Kyiv: A love letter

For Oksana Forostyna, memories of Maidan mingle with accounts of her grandmother’s life in Kyiv before and during World War Two. Recollections of her own search for happiness in her adoptive city lead to more universal questions about the possibility of freedom and love amidst conflict and war.

I know the exact moment when I finally realized how surreal it all was: 2 a.m. one December night in 2013. We had just listened to a short introduction to basic survival skills: when the Berkut (special police officers) pursue you, mind your neck; when being beaten, fall on your right side to protect your liver, you can only live twenty minutes without medical assistance if it’s injured… This was the kind of information we’d need for the next few hours on night watch in the very centre of this large European city – the middle of Maidan, the main square, near the National Post Office headquarters.

The location can be described as, well… aesthetically ambiguous, especially after the square was redeveloped during the 2000s and subterranean shopping malls added. This was a predictable development for Kyiv, a city struggling to acquire its status as Ukraine’s new capital. The whole project, with its glass and steel facades, echoed the 1990s renovation of Manezhnaya Square in Moscow. But how did it come to pass that there was a barricade here, on the Maidan, the very place I used to run through (as fast as you can ‘run’ in heels) just a few months previously?

When I was little, Kyiv was a city that my grandmother hesitated to return to: ‘It’s all different now. I don’t want to see it.’

Kyiv was then the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and, from where we lived in Lviv, the closest ‘major’ city. Yet even from Lviv, one of the Soviet Union’s major westerly cities, Kyiv seemed slightly provincial and uninteresting, at least in the milieu in which I grew up. My parents had to go to Moscow at least once a month. Although they didn’t like it, Moscow was useful and necessary, Kyiv was not. Why would anyone go to Kyiv?

We had a set of postcards showing the sights of Soviet Kyiv, printed in 1983, I guess. ‘It’s all new’, my grandma said, looking at the photo of Khreshchatyk, one of the main streets in Kyiv, which had been rebuilt after the war in the ‘Stalinist Empire style’. ‘If I go, I will know nothing’, she added.

Khreshchatyk was familiar to me from official images in my Soviet textbooks and from my grandma’s scrappy, tangled stories. The official version and my grandmother’s clashed completely.

Her Khreshchatyk vanished when the Nazi army occupied Kyiv. Anticipating what was to come, the NKVD (Soviet secret police) rigged the buildings on all the main streets with explosives, including Prorizna, where my grandma lived in an apartment belonging to her stepmother. When the Germans took the city in 1941, Red partisans and NKVD officers blew up the buildings. My grandmother and her stepmother managed to grab some documents before leaving the apartment. The building exploded before their eyes.

Khreshchatyk street in Kiev, 1942. Photo source: Wiki Commons

She always used to recall: ‘Just before the war began, I had a silver fox collar coat, shoes with three-inch heels, and a crêpe-de-chine dress all made for me. You don’t have this kind of crêpe-de-chine now. You could roll up a dress, put it in your handbag, and then change after work for the theatre, it looked perfect without ironing.’

I don’t quite remember whether it was directly after her home was destroyed, or after she fortunately avoided forced labour in Germany, when a Nazi guard pushed her away from the queue in front of a van. (I still wonder if this was an instance of human attraction and empathy, or because of an idiosyncrasy in his Nazi worldview, which meant he believed a beautiful specimen should have a chance to survive.) Anyway, the story was that she walked fifty kilometres in those heels to relatives in Fastiv, a small town near Kyiv. But the post-war years were difficult and so she moved to the small western Ukrainian town of Drohobych in 1946 and then to Lviv.

It now seems to me that she repeated these words most often, or at least I remember them best: ‘A silver fox collar coat, shoes with three-inch heels, and a crêpe-de-chine dress.’ A link to her happy pre-war life in Kyiv.

I don’t remember her being pretty and I was too young to recognize the vestiges of her beauty in old age. Neither did she have any pre-war photos. I just knew her beauty saved her life at least once.

Still, I was puzzled as to how happy her life really was.

I moved to Kyiv in 2011, though I already had past experience of the city – my parents lived in the new capital in the late 1990s, and lately I had been hanging out there constantly due to my job. Although it had been possible to move from Lviv to Kiev during Soviet times, the more ambitious people chose Moscow instead. This changed after 1991. As Ukraine’s young democracy started to gain a foothold and the country steadily shrugged off its Soviet past, Kyiv became friendlier, more opportunities opened up, and more politicians, journalists, businesspeople, musicians felt encouraged to set up in the capital.

