Belarus: Between a rock and a hard place

Something unbelievable is happening in Belarus: people, especially in the provinces, are protesting, despite their fear of political repressions. Meanwhile, in the urban centres, a pop-cultural movement has begun seeking a new Belarusian identity. Against the background of economic crisis and tensions with Russia, the regime is being forced to rethink its neo-Soviet cultural policy.

Belarusian president Aliaksandr Lukashenka is not known for surprises that knock your socks off, so to speak. But “Daddy” (bat’ka), as Belarusians refer to their autocratic president, has rarely been seen so emotional. On 3 February 2017 Lukashenka held a press conference that lasted a record seven-and-a-half hours. This one-man show touched on many topics, which Lukashenka expounded on with much hot air and pathos, without giving concrete answers to the questions posed to him. There was one subject, however, on which the president, who has ruled the republic of Belarus since 1994 with a decided tendency towards autocracy, was very specific: Russia.

Relations with this powerful neighbour and its president, Vladimir Putin, have always held great significance for Lukashenka’s autocracy. But now they are worsening at a worrying pace. Lukashenka gave a monologue that topped 30 minutes, complaining about the overinflated gas and oil prices that Russia is demanding from him. He accused Russia of violating international agreements: on 1 February 2017, the neighbouring state had put up undeclared border checkpoints on the Belarusian-Russian border in the areas around Smolensk, Pskov and Briansk. Up to that point, no border controls had existed.

Russia’s actions can be seen as a response to the relaxation of visa requirements decreed by the Belarusian president in early 2017. Citizens of 80 countries can now travel to Belarus for up to five days visa-free, although to take advantage of this they have to enter the country by plane via Minsk. This opening-up to the West could be a thorn in Putin’s side, since Russia has traditionally seen the territory of Belarus as a buffer between it and the EU and NATO.

Since Yeltsin’s presidency, Lukashenka has been a more or less reliable partner for Russia’s interests. Back in the ’90s, when the idea of a unified state was still on the table, rumours floated that Lukashenka was rather interested in becoming its president. The young Belarusian president, who embodied a strong desire for order, was a beacon of hope for conservative politicians in crisis-wracked Russia. With Putin, and with Russia becoming economically and politically stronger, the picture has changed. Lukashenka’s regime is economically and financially dependent on Putin – and thus also on the political discretion of the Russian government.

It was probably because of this that, at the end of his speech, Lukashenka spoke forcefully in defence of Belarus’s sovereignty: “If some smart alecs here think that Belarus is part of the Russian world or even Russia itself, forget it! If somebody says that historically there was never even a Belarusian state, my answer is: now there is one, and it should stay that way. We will not give our country away, not to anyone.”

Is Belarus’s sovereignty really in danger? The Russian annexation of Crimea, where there is a Russian-speaking majority as in Belarus, and the war that Russia is waging in eastern Ukraine seem to feed such fears from the Belarusian head of state. Lukashenka hinted at this at a meeting with academics in Minsk at the end of January 2017. “We got our independence very cheaply,” the head of state said. “Every nation needs to fight for it. Right now our brother Ukraine is fighting for its independence. We can’t afford to fight. We are a peace-loving nation.” A major military exercise known as “West 2017”, which Russia has planned for this summer with 100.000 troops on the territory of Belarus and Kaliningrad, has also been stoking speculation in Belarus for months about a possible occupation.

Tensions between Lukashenka and Putin, however, are nothing new. As early as the run-up to the 2010 Belarusian presidential elections, both sides engaged in a major media war, trying to damage the other’s image. Before that there had been plenty of so-called milk, meat, and gas wars between the two partners. Since 2015, however, relations between Belarus and Russia have deteriorated appreciably. This can be seen on several levels. Except for potash fertilizer, Belarus has no lucrative resources of its own. To date, Lukashenka’s regime has benefitted not only from comparatively affordable gas supplies from Russia, but also from cheap crude oil, which is refined in Belarus and then sold on to the EU. Last year, Russia delivered substantially less crude, and a further decrease has been announced for this year.

