome the dominant aesthetics of official Soviet photography. Edited, superimposed images revealed an urge to transform the mimetic essence of photography, and overcome its technical and aesthetic limitations.

Image montage can often end up appearing logically paradoxical and aesthetically grotesque. It may merge external impressions with images linked to emotional or psychological experience, and the inner life. This feature of the technique once again undermines traditional notions of imitative representation.

Within the framework of conventional mimesis, descriptions of the outer and inner worlds are organized very differently. Historically, as art develops, this dichotomy appears less stark, but the depiction of inner experience in terms of images from the outer world is particularly characteristic of the modernist period. It is also an aesthetic technique that features repeatedly in Kharkiv photography.

Looking at the self

The montage and collage, which distinguish Kharkiv photography, not only interpreted the Soviet subject from angles disregarded by official photography but also allowed photographers to discover their own subjectivity. This surpassed the idea of subjectivity as artistry or fantasy, and the limited sense in which Evgeniy Pavlov used the word. Jacques Lacan’s explanation of human subjectivity is helpful in this context. Lacan addresses the problem of the photographic image in an essay entitled ‘What is an image?’ included in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. In particular, he highlights the concept of the ‘cultural gaze’ – an important and pervasive idea in his writing.

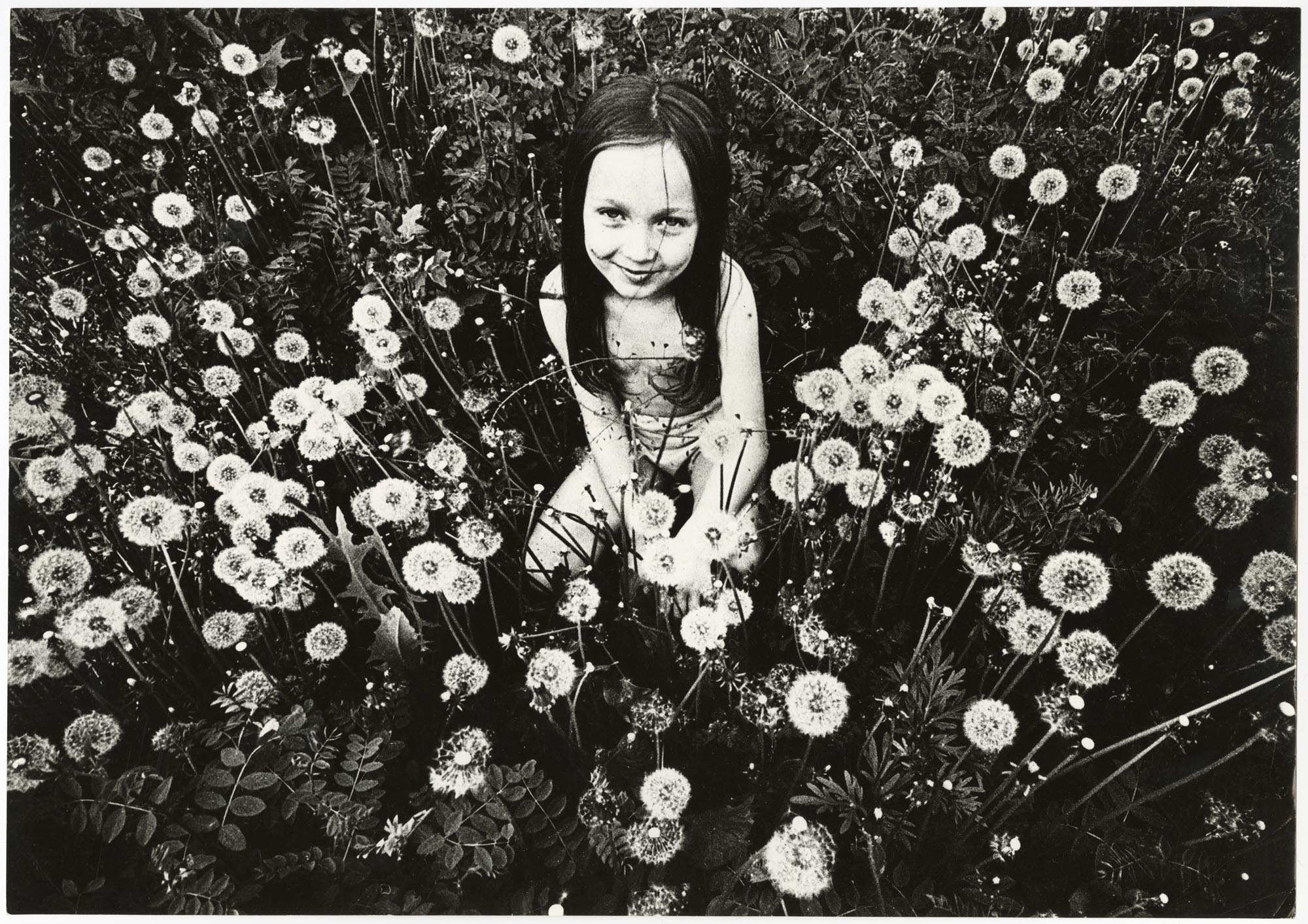

Anatoliy Makiyenko, Dandelion, 1974

(gelatin silver print, 28.5×40.5cm). Reproduction rights courtesy of © Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography.

Following Freud, Lacan describes the so-called ‘mirror stage’ of psychological development, which explains the transformation that occurs within a subject when he or she assumes a certain image or ‘imago’. Lacan’s theory is based on an aspect of human behavior which relates to the findings of comparative psychology.