My case was just the opposite. Viktor Yanukovych, the notorious, cartoonish pro-Putin politician with a criminal past (and present), usurped presidential power in 2010. We expected to enter a new Ice Age. All the evidence pointed to the traditionally anti-Soviet and pro-Western Lviv as being a far better and safer place to live in times of decay and repression, a kind of refuge. In the worst-case scenario, you could at least rely on a cosy form of corruption that the city had inherited, a special kind of solidarity against the imperial centre. During the anti-presidential protests in 2001, an opposition organization in Lviv lost access to its own database and the city’s police shared a list of young activists with them, so they could track down students who had been arrested in Kyiv.

I came to Kyiv not because of a new job – I just switched to my company’s Kyiv office – but in search of happiness. As it happened, though, I did get one a new job just weeks after arriving.

The first year I used to stop at Prorizna Street on my way back from the office to have a cigarette or two, roughly where my grandma’s home was, the one that was blown up before her eyes.

A huge fire followed the explosions. The NKVD and partisans did everything they could to prevent the Nazis who controlled the city from fighting the fire. This included cutting off the water supply from the Dnipro River. When in 2014 the Yanukovych regime’s final plan of attack was revealed, the similarities were shocking: water and electricity supplies to central Kyiv were cut off, we were surrounded with fire and darkness and eliminated from the city – not to forget that the regime branded us ‘Ukrainian fascists’. Two generations later, there we were again, with ash in our hair and soot on our faces.

During the warm summer nights three years before Maidan, just as my Kyiv life began, I often stood where my grandma lived when her Kyiv life ended. Of all what drew to a close. Given everything that she told me, it seemed that those days were the happiest of her life: she was young and beautiful, she went on dates. ‘A few Jews were courting me’, she used to tell me proudly as if by way of feminine validation, as if to say, ‘Boy, I was hot!’ I’m not sure about the timeline. Maybe those happy years were directly after her father and brother came back from East Siberia in 1939; both had been arrested, tortured and imprisoned in a labour camp in 1937, but released two years later during the so called ‘Beria Amnesty’. She also witnessed the Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932 and 1933, as well as the Babyn Yar massacre of 1941. I first learned of both tragedies from her, as they simply hadn’t featured in my Soviet school education. Those were the most terrifying years of Stalinist repression, yet she managed to find some joy in this city.

Decades later, so did I. The scale on which the system then operated is of course incomparable with that of the Stalin era. Nonetheless, in 2011 political activists were persecuted, arrested and terrified. Businesses were blackmailed and raided. All state institutions were hijacked by the so-called ‘Family’ (that is, members of the Yanukovych family and its associates). Every morning and every evening, the traffic was paralysed when the presidential cortege crossed the city.

Yet it was the same kind of big city life as in any other European capital with friends, dates and parties, picnics in the park and concerts, being in love, being broke. One of the few differences for me was being permanently conscious that we may lose what little freedom we still had at any moment.

I was happy. I got my dream job at the best intellectual magazine in the country. I had friends. I rented a beautiful small apartment one stop from the Maidan, in Podil, quite a hip area even back then (and even trendier now), where everyone used to party. Someone might call late at night and you just went out there and then. My 33 was the new 19.

Yet it still felt very precarious, at least to me. I deliberately tried not to acquire any of the accoutrements of home, as it didn’t feel like a good time to settle down. Actually, I was sure that some kind of revolt lay ahead, and I was almost certain that it wouldn’t be pretty. I sensed the future would look much more like Belarus than post-1989 Poland.

Once, my lover, an especially witty guy, answered my polite first-time question ‘Is everything okay?’ along the lines of: ‘Well… Yulia is in prison…’ – referring to the politician Yulia Tymoshenko. We both immediately burst into hysterical laugher. These cynical eastern Europeans, you know, with their dark sense of humour. But this also brought up a very old-fashioned issue: Can you have sex when someone is imprisoned? Can you go on dates and wear heels and silk dresses? How many generations of lovers in this country must exchange their grandparents’ prison stories (about working in the prisons or doing time in them, sometimes both) as pillow talk?

I was making notes for my second novel (the first one was about to be published), which I knew would be about the forthcoming uprising. I tried to firm up its blurred lines but made little progress. It was like trying to remember a dream in the morning, a dream both marvellous and terrifying.