Additionally, Russia’s market plays an essential role for Belarus, with more than 40 per cent of all Belarusian exports going to its neighbour. But a ban has been imposed on certain goods from Belarus. Since 2011, the Belarusian economy, which is largely built upon unprofitable state enterprises, has been in decline. Lukashenka needs money and credit to maintain his regime and his hold on power – ideally money and credit that are not contingent on reforms or democratization, conditions that the IMF or the EU set.

In this regard, he clearly cannot expect any help from Putin at the moment. But tacking between Russia and the West (or the EU) is part of the practised survival strategy of “Europe’s last dictator”. More often than not, he has turned promises of reform made to the West in exchange for cash into rapprochement with Moscow. Lukashenka considers the question of state identity and nominal culture as a means and expression of this manoeuvring und bargaining. This has become ever clearer since the first clash with Russia over cheap gas prices in 2007.

Since the start of the war in Ukraine, Lukashenka has toned down his beloved neo-Sovietism and begun making overtures to Belarusian national culture. As a weak president in a worsening geopolitical and economic situation, the trump card Lukashenka is probably trying to play is a sovereign Belarus. It has also earned him the encouragement of some national politicians and intellectuals, who have been openly hostile to the president up until now.

Lukashenka is now also trying to present the Belarusian language as an instrument of demarcation and self-assertion. When he met with Iosif Seredich, the editor-in-chief of the opposition newspaper Narodnaia Volia (National Will), for a two-hour private audience on 13 February 2017, Lukashenka gave a television address in Belarusian, a language that he himself has demonized for many years as the language of the opposition and which has been repressed and marginalized. In light of the war in Ukraine, young Belarusians are demanding a greater turn towards their own national culture. In the future, Lukashenka could try to present himself even more strongly as the preserver of this culture and as guarantor of a sovereign Belarus. At least outwardly, the state and regime are already granting the Belarusian language more scope, even if it is still far from being seen as the equal of Russian.

On 20 January 2017, for example, a jury and television audience chose the first ever Belarusian-language song in the national selection process for the Eurovision Song Contest. The young duo NAVI will take part in the competition in Kyiv with their song “The History of My Life”. The Belarusian-language internet community saw this selection as a small victory for Belarusian. In late January 2017, a former police officer in the Gomel region was fined because he had insulted Belarusian as “a putrid and decaying corpse”: also a first for Belarus. These two events prompted the newspaper Nasha Niva (Our Land), founded in 1905, to publish a cover bearing the title “A soft Belarusianization” at the end of January.

The combination of a weighty geopolitical conflict in the neighbourhood and tensions with Russia is clearly driving the rise of a nationally-oriented culture. In what follows, this development is analysed further.

Early signs

On 20 January 2015 Lukashenka surprised those who saw him as a repressor and enemy of Belarusian culture and identity. At the 42nd Congress of the Belarusian Republican Youth Union (BRSM), which critics call “Lukamol” in allusion to the Soviet Komsomol, the then sixty-year-old president said, “Culture is what makes a Belarusian Belarusian, rather than just some ‘local’ who leaves no trace on that speck of land where he happens to be.” He alluded to Belarus’s rich heritage – not only literature, music or architecture, “but also the language that we are beholden to know; the history that we are beholden to remember; and the values that we must respect”.

That Lukashenka gave his message in Russian and not Belarusian was likely because his audience – BRSM members – barely know the language. After all, in their loyalty to the regime, they have only done what Lukashenka has hammered into them for years: not to learn or speak the “language of the opposition” and instead to pay homage to an anaemic Soviet cult – in the language of the Soviets, of course: Russian.

It is truly hard to imagine that belaruskaia mova is now becoming Lukashenka’s new darling. So what has happened to make the neo-Soviet president consider Belarusian to be on par with Russian? It is plain to see that the war between Russia and Ukraine that has been keeping Europe on tenterhooks since 2014 is one reason for Lukashenka’s alleged change of heart. After all, this conflict, which is fuelled by Russia through material support and propaganda, has shown Lukashenka the fragility not only of Belarusian sovereignty but also of his own position on Russia’s doorstep.