Even at an early age, looking in the mirror, a child has the capacity to recognize the reflection she sees there as her own image. The theory calls into question the Cartesian thesis that the human being exists only when he or she thinks, that is to say functions using language or text. In point of fact, humans unconsciously operate the mechanisms of visuality that construct their personalities long before they acquire speech. At the mirror stage, a child has the opportunity to break away from the symbiotic relationship with her mother in order to comprehend her individuality. The child recognizes herself, a split occurs between self and image, and from then on any imaginary construction can enter her divided sense of who she is.

Ideologies work within the gap between self and image. They construct visual rules or expectations to identify individual subjects with the image that is desired. In capitalism, this could be the Marlboro cowboy; in Soviet socialism it was the conscientious, selfless proletarian.Either the individual creates a mask for himself and unconsciously constructs subjectivity, or the imaginary mask is imposed by culture. As human beings, we are subject to the gaze of governments, cultures and other people – creatures to be observed in the theatre of the world around us! ‘I see myself seeing myself’, Lacan wrote13, which is why Soviet subjectivity was not ‘historical objectivity’ but rather a kind of prosthesis, an artificial limb that helped people cope with reality.

For Lacan, subjectivity is a device, a fictional narrative reflecting the urge to explain the world and find one’s place in it. But the narrative has a price. In developing a device by which to identify herself, the subject ends up experiencing a sense of absence where the imago (the unconscious, idealized model for creating identity) appears as an unattainable ideal.

Lacan therefore proposes an ethic of doubt, a model of subjectivity that opposes any form of certainty. In photography, the person portrayed will perceive herself in two opposing fields: I am the one who is me, and I am the one who acts as someone else. The separation between the mirror image and the internal consciousness of self is never clear-cut, and any adult is subject to the power of the imago or imagined perception of who she is.

Anatolii Makyienko, A Hard Day (In the Field), 1974 (gelatin silver print, FDP method, 30x39cm). Reproduction rights courtesy of © Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography.

A photo image is to an adult, what a mirror is to a very young child. When looking at a photograph, identification with what Lacan calls the ideal-I or imago occurs through a thought pattern that could be summarized as follows: I know that what I see is myself, and I also know that it cannot be me because I am looking at a photograph.