Not that I was making it all up. We (by ‘we’ I mean a few thousand people, mostly political activists, lawyers, journalists, writers, whom I dared to consider as ‘my Kyiv’ back then) protested here and there and, at the end of May 2012, a significant non-violent civic protest movement formed just down the road from my home. The activists occupied Hostynnyj Dvir, a public building that was then raided by a developer allied with the oligarchs. Its large courtyard was like an island, the building like a fortress, it was unlike anything else in the city. Later they would say it was a rehearsal, a year and a half before Maidan: with night shifts and campfires, concerts, happenings and poetry readings, attacks by titushki (paid thugs), and ideological clashes between activists. At times, felt surreal too. Another protest against the legislative assault on the Ukrainian language was staged around the same time in the city centre at the beginning of Khreshchatyk.

At the end of March 2013, just as it seemed that spring had already arrived, a huge snow storm hit Kyiv. The traffic came to a standstill, public transport services were overwhelmed, thousands of people stuck in their cars all night. Many others came out onto the streets to help those trapped in the snow. ‘That was a kind of a rehearsal’, one of the HelpKyiv! organizers would say later. It was the night on which the first outlines of future volunteer networks emerged.

The next morning, you had to walk through narrow corridors between a meter-high layer of snow. Young people were snowboarding and skiing on the hills in the centre of the city. Some hooked their snowboards to cars. The city was full of pretty young things in bright ski suits, the sunny streets smelled of restaurant grills and mulled wine. The unusually empty central streets took on the atmosphere of a ski resort. Suddenly, they were overwhelmingly populated by people rather than cars, people looking directly at one another, somehow happy to have survived the storm. We didn’t know that many of us would spend the next winter in ski trousers. Looking back, it seemed like an ironic preview of what was to come.

The latest song by the extremely popular Russian singer Zemfira wafted through the moist air: ‘To change something / I will have to die.’

*

During summer 2013, people around me began to feel what I had felt two years earlier when I moved to Kyiv. It was then that I first saw a kind of fear in the eyes of even the most optimistic businessman I knew. He told me that his colleagues were really anxious: ‘No one is safe these days, even if you pay them.’ Paradoxically, after more than two years of being alert, I relaxed. Maybe it was just me: I was too tired, too disappointed with my personal life, way too absorbed by my job. Yanukovych kept declaring that Ukraine would sign the EU Association Agreement. As long as he did, there was still hope that ‘The Family’ would behave, hope for some sort of evolution. I no longer expected an uprising or saw the need to go underground. I bought nice coffee cups.

The uprising began anyway.

*

There are many reasons for a man to dislike his mother-in-law. My great-grandfather Ivan Ustinov had political ones. She was from the Catholic Polish nobility, and was described as an arrogant, authoritative woman who was filthy rich and managed her estate from her pillows. However, she was also said to be personally capable of loading a dray with crops to show workers how to do it, since no one did things right. He was a leftist with Orthodox, Ukrainian and Russian roots, an engineer, educated and not exactly poor, though he had no title. She disapproved of her daughter’s choice and so did the family. My great-grandmother was excluded.