In Russian nationalist blogs such as “Sputnik and Pogrom”, the western neighbour is portrayed as a historical part of Russia. Countless Russian nationalist websites demand the occupation of the “Northwest Territory” – a designation that dates from the era when Belarus was part of the Russian Empire. Since the end of 2014, moreover, Russian state media outlets and analysis sites also seem to be zeroing in on Lukashenka. For example, in mid-December the Russian channel REN TV aired a story that claimed that the West was planning a putsch in Belarus. With this not only the opposition but also Lukashenka got their just desserts.

Recognising the potential danger, in 2014 Lukashenka played the game that he’s best at. He tacked between offers of partnership and dialogue with the new Ukrainian government and the EU on the one hand, and a mix of cautious criticism, concessions and avowals of loyalty to Russia on the other. He established Minsk as the site of negotiations for Ukraine and the separatists, in order to win himself respect and bargaining space. The EU rewarded this by announcing in February 2016 that it would let sanctions against the Belarusian regime expire. An open conflict with Putin, as Lukashenka well knows, is not something he can withstand. Militarily, Belarus is at the mercy of its neighbour.

So does Lukashenka see culture and language as an opportunity to turn his back on Russia? A look at history is useful here.

The Belarusian language has always existed in the shadow of other cultures. The Belarusian national movement, which emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century, had a tough go of it in the repressive Russian Empire. In the Soviet Union, after a short period of flourishing in the 1920s, Belarusian was relegated to the status of a folklore museum piece while Russian dominated as the lingua franca. It was only with the era of perestroika and glasnost that a national movement began to resurface; like its predecessor at the turn of the twentieth century, it dreamed of a “Belarusian renaissance”. The Belarusianization that followed independence in 1991 made many Belarusians fearful, however. After all, the majority of Belarusians speak Russian in their everyday life. What’s more, in the early 1990s many held primarily positive feelings towards the Soviet Union, since the quality of life and education levels had been comparatively high in Soviet times.

The election of Lukashenka in 1994 was a product of this nostalgia. As early as 1995, with the help of a controversial referendum, Lukashenka brought Russian back as the state language. What remained from the short period of Belarusianization between 1991 and 1994 were street names and bureaucratic forms in Belarusian, which were not always understood by officials themselves. Belarusian is an official language only formally; in practice, the language struggles to maintain even a marginal role under Lukashenka. Most state television and radio programs are in Russian. Between 1990 and 2005, the total circulation of publications in Belarusian fell from 9.3 to 2.9 million copies annually. Authors who write in Belarusian reach only a very small audience.

To date it is impossible to receive a complete school education in Belarusian. In Minsk there are a mere five Belarusian-language secondary schools. In the 2012–2013 school year, out of 909,000 schoolchildren across the entire country, only 150,000 took classes in Belarusian, mostly in rural regions. According to various surveys, between three to twenty percent of the population speaks Belarusian (although people may be wary of admitting to it). At the same time, almost everyone born in Belarus understands the language easily. Belarusians are thus more or less bilingual or trilingual: there is also a mixed language, known as trasianka (literally meaning low quality mixed hay), that has developed out of Belarusian and Russian. It is mainly spoken in rural regions. But Russians can have problems with the Belarusian lexicon, since it has a large number of words that come from Polish or Yiddish.

Lukashenka’s aversion to Belarusian

Lukashenka is a man of the Soviet Union, who comes from the east of the country and worked as the director of a collective farm. He speaks Russian and, since 1994, has turned Belarus into a miniature version of the Soviet Union, where to this day there are collective farms and the KGB. He built up the security and secret services, while isolating and battling the opposition and dissenters. In the 1990s, Lukashenka demonized the Belarusian language as the language of the “fascists”, because during the Nazi occupation Belarusian nationalists collaborated with the Germans. In the 1995 referendum, the president got fitting state symbols for his Soviet style of rule. Instead of the Pahonia coat of arms and the white–red–white flag – both symbols that harken back to the time of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania – adopted in 1991, he introduced a modified version of the coat of arms of the Belarusian SSR, as well as the colours of the Soviet republic: red and green.