At this stage a rift takes place, and when this happens one is liable to identify with any projection appearing at the point of intersection between gaze and representation. For we are formed as identities separate from ourselves. At the individual level, the dichotomy between the inner self and the external, photographed image is experienced as a basic psychological tension.

By establishing visual models to guide behaviour, the Soviet regime constructed its own citizens while offering them the illusion of an ideal, utopian future. It was as if official Soviet photographs and visuals had fabricated a dream that acted as an antidote on the cogito.

A dream is something shown, it is not the same as the gaze. In a dream state, something leads us on; we don’t even realize we’re dreaming. A dream is not a representation, it is linked to the unconscious. As in a mirror, when I am photographed (or photo-graphed) the subject is constructed when he or she becomes visible. By dividing the word photo-graphy in two, Lacan seems to split the subject who is formed as she gazes at the reflection of her own image in a photograph, like in a mirror.

Historians or anthropologists discuss the nature of Soviet subjectivity through texts, that is to say through language, speech and writing. Like language, the gaze can act as a paradigm of human experience. For Lacan, looking and the gaze are separate and distinct, just as for Ferdinand de Saussure speaking and language remain distinct. Looking, like speaking, is a performative process whereas the gaze indicates structure and meaning.

If the Soviet subject has been visually constructed, then her photograph may act as a trap for the gaze. The photo has the power to dismantle the magic of the image. By creating an alternative dream or mirage through photography and montage, Kharkiv photographers discovered a capacity to reset reality. Their subject could reconstruct herself through a dream image.

This approach is clearly evident in Boris Mikhailov’s Private Series (1960s) as well as his Red Series (1968-75).14 It is also reflected in Roman Pyatkovka’s ‘communal body’ (1980s),15 in portraits by Jury Rupin16 and Oleg Maliovany (‘demonstration’, 1978-85),17 in Sergiy Solonsky’s ‘bestiaries’ (1990s) and especially in a well-known project by the Fast Reaction Group18 entitled ‘If I were a German’ (1994).

For photographers, the sense that they were seeing themselves in their Soviet subjects evoked differing blends of pleasure and uncertainty. Their identification with ordinary Soviet people was an open wound as much as a protective screen. Both photographer or viewer adopted an image that permitted a split between the self and the other projected self. It became possible ‘to see myself seeing myself’.19 These photographic flights of fancy, realized through technical and visual experiment, made it possible to rethink the Soviet subject. Above all, however, they gave photographers the opportunity to re-examine themselves as people who, while being cultural ‘outsiders’, nevertheless remained inextricably bound to the Soviet world.

This article was written for a project entitled ‘The Kharkiv School of Photography: From Soviet Censorship to the New Aesthetic’ which forms part of the Ukrainian Institute’s ‘Ukraine Everywhere’ programme.

K. Diohot “Proizvodstvo svobodnoho vremeni” [The production of free time], Journal 5.6, No. 7, May 2012, http://www.magazine56.com.ua/images/2013/02/5.6-Kharkiv.comp_.pdf

Jury.Rupin, “Dnevnik photographa: tridtsat’ let spustia” [A photographer’s diary: thirty years after], 2007, http://photo-element.ru/story/rupin-2/rupin-2.html?fbclid=IwAR39IRnRn7KibBXxY-d4xQElAiIoQ6By-ipUoml238disNAUVsgkZvspYuo

Anton Shebetko, Evheniy Pavlov, “Zhizn’ kruche samykh bogatykh fantazii” [Life is greater than any fantasy], 18 October 2016, https://birdinflight.com/ru/portret/20161018-eugeniy-pavlov-interview-harkovskaya-shkola-photographiyi.html?fbclid=IwAR2zGekfdRfAFrsu3aSNnAX-E1zjcaQ-NJb_wixSiiFB8D6GSBEOaU8Yybg

Ibid.