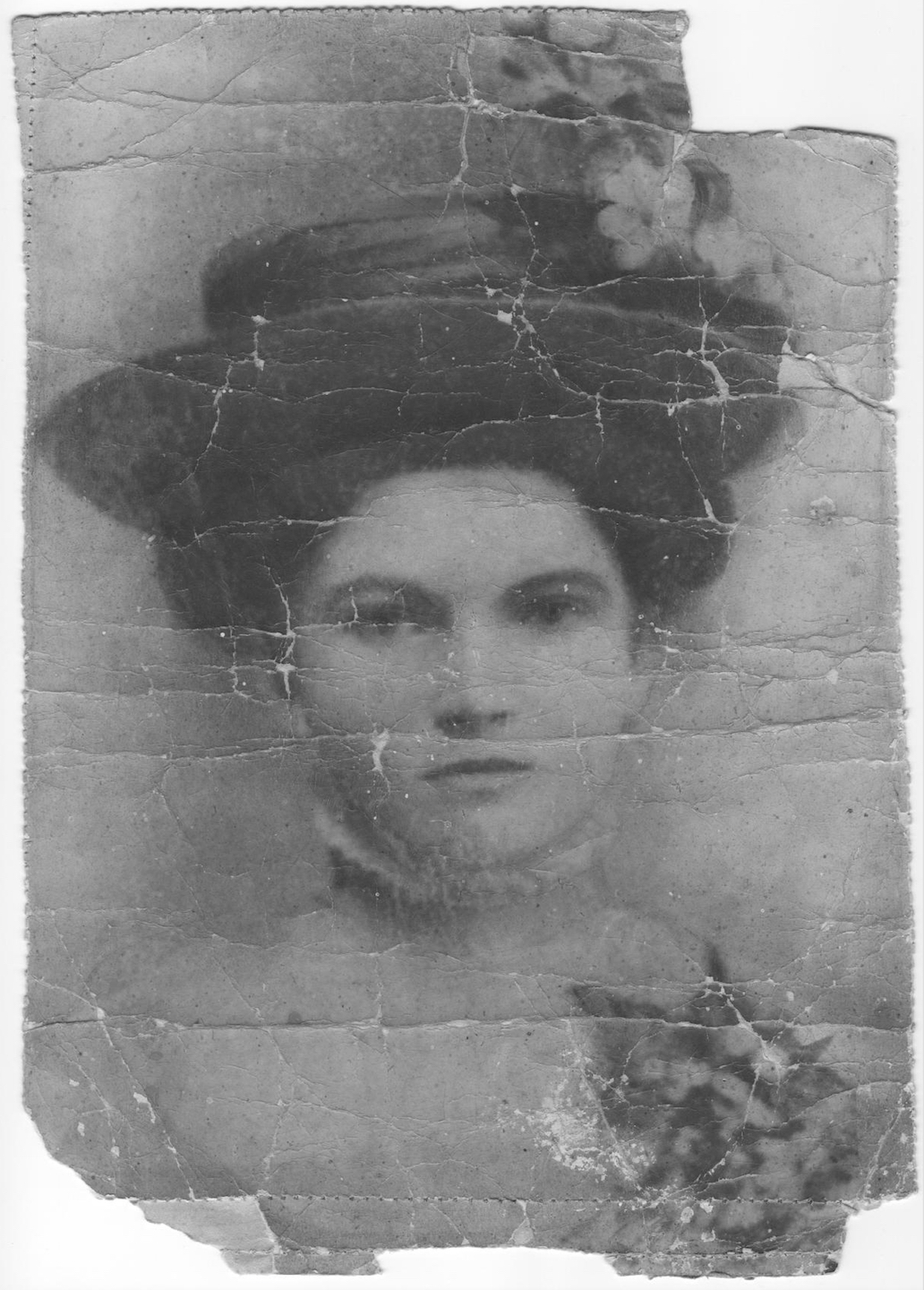

This is all I know about my great-grandmother’s family. My grandmother told us that her mother, whose name was Maria, died of tuberculosis in 1925 when she was very young, after they left for Evpatoria (Crimea) in search of a better climate. When we asked about her mother’s family name, she claimed to have forgotten it. All she had left of her mother were two photos: a 1910 portrait and a family photo of her while pregnant with my grandma. A reproduction of the portrait still hangs in my parents’ home. The contrast between the two images shows how hard those years of war and revolution had been, during which she led an unsettled life bringing up three children.

Maria. Private collection.

It looks very much like her family name was a well-kept secret, that my grandmother didn’t just ‘forget’ it. She and her siblings (or was it Ivan Ustinov?) burned all their birth certificates, and it was only shortly before her death that we learned that grandma was born in 1918, not in 1922 as she used to claim. According to family legend, my great-grandfather told his children that they would be better off never knowing who they were.

At the end of 2014, after almost four years in Kyiv, I realized I could inquire at the archive of SBU, the Security Service of Ukraine, inherited from the KGB-NKVD, about Ivan Ustinov’s criminal record and about that of his son Arkady (my grandma’s older brother). They were arrested in Kyiv in 1937. The simple idea that I could make an inquiry had never occurred to me before: it was their SBU and they controlled the archives. Now the city and the state were ours, I did not have to feel ashamed about entering the SBU office or filing an inquiry. It was just another service I received as a taxpayer.

My great-grandfather and Arkady had been accused of propagating ‘anarchist and anti-Communist ideas.’ The story is as banal for those years as it is tragic: like millions of other people who faced repression during the Stalin era, they became victims of an envious colleague who denounced them. What really struck me – beyond how emotionally draining it proved to be to read such documents – was that among all the records of interrogation, protocols, inquiries, third-party statements, even the hostile ones, no one said a word about Ivan Ustinov’s first wife Maria. Neither Ivan nor Arkady mentioned her name in the accounts they gave of their lives. Arkady mentioned only that she died in 1925 – as if the four children had popped up out of nowhere.