This revival of Soviet symbols, as well as his anti-Belarusian politics, brought Lukashenka not only the approval of the majority of the electorate, but also brownie points with Russia. In April 1996, he and Boris Yeltsin signed an agreement on the creation of a union state. By 1995 Lukashenka was asserting loudly that there were only two major languages: English and Russian. “Nothing big can be accomplished in Belarusian.” Many Belarusians concur with his verdict to this day – it is the same thing that has been drummed into them for centuries by the Russian Empire, the Soviets, and now Lukashenka: Belarusian is a substandard dialect spoken by peasants. In this telling, Belarusians as an ethnic group are merely a branch of “the great Russian nation”. The Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich said in an interview with the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in 2013 that she saw the Belarusian language as “immature” and a “peasant” language. This characterization (later retracted) by an author who writes in Russian triggered a chorus of outrage from Belarusian speakers. Not only because it was a foolish thing to say, but because it hurt many Belarusians, who already have a crushing inferiority complex.

Alternative identities

In his policies, Lukashenka has long favoured a neo-Soviet conception of history and identity, along with a corresponding autocratic system. The Russian language was an expression of this. In contrast, Belarusian was equated in his mind with an orientation towards the West and its democratic values, as promoted by the national-democratic opposition. For some Belarusians, even in the twenty-first century, the choice of language – Russian or Belarusian – is one between different models of identity, history and politics. Democracy or dictatorship? West or East? The Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Rzeczpospolita or the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union?

Many nationally-inclined Belarusians dreamed in the 1990s that their children would become Belarusian speakers and began to raise them accordingly. Today many of these children speak Russian in their daily lives – simply because life mainly takes place in Russian. If someone decides to use Belarusian as their everyday language, they have to go to great pains to do so and be prepared to meet resistance. They often feel exotic, like foreigners in their own country. Lavon Volski, the charismatic lead singer of the punk rock band N.R.M. and icon of the Belarusian-language music scene, sang about this phenomenon in his song “Chuzhy” (“Foreign”).

Nonetheless, in the early 1990s a new generation of young musicians and literati arose that was inspired by by the national-romantic dreams of their parents and their opposition towards the Soviet regime. This generation sought alternative identity models: for them, the Belarusian language offered an alternative conception of history, in which Soviet era was subordinated to that of the pre-Russian Empire. Naturally this also led from time to time to a nationalistic conception of history and a new set of myths.

Punk rock bands like N.R.M., which was critical of the autocracy of President Lukashenka from early on, managed to popularize Belarusian and make it appealing to young people. The generation that grew up in the ’90s listening to its anthems is to this day referred to as “Generation N.R.M.” Nezalezhnaya Respublika Mroya, or the “Independent Republic of Dreams”, became a melting pot for young people who opposed the re-Sovietization of the country and who resisted a society that was marching backwards into the Soviet Union and denying them self-fulfilment. Since then, Belarusian as expression of an alternative cultural code has existed in an urban parallel world that is largely regulated by the regime. Herer, despite all the adversity and resistance from the system, the Belarusian language could serve as a cultural marker of difference and opposition.

Gradual de-stigmatization

The cultural power that the Belarusian language took on in the ’90s also produced a new generation of writers, artists and publishers. In the 2000s, Belarusian blossomed as the language of culture and became a hip alternative to the “official cultural system”. This was possible because the regime backed off from the demonization of Belarusian at that very moment. Constant conflicts with Russia over cheap gas and credit forced the regime to look for a new identity model – a model that would also henceforth ensure Belarusians’ loyalty to “Daddy”. Soviet nostalgics, who at that time had been the President’s main power base, were dying out, and a new generation was emerging that came of age in an independent Belarus and had no memory of the Soviet Union. This generation could hardly be inspired by the mythology of partisans in World War II, by Victory Day parades, or by Soviet cult. In order to ensure its survival, the regime, which is in any case very technocratic, needed a new, attractive cultural model that would work in the long term.