Naumov V.P., “K istorii sekretnoho doklada N.S. Khrushcheva na XX siezde KPSS”, [On the history of the secret speech of N.S.Khrushchev at the 20th Congress of the CPSU], Novaia i noveishaia istoriia [Modern and Recent History], 4/1966

Dobrenko, E., “Socialist Realism” in The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Russian Literature, Cambridge University Press, 2011. See also: Dobrenko E., Political Economy of Socialist Realism, Yale University Press, 2007.

In this text, I do not distinguish between photomontage and montage and often treat them as analogous to collage. Collage as a technique originated among Cubist artists and involved the creation of images from elements of other images. For Dadaists, photo-montage (similar to installation) was a technique of creating a new aesthetic effect through a combination of separate images. We can think of a serial photo, or a combination of photos as an example of montage, and combining elements into one image as a collage. However, in both cases these distinctions have the same strategy of ‘synthesis’ – creating a new form from existing elements.

German: die Einfühlung

Ilya Kukulin, “Mashiny zashumevshego vremeni: kak sovetskii montazh stal metodom neofitsialnoi kultury” [Machines in noisy times: how Soviet montage became a technique used in unofficial culture], Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2015 (electronic publication)

A. Fomenko, Montazh, faktografiia, epos: proizvodstvennoie dvizheniie i fotografiia [Montage, factography and the epic: the production movement and photography], St. Petersburg University Publishing House, 2007, p.318

Artemy Magun, “Negativity (Dis)embodied: Philippe Lacoue Labarthe and Theodor W. Adorno on Mimesis”, New German Critique 118, Vol. 40, 1/2013

See the following volume dedicated to the aesthetic theory and theory of mimesis of Theodor Adorno: Tom Huhn and Lambert Zuidervaart (eds.), The Semblance of Subjectivity: Essays on Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory, http://cognet.mit.edu/book/semblance-of-subjectivity

Peter Hobbs, “The Image Before Me”, Invisible Culture, 7, 20 March 2004, https://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/the-image-before-me/

See some works of Boris Mikhailov at: https://www.moksop.org/en/art/artists/boris-mikhailov

O. Osadcha, “Roman Pyatkovka: polovi doslidzhennia ‘komunalnoho’ tila” [Roman Pyatkovka : field research on the ‘communal’ body], 17 August 2019, https://www.moksop.org/roman-piatkovka-pol-ovi-doslidzhennia-komunal-noho-tila

N. Bernar-Kovalchuk, “Fotohrafichni tropy Yuriia Rupina” [The photographic paths of Jury Rupin], 6 March 2019, https://www.moksop.org/fotohrafichni-tropy-yuriia-rupina

N. Bernar-Kovalchuk, “Vid sotsrealizmu do zirok: ekvidensyty ta kolazhi Oleha Malovanoho” [From socialism to the stars: Oleg Maliovany’s equidensities and collages], 24 May 2020, https://www.moksop.org/vid-sotsrealizmu-do-zirok-ekvidensyty-ta-kolazhi-oleha-mal-ovanoho

The group included Boris Mikhailov, Sergey Bratkov, Sergiy Solonsky and Vita Mikhailov.

Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis (Routledge, 2018), 80.

Published 18 January 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by The Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) © Bohdan Shumylovych / The Kharkiv School of Photography / Ukraine Institute / The Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Russia’s orbit

Osteuropa 4/2024

Repression, murder, war: on the logic driving the Putin regime toward ever-greater excesses of violence. Featuring Yuri Andrukhovych on the Russian colonial empire – the only ever to have tried to reconquer a former possession. Also: articles on Navalny, and on what next for Georgia?

The difference between knowing from distance that war is being waged and living that reality couldn’t be more extreme. But can awareness of multiple repercussions turn protective disassociation from violence into active solidarity? ‘The Most Documented War’ symposium in Lviv, Ukraine, provides valuable pointers regarding engagement and responsibility.