It was no family secret that Maria was Polish, though. Ironically enough, Ivan’s third wife (he had another one after Maria’s death) was also Polish and also called Maria. Actually, it was her apartment at the junction of Prorizna and Khreshchatyk Street that was blown up in 1941. It could well be that the family moved to her apartment after the arrest of Ivan and Arkady in 1937 and that, as a well-educated woman, she did most of the paperwork for their release. Practically homeless after the war, my great grandfather and his third wife Maria Cesarivna spent some time at my grandma’s place in the late 1950s in Lviv. My mother remembers Maria Cesarivna taking her to a mass in the Latin Cathedral (the Roman Catholic Church was permitted as a concession to the Polish minority) and buying her a bun afterwards. She holds dear Maria Cesarivna’s unconditional love, even though they weren’t actually relatives and Ivan, her husband, was no fan of my grandpa, a Red Army officer.

The Poles were a majority in Lviv before World War II. Most who survived the war had to move to Poland, usually to Wroclaw. Those who stayed constituted a minority in a city occupied by the Soviets (first in 1939 and then again from 1944 onwards). Lviv is close to the Polish border and it is almost the norm for people there to speak or to at least understand some Polish. Not for my grandma though. I never heard her speaking Polish and she was very vocal about her dislike of the language.

Anti-Polish and anti-Catholic sentiments were embedded in the Soviet school curriculum due to the general anti-western ideology. (Later I wondered how that ideology, formally atheist, could accommodate so much praise for the Orthodox Church.) But many Ukrainians also had good reasons to object to Poles, who had formed the colonial power and the ruling class. But I would say my grandma’s anti-Polish sentiments were quite unconventional. When my great-grandmother’s family was about to flee to Poland, my great-grandfather Ivan Ustinov begged them to take the children with them. They refused. Ukraine was torn apart by civil war and the Bolshevik invasion. Ivan stayed with the little children. Very soon the window of opportunity for him to leave shut along with the Soviet borders. The Iron Curtain fell and they remained there for the rest of their lives. My grandma never went abroad.

I know this story only because my grandma explained both her father’s and her own resentment of Poles. The Poles were distant, unknown relatives who abandoned her, leaving her to a life of hardship. This story was definitely not the central one she told us, I’m not even sure I heard it more than once. However, I have a mental image of my great grandfather and his shame in the midst of what was becoming hell on Earth.

When my parents were born, and when I was born myself, things were not that harsh. But I had inherited certain fears. One of them was especially acute in late November 2013: what if they abandon us again?

This is a very central and eastern European fear. It’s the fear the Hungarians felt in 1956. It’s the fear of the Czechs and Slovaks in 1968, and of the Poles in 1980. It was my fear then. What if they abandon us? What if we remain under Russian occupation forever?

Ironically, my contact with Poles and with Poland had never been so intense in Lviv as it was in Kyiv. This was mostly thanks to the Polish Institute and its support for Krytyka, the journal I worked at. The director of the Institute in Kyiv, Jaroslaw Godun, and especially his deputy Anna Lazar, did an outstanding job of supporting Ukrainian art, literature and publishing. She and Jaroslaw were also very helpful during Maidan, and I suspect they sometimes risked their careers (and more) for us.

Anna and Jaroslaw left Kyiv for the next city as planned in summer 2014. However, it felt like the end of an era. Some friends are irreplaceable.

*

At the end of October 2013, the last men and women left standing after the opening of conference ended up in the Buddha Bar on Khreshchatyk. These European editors and writers, my colleagues, were slightly disconcerted by the beauties dancing on the tables in bikinis, and the beauties with a few more clothes on at the bar, as well as the numerous free-and-easy foreigners who encouraged all that. The Swedish editor Carl Henrik Fredriksson and I took a break from the loud music and naked butts and stepped outside.

Carl Henrik is the most eastern European of all western Europeans I know (a compliment), the kind of sensitive, tasteful and wise gentleman who has a genuine interest in the world and who is immune to indoctrination. He asked me about my new novel and I answered I didn’t know if I could write it, because you need to have answers to write a novel, and I only had questions. What actually shapes our way of seeing, what is it that gives us the same sense of intuition about the way the world works? Taste, poverty, the Dynasty series that our grandmas used to watch spellbound in early 1990s? Can we, for example, really be close to people who cannot share our specific local experiences and who will never be able to share, say, the memory of a specific smell?