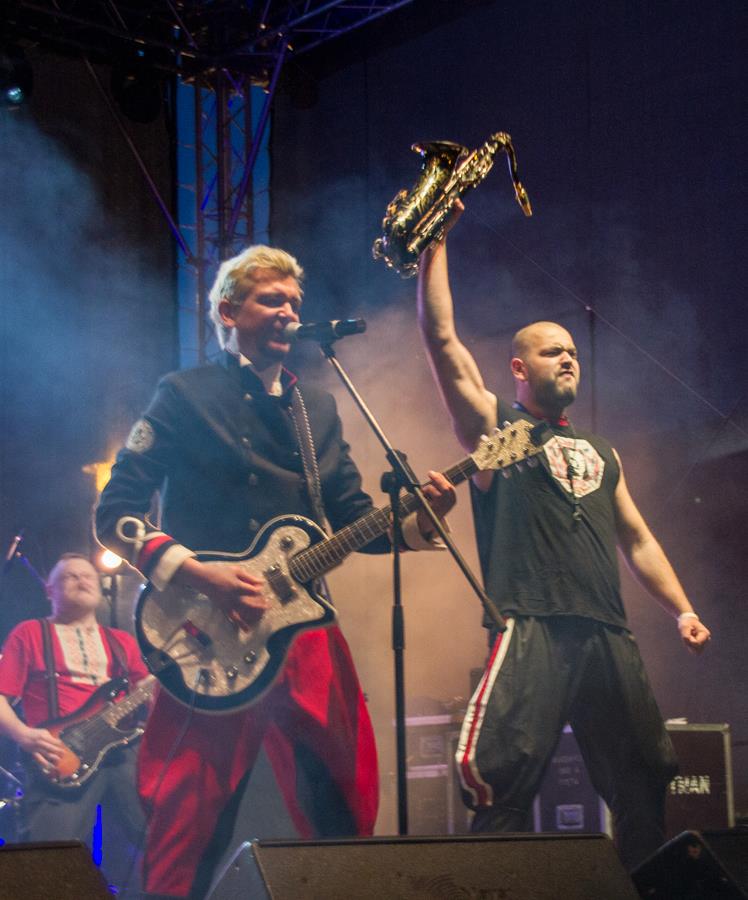

Krambambulya, one of the projects of Lavon Volski (left); on the right is Pavel Arakelian. Copyright: Krambambulya.

Younger Belarusian urban dwellers are more pragmatic when it comes to switching from Russian to Belarusian or vice versa. Sergei Mikhalok, who enjoyed great success with his band Lyapis Trubetskoi throughout the entire Russian-speaking world, certainly contributed to this development. The band came from Minsk and up to 2007 mainly played ironic, clownish rock and pop songs in Russian. With the 2008 album “Manifest”, Mikhalok turned towards pugnacious Belarusian-language agitprop, without entirely renouncing Russian as a means of artistic expression. With his new band Brutto, which is banned in Russia and until recently in Belarus too, Mikhalok is going the way of more politicized texts, which he performs in Russian and Belarusian and which deal with a turn to a unique national culture. Today, speaking Belarusian has scarcely any association with stereotypes such as “dissident” (3.7 per cent) or “nationalist” (2.3 per cent).1 Additional surveys repeatedly confirm that Belarusians see both Belarusian and Russian as an expression of their culture and history.

New initiatives

Aside from the entrenched political battles, since 2014 Belarusian has in fact been experiencing a mini-boom. Initiatives like “Mova Nanova” (“Language Anew”) or “Mova tsi Kava?” (“Language or Coffee?”) enjoy great popularity throughout the country. These free events are not simply language courses, but also educational and informational programs, where famous Belarusian-speaking intellectuals, writers or musicians appear and which convey a western historical narrative and cultural model for Belarus. Mova tsi Kava? was founded in 2012 by, among others, the young television journalist Katsia Kibalchych. In early 2014, the journalist Hleb Labadsenka broke off due to creative differences and, together with the philologist Alesia Litvinouskaia, founded Mova Nanova. This project even managed to obtain state registration as an “educational institution” on 27 November 2014.

In addition to these courses, projects run by “Budzma Belarusami!” have also grown in popularity. The cultural organization has existed since 2008 and has led the way in promoting Belarusian language and culture. Budzma puts on concerts, holds design and writing competitions, and publishes well-produced books and videos on Belarusian history; the target audience is primarily young Belarusians. Additionally, well-known authors like Viktor Martinovich or Alhierd Baharevich have columns on the Buzdma website.