Actually, back then I had already written part of a new novel: ‘Already on the other side, at the beginning of autumn, at the end of the season, your memory blank, empty inside, you indifferently observe how the air cools down and odours return. For example, the incidental return of the smell of a canteen and washed floors from your childhood: only washed floors in schools, and perhaps occasionally universities in the post-Soviet world, smell like this. It is the odour of sour old rags combined with smells form a canteen: moist pastry, the butter on kasha, paint (specifically that used in post-Soviet canteens I guess). This “school smell” is, among other things, what unites us, it is what stands between us and people from other countries, like those sitting next to me on the plane. Can you fall in love with someone who doesn’t have this smell under his skin? Who are we without this mix of experiences?’

That’s roughly what I was trying to explain to Carl Henrik. That’s what I didn’t know and, therefore, why I didn’t have a new novel.

Carl Henrik looked towards the dark European Square and said: ‘If it’s good literature then, no, such closure is impossible.’

It was three in the morning. Khreshchatyk was silent and somehow sterile. The most dangerous people for a mile around were the bouncers at the Buddha Bar. Inside a journalist from a Catholic periodical was dancing on the table, and the joyful guests of our capital city put money in his pants; we missed all the fun.

One month later, Maidan would begin on this street. Sometimes life resembles good literature.

Some moments felt like a final chapter in a long old-fashioned epic novel, when all the main characters, your classmates and friends, people who’ve been so important to you for many years, or were so important many years ago, people you loved, and people who loved you, people who you owe so much, people who have grown old, all of them gather in one place for a resolution. When unbelievable things happen incredibly fast, and your sophomore love tries to put his flak jacket on you, and the whole world is looking.

I never wrote my second novel. Even if I could somehow cope with what we had just experienced and put my notes together, who would believe that I already had the plot before Maidan? And who needed a novel like this after what happened?

I remember the moment when I knew I had failed. It was during one of the night battles on Hrushevsky Street in January 2014. The fires and explosions had already broken out, the first fatalities and kidnappings had occurred, there were thugs on the streets. In the dark amidst the rubble, I saw the gearwheels of history being turned with bare hands, and scraping. I realized that I could have missed this very moment by being in other city, or in another country, having taken a slightly different turn in life or having made a different choice somewhere along the line. That thought was far scarier than anything else, a moment of genuine transcendental horror. And I realized I could never write anything so grand or even imagine it, I wouldn’t dare.

I had failed as a writer. We had won as citizens. A new life began.

*

My grandma died in 1999. She was in much pain during her last days and on morphine almost all the time. A Russian-speaker for as long as I could remember, at some point during her medicated last hours she began to sing in Ukrainian, something she had never done before. It seemed she had returned to the language of her childhood.

And yet, with the benefit of hindsight, there was something audacious about it. Fifteen years later, I saw people start to sing in moments of the greatest danger. That’s what we do here: we sing in Ukrainian when facing death.

I wonder how my grandma would like this new Kyiv. Having survived the air raids during World War II, she would certainly be terrified of me living in a city with the ‘bomb shelter’ signs that appeared in the summer of 2014, when we expected anything and everything, including an attack by Russia. Still, based on what I learned from my great-grandfather’s NKVD records, they would both be happy for me too, living in a Kyiv they never experienced: a bizarre, free city.

I cannot say I miss the days of Maidan. They were dominated by uncertainty and sleep deprivation, I felt useless and inadequate almost all of the time, constantly worried for my friends. Days of mourning followed. It was normal to go out onto the streets and not know when you would come back, you stopped planning anything more than a day ahead. When it ended, I struggled for some time to get back on track, to return to organized life. Yet I do miss that space.

It was also a time when my mental image of the city changed profoundly. During those days of revolution I tended not to take the subway home from the office on Khmelnystsky Street but walk to the crossroads with Khreshchatyk, where the first barricade was. The traffic stopped there, at the border between the ‘normal’ city and Maidan. There you first met the Maidan guards, mostly guys in balaclavas. You didn’t get stopped, at least I never experienced that. You couldn’t drive in, but everybody was free to enter on foot. I felt obliged to look the guards in the eyes though. I was surprised at how quickly I learned to make meaningful eye contact with total strangers, as if to say, ‘I’m here for the same reason as you’ or ‘Thank you!’ I would never have imagined I could learn anything like that.

Then I would walk down Khreshchatyk to the Maidan. The next barricade was on a side street – Prorizna, where my grandma had lived, and where her father and Maria Cesarivna had worked on the building site where the Central Post Office (Dom Svyazi) was then being constructed. This building too was blown up in 1941.

Anna Lazar and her husband lived on the other side of Khreshchatyk. Though they did not say so in public, I knew they opened the doors to their place as a shelter at the most critical moments. I remember having dinner at Anna’s just a few days after power changed hands. Yanukovych had gone for good, but people were still on the street. There was no total relief or euphoria, it was strange. Looking back, I think maybe we just felt that it was a unique moment, the first and probably the last time we would see this street in such circumstances.

The next barricade was close to the current National Post Office building and the Maidan. Sometimes I took a subway from there, if the trains were running. Other days I stayed for some time. If it was late, I would walk home.

The location of the barricades on the east side of the Maidan changed in response to attacks by the Berkut, but most of the time the eastern barricade was near the Trade Unions building (which was set on fire in February 2014). It was another minute to European Square: uphill from there is Hrushevsky Street, which became a battlefield on 19 January 2014. I would then descend for another seven to ten minutes along Volodymyrsky to my district, Podil. Though the neighbourhood had not been dangerous before Maidan, I never used to go back that way before then. Yet I still felt perfectly safe, even at 3 a.m. all by myself. That changed when the titushki thugs (who were also real criminals) were brought to Kyiv after 20 January and started to attack people in the neighbouring areas.

In Podil, it was as if nothing had happened. Life continued as usual, cafes and restaurants remained open, nicely dressed people went about their business. In fact, this wasn’t quite true. My apartment faced the headquarters of the pro-Yanukovych Communist Party of Ukraine. The red flag was usually the first thing I saw upon waking up in the morning. (At a house-warming party in 2011, my friends joked that my balcony would be useful to a sniper; back then, sniper jokes were acceptable). At the beginning of December 2013, the Berkut had occupied the headquarters. When leaving home for the Maidan at night, I saw them changing shifts on the neighbouring yard. Soon they had a sentinel or two outside 24/7. I made eye contact with them too, hoping that they would feel my disgust.

The barricades remained in place until summer 2014, but by then the crowd there had become quite strange. It had all but turned into a tourist attraction. And, indeed, the tourists came in droves. Kyiv had become the place to be. In fact, everybody came: journalists, intellectuals, Joe Biden… It was not unusual to bump into someone there like Thomas Friedman of The New York Times. I changed my route and tried to avoid the Maidan, mostly because I wanted to remember the one I knew: tough, frozen, smoky, real. A place where I felt safer than ever.

Kyiv has changed a lot since. The armies of luxury cars may still shock, but there are many more affordable trendy places, and it is sometimes flatteringly described as ‘a new Berlin’ in the western media. Global brands and musicians film their ads and videos in Kyiv, it’s vibrant, it’s about start-ups and fashion, it’s ‘poor but sexy’.

To this day I retain a mental map of the city centre with the barricades where, oddly, I still feel safest. I’m not sure this will ever change – even after political opportunists have repeatedly profaned the actual space and its symbols. Reading the news, I think we still need to keep the barricades in mind (though the last thing I would wish for is ‘the new Maidan’). Perhaps I don’t miss the barricades themselves so much as the clarity they provided, and the inevitable moral choice they ultimately demanded.

I’m especially grateful to my friends who brought their small children to Maidan. Those children will remember neither our faces nor our conversations from those days, but I know they will remember the smell, the smell of smoke in the frozen air.

Published 17 September 2018

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Oksana Forostyna / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Russia’s orbit

Osteuropa 4/2024

Repression, murder, war: on the logic driving the Putin regime toward ever-greater excesses of violence. Featuring Yuri Andrukhovych on the Russian colonial empire – the only ever to have tried to reconquer a former possession. Also: articles on Navalny, and on what next for Georgia?

The difference between knowing from distance that war is being waged and living that reality couldn’t be more extreme. But can awareness of multiple repercussions turn protective disassociation from violence into active solidarity? ‘The Most Documented War’ symposium in Lviv, Ukraine, provides valuable pointers regarding engagement and responsibility.