Belarusian culture’s newfound popularity has also found other outlets: traditional embroidery motifs (“vyshyvanki”) have sparked a real fashion trend, which is reflected in designs for t-shirts, blouses or underwear. Since 2016, these national motifs have even adorned the uniforms of the Belarusian national football team. There have been festivals and parties dedicated to Belarusian, and various initiatives have arisen to demand that the title of the Russian Wikipedia page for the country be changed from “Belorussia” to “Belarus”. On 9 October 2014, during a football match between Belarus and Ukraine, fans of both teams united to sing songs in support of their countries and against Vladimir Putin. The Belarusians waved banners with unofficial national symbols, like the Pahonia coat of arms and the white-red-white flag. All of this took place against the backdrop of the annexation of Crimea and the military conflict in Ukraine, which drove young Belarusians to separate themselves more strongly from the russkii mir and to identify more closely with Belarusian.

Reorientation versus repression

It seems that Lukashenka is trying to use these circumstances and Belarusians’ fear of a similar conflict in their own country to his own domestic political advantage, to set a retreat from his lovingly cultivated neo-Soviet cultural model in motion. When the government was restructured in December 2014, Lukashenka named Aliaksandr Kosinets head of the powerful presidential administration. Before that, the erudite surgeon had been governor of the region of Vitebsk, where he had overseen the erection of the first monument to the Lithuanian Grand Duke Alhierd (1345–1377) on the territory of Belarus. This was a monument that certainly did not fit with Lukashenka’s traditional neo-Soviet myth-building. And on 31 December 2014, for the first time since 1994, Belarusian state television did not show the Russian president’s New Year’s speech.

But does this really imply an about-face and a turn towards Belarusian national culture? Not in the near future. After all, this would give greater opportunities to the nationalists, whom Lukashenka has spent his entire tenure fighting. The result would be a stronger creative culture scene, which the president could scarcely hope to control, given the cultural weakness of his own system.

That the regime doesn’t want to allow this is demonstrated, for example, by the closure of Ihar Lohvinau’s publishing house in 2013, after it had developed into the linchpin of the vibrant alternative literary and cultural world in Belarus. Lohvinau’s bookstore in Minsk, which had established itself as a home for the Belarusian-speaking cultural world over the previous seven years, was slapped with a fine of around 58,000 Euros in January 2015. The official reason: Lohvinau had no official license to run a bookstore. He had applied for one from the Ministry of Information six times in 2014. Each time his application had been denied on specious grounds. The real reason for the fine is obvious: he is someone who advocates for freedom for art and culture.

So more freedoms should not be expected under Lukashenka in the near future. His ongoing repressive policies, which are also directed at particular musicians and writers, will prevent him from having substantially greater room for manoeuvre in the West. At the same time, the regime is unwilling to leave Belarusian to the “Belarusian ghetto” (as writer and artist Artur Klinau put it) alone, but seeks to “play along” with this sphere and to gain influence over the increasingly popular Belarusian cultural model.

Forecast: Way out or dead end?

Lukashenka is a strategic actor who is forced by his own weak position to constantly try to create new opportunities and room for manoeuvre. So what options may emerge for the president from the current situation? Overwhelming support from the Belarusian population could help the president to strengthen his own position vis-à-vis Putin’s Russia. Lukashenka is therefore anxious to secure his image as the defender of an independent Belarusian state (even if he was the one who pushed and protected Russian influence in his own country for years, to secure his own power). He is portraying himself as ready for dialogue with people that he had long classified as “oppositional” and “nationalist”.

Moreover, he is trying to introduce Belarusian culture as a powerful instrument of demarcation and self-assertion. This is meant to signal to Putin that Lukashenka is in principle prepared to part from the “Russian world” and its “imperial” stranglehold. An “implied” Belarusianization that is still not fully launched could in turn become a trump card in a political power game with Putin: namely as a bargaining chip for loyalty to Russia, loyalty that would be rewarded with further loans and gas supplies.

In this case, Lukashenka would by and large maintain the dominance of Russian cultural influence in Belarus. He would hold firm to his system’s neo-Soviet façade and prevent any of Belarus’s 65 remaining Lenin statues from being torn down – which would please someone with as much Soviet nostalgia as Putin. At the same time, he must also make concessions to people in his own country who want to adopt a unique Belarusian identity after the war in Ukraine. This search for a new state identity makes the situation even more difficult for Lukashenka.

At the moment, it does not look like Lukashenka’s tactics will succeed. On the contrary: Putin seems to be gradually losing patience with the capricious president – hence the erection of border checkpoints and waning financial support. In any case, Putin has the upper hand: if it comes to an open exchange of blows, Lukashenka cannot win. But the economic crisis at home is forcing him to act.

Belarusians are experts at suffering and enduring and for a long time have responded to the mounting economic crisis with stoic calm. On the one hand, this can be attributed to the war in Ukraine, which Belarusians perceive as a possible threat to their own country. On the other hand, they interpret their neighbour’s difficult reform process not as a straightforward sign of hope for the possibility of a better life, but even more so as chaos that they want to avoid in their own country at (almost) any price.

In February 2017, protests broke out, with up to 5000 people attending demonstrations on October Square in Minsk. In the days and weeks that followed, similar demonstrations took place in many other Belarusian cities. The trigger for the biggest protests since the December 2010 presidential elections was the so-called Decree Nr. 3. This law, referred to as a “parasite tax” in Soviet-speak, forces Belarusians who have been unemployed for more than six months in a year to pay an annual tax of around 180 USD. That’s a lot of money in a country in which the average salary is officially 380 USD, although the real figure is more likely to be between 100–120 USD.

Around 470,000 Belarusians are affected by this decree. Videos and photos from the protests show that the protesters are not the opposition’s usual clientele: on the whole, they are middle-aged men and women who fear for their very existence. During the protests, chants like “Go away, Lukashenka!” could be heard, and in interviews protesters say that they are dissatisfied with their own (and their country’s) economic situation and do not trust the authorities to resolve the crisis. For the time being, the repressive apparatus is holding back. But the regime is also making clear that it is unwilling to give the demonstrators more leeway. Since beginning of March, more than 260 demonstrators, activists, bloggers, journalists and a few well-known opposition politicians have been arrested and sentenced to prison or given fines through summary judgments.

That Belarusians, who have been described as politically apathetic, have summoned the courage to take to the streets shows how desperate they think their situation is. Under pressure from the protests, Lukashenka has suspended the detested tax. But the fact that the protests have not abated indicates that the tax was just an outlet for general dissatisfaction. The problem obviously lies deeper.

After more than twenty year, people are wary of Lukashenka. They want a new outlook. Experts and observers assume that it will not come to a Maidan, like in Ukraine. The political opposition is too small, too isolated, and too divided. And Belarusians themselves would hardly be prepared to push things to the limit, given the repressions that they would expect as a result. All in all, the protests are a further sign of the profound crisis that Lukashenka’s regime finds itself in.

Help could come from the West. But it is difficult to imagine that Lukashenka is anxious to move decisively in the direction of the EU and the West (who are too preoccupied with their own crises anyway). In the medium term, if the regime were to open up further, it would mean the end of Lukashenka’s power. Plus, such a step would be very likely to prompt Russian intervention. It is conceivable that Putin is letting the Belarusian president squirm until, in exchange for new loans, he agrees to tough compromise conditions. This would enable Russia to have the military base in Belarus that it has long wanted and would give the Kremlin even more influence over its neighbour’s economy – and thereby its politics as well. So, in Belarus, time is on Putin’s side.

The Belarusian president finds himself in the most difficult domestic and international political crisis of his time in office. The quandary Lukashenka has ended up in reflects once again Belarus’s tense position between East and West. The past has shown that the president is an expert at finding solutions that benefit him. But whether he can manage to do so in the near future is highly doubtful.

According to a 2014 survey by the cultural project Budzma Belarusami! (Let’s be Belarusians!); www.budzma.org

Published 22 March 2017

Original in German

Translated by

Kate Younger

First published by Eurozine

© Ingo Petz / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

'It’s important to be open'

A Knowledgeable Youth podcast

Remaining in a new country or returning home? The Knowledgeable Youth podcast delves into the complex decision-making refugees face when migrating, together with researcher Olena Yermakova.

The difference between knowing from distance that war is being waged and living that reality couldn’t be more extreme. But can awareness of multiple repercussions turn protective disassociation from violence into active solidarity? ‘The Most Documented War’ symposium in Lviv, Ukraine, provides valuable pointers regarding engagement and responsibility.